“Amateurs sit and wait for inspiration,” Stephen King once wrote. “The rest of us just get up and go to work.” In that spirit, Riot Fest proudly introduces Autodiscography, a new anthology series where we celebrate the tireless work ethic, versatility, and imagination required of our favorite prolific musicians.

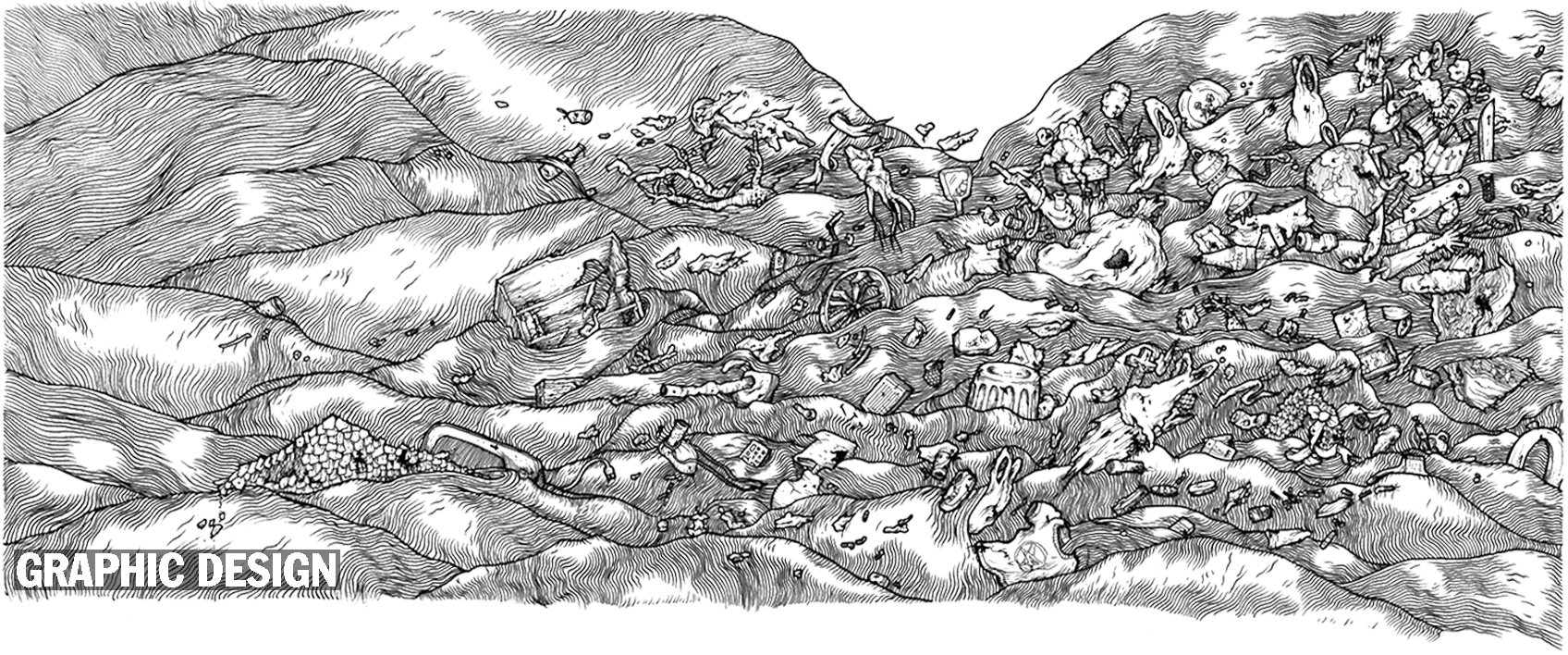

For today’s inaugural installment, we managed to corral extreme music luminary Aaron Turner during one of his increasingly rare free hours. Despite running two labels (SIGE, alongside wife and Mamiffer collaborator Faith Coloccia; and the legendary, still-active Hydra Head), co-parenting the couple’s first child, continuing to challenge himself as an in-demand graphic artist, and dividing his talents between countless active and dormant-for-now projects (Sumac, Old Man Gloom, Split Cranium, House of Low Culture, and Thalassa, just to scratch the surface), the former Isis frontman graciously opened up to Riot Fest about his lifelong creative restlessness.

RIOT FEST: Before you moved from New Mexico to Boston in the mid-90s, you played guitar in Unionsuit and Hollomen. Were those your first two bands?

