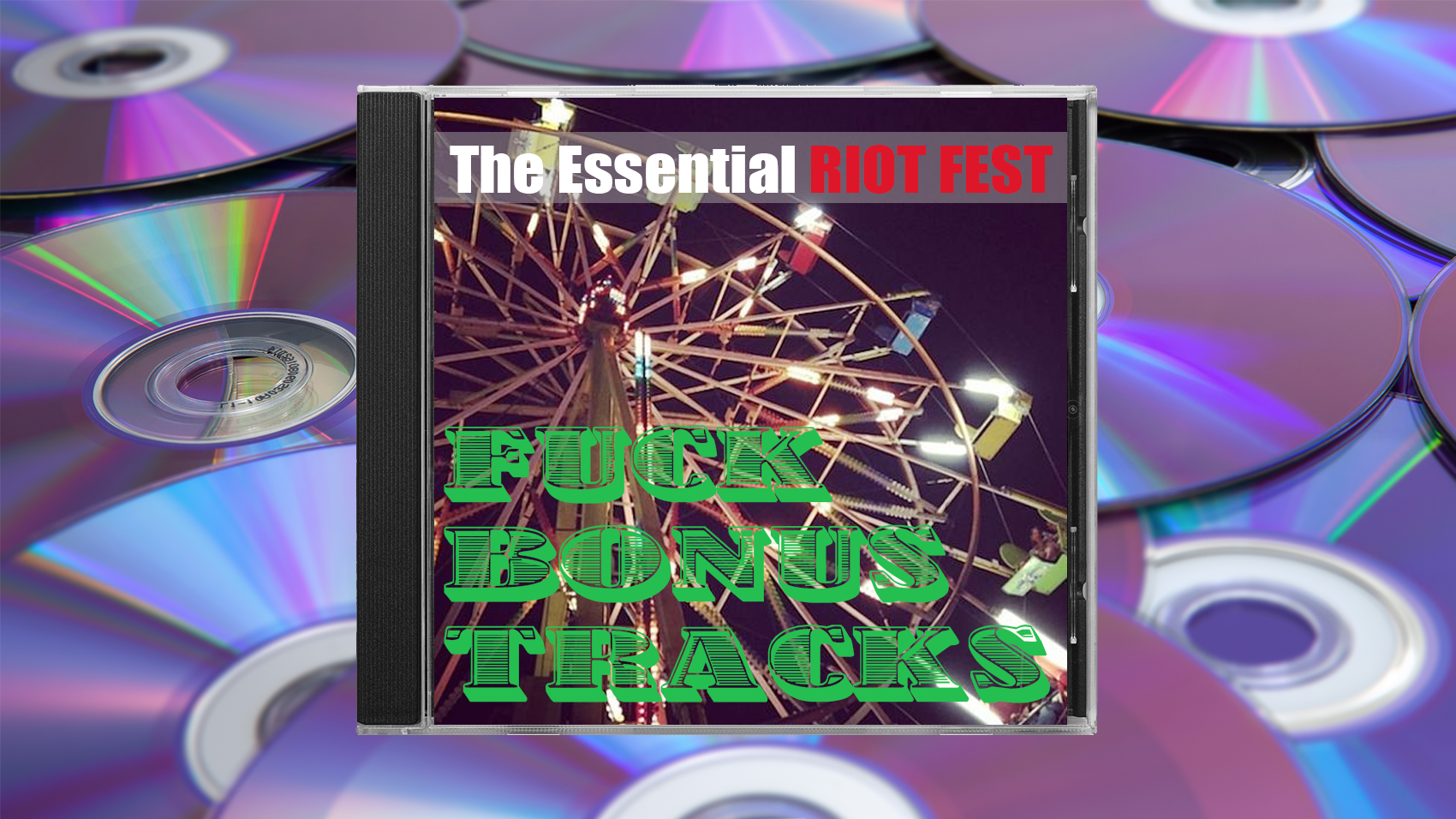

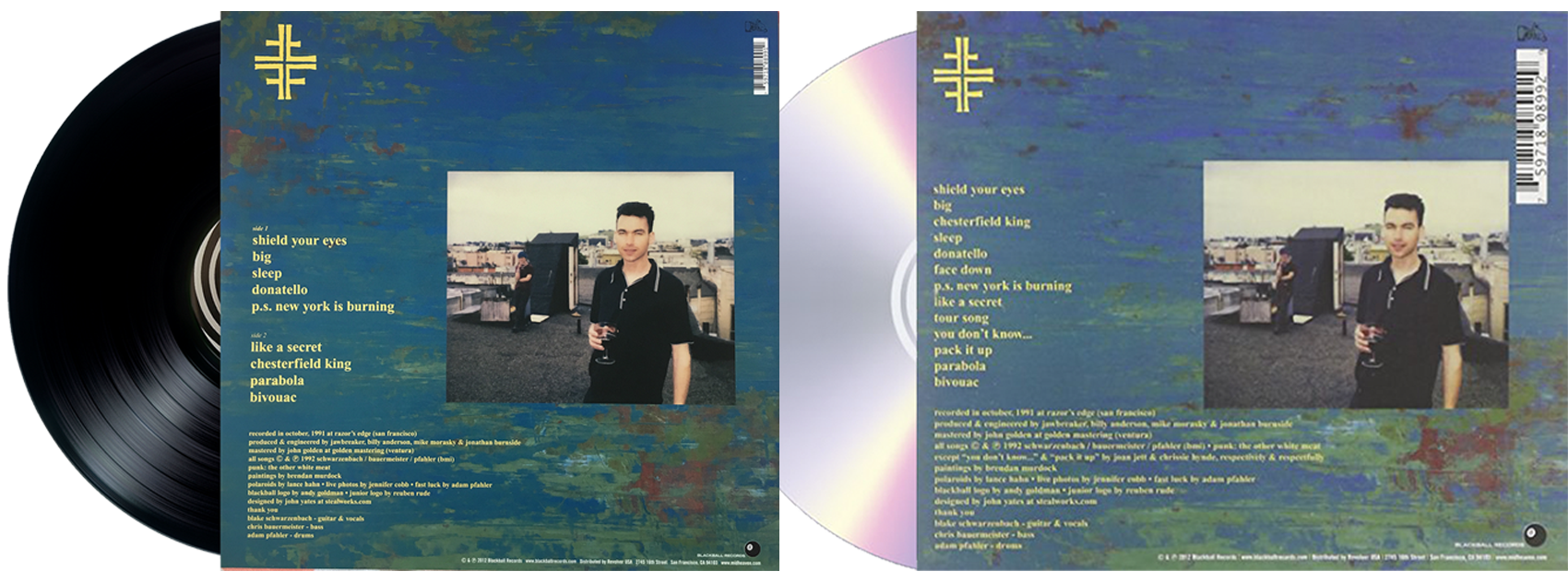

The first time I ever heard my favorite Jawbreaker record, I hated it—and it stayed that way for years. Having become a fan of the band through 24 Hour Revenge Therapy and Dear You, my first listen to that used CD copy of Bivouac had me incredibly excited…and then incredibly confused. The record felt overlong, lacking any coherent flow or discernable theme, with a pair of cover songs tossed into the back half for the sake of padding out the tracklist. It didn’t feel like a concise artistic statement from a band that, as I was quickly learning, was pretty good at that kind of thing.

When I finally found an LP version of Bivouac, I noticed a leaner tracklist and shorter runtime, and having long sold my CDs off I figured I’d grab the vinyl copy. That first spin unlocked something I didn’t know was there. Or more accurately, was there all along but had been kept hidden from me. It was then that I learned that the CD version of Bivouac added in the songs from the Chesterfield King EP, and although those are not without their merits, they handicap Bivouac in a way that, if anecdotal evidence is worth anything, remains a sticking point for a lot of people. What sounds confused and haphazard on CD is a bold, adventurous slab of punk when taken in its intended form. And while the Chesterfield King songs thrown in all willy-nilly is rather unconventional, it presages the craze of bonus tracks that would become pervasive over the next two decades.

“It’s pretty standard how you [insert bonus material], because you want to keep the integrity of the original releases,” says Kent Liu, the Vice President of Business Affairs at Rhino Entertainment, Warner Bros. Records’ archival label that’s done records by everyone from The Replacements to The Cure to the Grateful Dead. He notes that Jawbreaker’s Bivouac is a bit of an anomaly, and that, by and large, most releases take a standard form when having bonus material added. “The format kind of writes itself. If you’ve only got four demos, it’s gonna be a one-disc set. It’s the original album, then we tack on the four songs at the end. If there’s a live concert that could fill out a CD, that could be a disc by itself. If you’ve got more bonus tracks, that could be a third disc.”