AARON TURNER: Unionsuit, yes. Uh, well… [laughs] I guess it depends on how legitimate the term “band” is. The first band I was in was called the Defilers, and we did Ramones covers because our drummer was Ramones-obsessed, and I was Metallica-obsessed. We would not do any full Metallica covers; we were allowed to do one Metallica medley. There was a Defilers cassette which was released. I was not on it. They did, however, use a song that I had written, so technically I suppose that was my first sort of real band. That was in ninth grade, so that would’ve been ’90 or ’91, I think. Hollomen was like a summer project, but it was when Isis had already begun, but hadn’t really done much yet. Isis was ’97, Hollomen was the summer of ’98.

Hollomen was just a bunch of my high school buddies and me. I think we had all moved away from Santa Fe — well, maybe one or two of us had, but we all happened to be home for the summer when we were still college kids who went home to stay with mom and dad. I think we just kinda wanted to do something, and that was what ended up coming out of it.

When did you begin to develop the desire to front your own band?

Even in the early days of Isis, I didn’t want to be the singer. I was really scared to play guitar and sing at the same time. It was really difficult for me, and actually still it’s the hardest thing for me about playing music. My brain doesn’t work very well in that regard, and I’m envious of people that can do it really fluidly. When Isis started, we didn’t want to have a singer. We all just kind of felt like singers who didn’t play an instrument were lame. There’s just very few frontmen who are only frontmen that are really cool to watch and listen to. So, by default, it was just kind of me ’cause nobody else really wanted to do it. I was the only guitar player at the time, our bass player didn’t want to do it.

We definitely were not going to allow a singing drummer, because that’s also lame. Not always, but generally speaking.

I’ll let Brann Dailor know.

[laughs] Yeah. There are exceptions to these blanket statements I’m making where I’m passing judgments on a lot of other musicians. But anyway, it was just kind of me by default. We did think about at one point having Chris [Mereschuk], who was the original keyboard player in Isis, be the main vocalist, but for whatever reason we just decided that I was it, so I just did it out of necessity. I didn’t really start to like it until… maybe by the time Isis did Oceanic, I was starting to become more comfortable with singing and playing at the same time, actually enjoying it, rather than just enjoying the guitar parts where I wasn’t singing and then panicking every time I had to sing.

You founded Isis with Jeff Caxide, your roommate at the time. What do you remember about those early conversations with him about shared aesthetics?

Jeff and I ended up being roommates basically because we liked the same kind of music. When you’re young, that’s as good a reason as any to move in with someone — because you like the same bands and you like each other’s sense of humor. And I think both of us, having come from a hardcore background, gravitated towards the stuff that was more obtuse or, in some cases, even almost abstract in nature. I know we both liked things like Buzzoven, Neurosis, Today Is the Day; but also things that were a little more out there, like Earth. I know Earth 2 [Special Low Frequency Version] was a big bonding point for us. So, it was kind of this idea of taking hardcore and metal and pushing it in a more abstract direction. [We liked] all these kinds of bands that maybe had similar backgrounds in the sense that they were loosely considered metal or hardcore bands, but were pulling from a lot of different areas.

It took from 1997 to 1999 to finalize that first lineup. Why do you think it took so long?

If you look back at bands of that era, a lot of bands didn’t even last two years. So, just the nature of being young, and a lot of guys and gals in bands being transient because everything is sort of revolving around college still at that point. Nobody was ever in [one] place long enough to become stable.

I also think it was just personality conflicts, too. At that age, people are still on the cusp between being teenagers and being young adults. I know “young adult” is what people call teenagers, but I don’t think that actually applies. This is my experience anyway: You think you can play with someone because you get along the first couple times you met up, or you jammed and it’s gone well. But then you go on tour together and you’re like, [laughs] “I don’t like this person. We don’t get along. Their personal habits bug me.” That was kind of the case with Isis. Our very first tour was almost our last. We essentially broke up at the end of that tour. And then Jeff and I had a conversation afterwards, after we got home. We were like, “Look, there’s something here that we both really like. Let’s maybe try to pick up the pieces and figure out how to move on.”

I would guess the biggest non-festival audience you’ve ever played was opening for Tool. Do you miss anything about that experience? Tool fans were notorious at the time for not being kind to opening bands.

We were pretty apprehensive about that tour for that reason. The Melvins guys said that they got shit tossed at them, and the Tool guys said their fans weren’t always kind to openers. But we actually had a really good experience. We were only heckled, that we noticed, at one show on that entire tour, and it wasn’t even violent. One thing we always did to prevent ourselves from even being aware of heckling was play really loud segues between songs, so who knows? We could’ve been getting more shit than we were aware of.

We had some audiences [on other tours] where I felt there was way more animosity in our direction than what we got from the Tool audience.

We opened for Cradle of Filth, Emperor, and Usurper in Worcester, and the whole front row turned their back to us.

On the tour we did with Napalm Death and Soilent Green, there was a bunch of straight-up metal dudes that were just not into our stuff. Those experiences prior to the Tool tour kinda prepared us for getting shit here and there when we were playing to someone else’s audience.

To answer your question in terms of playing to larger audiences, I don’t miss playing to, like, Tool’s audience, for instance, because they were never our audience to begin with. It’s not like Isis was playing to 10,000 people that were all our fans, and now I’m playing to, whatever, 100 people that are fans of my new band. I do miss some of that in the sense that I liked playing clubs with good sound systems. I liked some of the amenities that came along with being in a more popular band. That said, some of my best shows, even in Isis, and even in Isis at our most popular, were to smaller audiences. And that’s not necessarily because I want to be an underdog or I like the idea of being some kind of underground stalwart. It was just, the intimacy of certain situations heightened the connection between player, music, and listener.

Four years after Isis broke up, you changed the band’s Facebook name to “Isis the Band.” Have you given any thought about what you would have done if the band were still active? [there is a terrorist organization called ISIS, and idiots have confused the two]

Yeah… and I never came up with a clear answer to that. I’m very glad that we never actually had to consider that, because it would’ve been a real problem. I’ve had two minds about it. One is that sticking to our guns would’ve been what I would have liked to have done. Simply because… I think the people we would’ve been pissing off are reactionary right-wing nut jobs, and I don’t believe that it’s good to be cowed by people with that kind of ignorant mindset. So, in that way, I would have liked to have kept the name and keep operating under that name. At the same time, because of nut jobs who are ignorant and prone to violent reactionary maneuvers, it probably would’ve concerned me in that I wouldn’t have wanted to risk getting shot somewhere, you know, because somebody thought that we were somehow supporting terrorist organizations.

Sure. Or consider a fan wearing an Isis hoodie just walking around in public today.

Yeah, people still do it.

People show up to shows for my other bands now, and they’re still wearing Isis gear, and I applaud that courage. At the same time, I wouldn’t want to do it.

Also, there’s tons of women and little girls with the name Isis, so I feel worse about that than I do about the fact that my nonexistent band now has to contend with idiots from time to time on our Facebook page.

On a lighter note, Old Man Gloom’s The Ape of God (2014) was a notorious prank in which you sent a mash-up of what turned out to be a double album to the press before release, without telling them that it wasn’t actually the album you were releasing. Taking the piss is definitely not something most people associate with you.

Part of the reason I wanna do different bands is that I don’t have to maintain a strict aesthetic within just one musical identity. I can explore different facets of my musical persona and also collective musical personas. I think that’s one of the main reasons why I’ve ended up with such a big discography. I’ve never really been the funny guy in any band that I’ve been in, but I have been in bands with a lot of funny individuals. When it comes to Old Man Gloom, I think I have some ideas that are funny, but I’m not necessarily good at telling jokes, whereas Nate [Newton, guitarist] and Santos [Montano, drummer] especially are just really funny individuals.

Old Man Gloom has just always operated under the premise of having fun.

All of us have been in — or are in — other bands that, at least as far as the public face is concerned, are very serious. So, this was an opportunity for us to not have such strict parameters that we have to operate in, in terms of presentation, in terms of songwriting, in terms of social relations and PR. You know, we can just do whatever we want to do, and I think that kind of freedom is very appealing sometimes. Especially for me during the Isis years, because Isis was such a workhorse in many ways, I needed something that felt frivolous. Music to me — I mean, if you think about the term “playing music,” for me, there has to be an element of play there. And I think that Old Man Gloom largely just focuses on that.

The thing that was funny to me about the whole Ape of God “controversy,” if you can even put it that way, was that I don’t know why anyone was pissed at Old Man Gloom. If anyone was aware of our history, it should’ve been obvious that nothing we do is serious. So, I don’t know why people took it so seriously. Then again, at the same time, I guess it was kind of a provocative move on our part, so I guess we kind of have to expect some backlash.

Music journalists tend to not have the greatest sense of humor when called on the carpet.

Boy, did we find that out. But for me, that was such a satisfying moment of kind of leveling the playing field. Because I feel like music journalists can say whatever they want in a public forum about a band’s music, and they don’t have to consider the fact that bands have spent literally months, if not years, laboring on this stuff that a journalist can dismiss in the course of a two-paragraph review. So, the fact that a lot of journalists got their feathers ruffled because we were supposedly wasting their time was definitely satisfying to me. It’s like, “I’m sorry you spent an hour writing a review about a record that is still our music, but not quite the record that you thought it was supposed to be.”