Bivouac’s release in 1992 coincided with CDs becoming the dominant format for music. Similar shifts had been made throughout the history of recorded music: singles begat LPs begat 8-tracks and cassettes begat CDs. This onward march of technological advancement not only expanded the limits of how much music could fit on a given release, it also wildly improved profit margins for record labels. It’s why when CDs entered into the marketplace, labels rushed to reissue classic titles, boasting improved sound quality and, eventually, extra add-ons. Whereas vinyl records could fit, at most, 20 minutes of music on a side, a CD could hold a whopping 80 minutes. It only made sense that, the longer a CD was, the more inclined people would be to purchase it.

This development is what led many DIY punk and hardcore labels—ever the obstinate ones—to outright reject CDs on a fundamental level. Labels such as Gravity, Ebullition, and Slap A Ham (among countless others) would tout themselves as being vinyl-only, using this as a way of standing up for artistic expression over commerce. And as silly as it may seem now, it actually made a good bit of sense. For one, the ‘90s and early-2000s would usher in a windfall of deluxe expanded editions of classic albums. At a certain point, deluxe editions would begin to be released in tandem with new releases, making the standard album seem obsolete from the jump. Those limitations meant artists had to make tough decisions about what went on a record and what was kept in the vault. And while that kind of choice is never easy, it’s often necessary for creating a final product that can withstand the test of time.

Now, I know what you’re saying: How does this matter now, in the post-MP3 era of streaming music? Just look at what versions of albums are available on those streaming platforms. By and large, it’s some beefed-up version that turns a concise 10-track album into some sort of sprawling epic. Much like how bonus tracks were getting tacked onto CDs as a convincing reason for someone to repurchase something they already owned, this cunning maneuver on streaming platforms is an attempt to juice playcounts and get a few more pennies added to the royalty statement.

This is something that may seem like a minor inconvenience, or an argument championing an obsolete bias for a particular format, but what’s at stake is something bigger. It’s damaging our perception of the artwork itself. At once, fans are able to get a fuller picture of what went into making a record, hearing alternate takes, unused songs, and scraps of ideas that had long been lost. But at the exact same time, they are often presented in immediate succession to the original work. This means that the original album is rarely—if ever—taken on its face. Instead, people are thrown into headier, fans-only territory without having a say in the matter.

It’s something that can be seen on everything from reissues of David Bowie’s The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders From Mars, all the way down to albums that are being released in the here and now. Last week, when Vic Mensa streamed his hotly anticipated album The Autobiography on NPR a week before its release, the version found there already had two bonus tracks tacked onto it. Given that “We Could Be Free [feat. Ty Dolla $ign]” was a great closer, it felt like a tonal downshift to hear “Rage” just a second later—even if it’s a fantastic song in its own right.

Closing tracks are a special thing, and they are a big part of why an album can mean so much to people. Engaging with art requires a certain level of distance from it in order for the work to fully sink in. As Liu notes, this phenomenon is largely unique to the music world. “Nobody ever releases the rough draft of a novel,” he says. “Sometimes on a film there might be an alternative ending, but nobody would ever release a rough draft of a chapter or of an entire novel.” And while he notes some artists still have an aversion to releasing their early sketches of songs, others have found creative ways to retain their original intent.

“Elvis Costello’s reissues, when he did them years ago, they, on purpose, put a silent gap between the original album and the bonus tracks,” says Liu, “There would be this big pause, so you could either shut it off or you knew it was letting you know that you were listening to something different.”

In many ways, these kinds of expanded releases are both a blessing and a curse. In previous decades, B-sides and alternate versions were things only heard by obsessive, diehard fans. The fact that this material is afforded the chance to be embraced by people not inclined to do the digging is a great thing. But when it comes at the expense of the initial work—the one that made you want to go hunting for every rare studio outtake in the first place—it’s easy to have that magic slip right past you.

“If I’m unfamiliar with a certain band,’ says Liu, “My first question to you is always going to be: ‘Where’s my entry point? What album should I listen to?’ You’d say the album, and I probably would go get the deluxe version, with the expectation I’m gonna like this and at some point want the bonus material. But what I usually do, is I don’t play the bonus material. I just play the original album. I’ll play the original album on repeat so I don’t get distracted by all the other stuff.”

It drives home the point that a first impression carries a lot of weight, especially in terms of music. Starting with the wrong album, or getting lost in a tangled web of extras can give a false impression of the work itself. It can turn a record you’d love into something that you don’t return to, or just plainly think sucks. That is until years later, when you realize you’ve been listening to the wrong version this whole time.