Music journalists think that they’re impervious to being beholden to anything, and finally we were able to kinda turn the tables a little bit. And a lot of people didn’t really appreciate it.

I do think that music journalism serves a point. And I’ve learned a lot about music that I’ve come to really enjoy by reading about it. At the same time, I just felt like, especially at the time when Ape of God came out, there was this serious downturn in music journalism. One, because print was already starting to die off by then, but also because there was such a glut of music and such an emphasis on creating fresh content that I felt like a lot of music journalists really weren’t paying attention to anything that they were getting. And I can’t necessarily blame them. I know editors are probably putting a lot of pressure on journalists to crank out as much as they can. At the same time, I was just like, “You know what? If people aren’t really gonna pay attention, we’re gonna see what slips through the cracks and what we can get by people.” I think there’s a lot of levels to that whole experiment that went well beyond “prank” and actually were in some ways commentary. That’s a thing I appreciate about Old Man Gloom. It is silly and it is stupid, but it has another level to it, which is maybe even philosophical in a way, and relates more to parody and social commentary than just dumb humor. We definitely walk a fine line at times, though. [laughs]

Speaking of dumb humor, you have three aliases on your Discogs page that are pretty interesting: “Fuckface Turner,” “The Turnip,” and “Ron Bradford.” Do you remember what projects those were from?

Uh, “Fuckface” I think came from Scissorfight. I don’t know. They must have credited me as that in something [they did]. I definitely never used that for myself. [laughs] “Turnip,” I’m not sure where that came from. I think Seldon Hunt or Stephen O’Malley came up with that one, so it may have been used in reference to something that they’d done. Yeah, I’ve never applied any of those monikers to myself; those have all been assigned to me by third parties.

Sumac is probably your most high-profile outfit post-Isis. It can’t be a full-time band due to [bassist] Brian Cook’s commitment to Russian Circles. How interested are you in having that type of going-concern in a touring entity once again?

I’m not. I don’t ever wanna do that again. I love playing live, but when Isis was touring four to six months out of the year, I enjoyed about one month of that. [laughs] It’s not because I wasn’t invested in the music. It was more that the rote repetition of playing the same songs over and over again made me feel like less of a musician and more of a performer.

To some extent, Sumac has been purposely structured in a different way where there’s large holes left in our songs and in the set where we can move about freely without having to adhere to existing structure. I like that, and it does help keep it fresh for me.

At the same time, even with that kind of freedom, I don’t think that I would find myself enjoying being on the road for six weeks at a time with Sumac. I just don’t want to do that. And that’s partially now because I have a child, but even before having a son, I just didn’t like being gone for those stretches of time. I like the comforts of home. I like being able to spend time with Faith, and now with Ashley, and with our animals. I like being able to listen to records and get work done. I like to do other things with my life than just sit in a van and sit in a dark club, and…

Wait around?

Yeah. Exactly.

So, it’s not just age or fatherhood or marriage; it’s growing weary of those other responsibilities, too?

Yeah. And again, this is kind of a blanket judgment on the game of rock ‘n’ roll [laughs], but I’m not a party person. I’ve always been a pretty introverted person. So, the part of the tour that means, like, hanging out with people every night and drinking or whatever every night has never been that big of a draw for me. Now, I don’t do anything in terms of getting fucked up. I stopped smoking weed quite a few years ago. I mean, I do it every now and again, but the party aspect of tour has no allure for me whatsoever.

You already collaborate with your wife (Faith Coloccia) in Mamiffer and House of Low Culture. Is it safe to say you’re settling into becoming a home recording artist?

I do like doing that. It’s also a matter of practicality. House of Low Culture, for instance, we don’t sell enough records that we can afford to record at the real studios. [laughs] Going back to Isis and how that operated, one of the things I found frustrating after a time was I didn’t have time to work on other projects, or at least not as much as I wanted to. That was something which led to me wanting to quit the band eventually — the fact that I was dedicating almost all of my music-making time to one band.

Isis dominating so much of my time was frustrating for me because it wasn’t covering all the musical ground that I wanted to cover.

So, now being at home more often means that I can have more time to explore all the musical avenues that I want to explore. I can make records more frequently. I can collaborate with other people who I’m not in bands with more frequently, and that kind of flexibility is crucial to my ongoing interest in being a music-making person.

Your list of collaborators is endless. Without asking you to name favorites, what’s a quality you look for in returning to play music with people?

As time as gone on, I’ve realized there’s lots of people who make music I like, but not all of them are people I like making music with. A lot of the people I’ve gotten to know through making music are like me, or I’m like them in that we’re introverted people. We probably were social misfits growing up, and maybe didn’t necessarily excel in other forms of communicating and socializing. So, music was almost a necessity for having friends. You had to have something to do together in order to have a reason to be together, and the creative dialogue that happened allowed for the kind of connection that maybe we weren’t able to make outside of our musical framework. I still find that to be a really interesting and actually deeply compelling reason to make music with people. Faith has also never been a super gregarious person. She’s pretty introverted, like I am. And even though we can be polite with strangers, it’s very hard for either of us to really get to know people or to be in social circumstances that are purely social.

It’s always easier for us to spend a lot of time around other people if we have some shared creative activity.

I’m also thinking of somebody like Jussi [Lehtisaho] from Circle. We collaborated with Circle, we did the Split Cranium record, we just finished a second Split Cranium record, and he’s another guy who I share some similarities with. We’re both really shy; we’re not great in group settings. Maybe even our one-on-one was verbally kind of difficult when we first met, but as soon as we decided to embark on some creative projects together, we formed a really close and sincere bond.

In Pitchfork’s (very positive) review of Split Cranium’s 2012 s/t LP, Brandon Stosuy suggests that certain scene kids might take umbrage with your stab at underground crust, the same way black metal purists might be upset with your involvement in Twilight. Have you ever encountered that type of blowback in person?

Never. All the flak I’ve ever gotten has been internet-only. I’ve never, ever once had someone come up to me at a show and give me shit about anything that I’ve done. I don’t know if you’ve heard about this or experienced this yourself, but Germans are very forthcoming with their opinions. And there have definitely been shows I’ve played in Germany where people have been very vocal about what projects of mine they like and don’t like, but it has rarely been about me as a contaminant in a particular scene they hold dear and more just about personal preference.

I did have a couple people who were upset about my involvement in Twilight because of the political implications there, but again, the only exchanges I ever had with that were via email or just stuff that I heard about circulating on the internet.

If I was sensitive to people’s opinions about what I should or shouldn’t do, I don’t think I could continue being a musician or even a record label owner.

Do you feel like fans of Isis are drawn to your drone/ambient work, from House of Low Culture to Thalassa or Lotus Eaters? How much of a crossover is there?

Not a lot. If I’m just judging by record sales alone, I’d say there’s almost none. That said, a lot of people have told me maybe they don’t like everything I’ve done, but they tell me, “I love Jodis, but I also really like what you’re doing in Sumac,” or they like Mamiffer or they like Greymachine, but they don’t like Isis.

I’d say there’s definitely people who are fans of my body of work, and then there’s a lot of people who are just fans of a band I’ve been, in and they may not even be aware that I have a career and a discography outside of that band.

Jodis seems like an outlier for you, vocally. Other than later Isis, it’s your most melodic, cleanest work. Are there any genres you feel connected to that you haven’t found a way to execute yet, say hip-hop, country, linear narrative storytelling?

Uh… I don’t know? [laughs] If you had played records that I’ve made in the last five or 10 years for my 20-year-old self, I think my mind would’ve been blown, and maybe I would’ve even been put off by some of it. There are things that I’ve done that I never anticipated doing. I never planned on doing melodic vocals, and it was something that I kind of resisted for a while… And actually have gone back to resisting. [laughs] That was always a sore point in Isis. It wasn’t that I necessarily disliked the melodic vocals I did. I just found it hard to do in a way that went beyond being an enjoyable challenge and more into something I just felt uncertain and extremely self-conscious about. And it also took it further into the realm of being “rock” music, which, at the time, and also in retrospect, is something that I was never entirely comfortable with. Jodis, on the other hand, for me, relates more to something like Codeine. It’s melodic, but it’s not “rock music.” It’s very subdued and restrained, and that is interesting to me. I don’t anticipate myself making anything as rock-oriented as the later-era Isis stuff was, but who knows?

Well, Split Cranium has elements of Motörhead…

Yeah, that’s for sure. I guess what I mean is, I have some areas that I don’t want to stray into. I think that Isis went further into a certain kind of area than I was really comfortable with. I don’t feel like going there again anytime soon. [laughs] I guess it kind of goes into the realm of “alternative metal.” As much as I don’t judge anybody for liking or being interested in a certain kind of music, that’s not where I personally wanna go. So… I don’t know.

Melody for me is a very tricky area to navigate. I’m interested in the juxtaposition of abrasive and dissonant stuff with melody and harmony, but I feel like it has to be done in a very particular way in order for me to feel sincere doing it.

I think Harvey Milk is a band that has incorporated melody into their music in a way that I find absolutely awesome and devastating.

Your Wikipedia and Metal Archives pages vary greatly on your many guest appearances. Since we can’t cover all of those, is there one in particular that stands out?

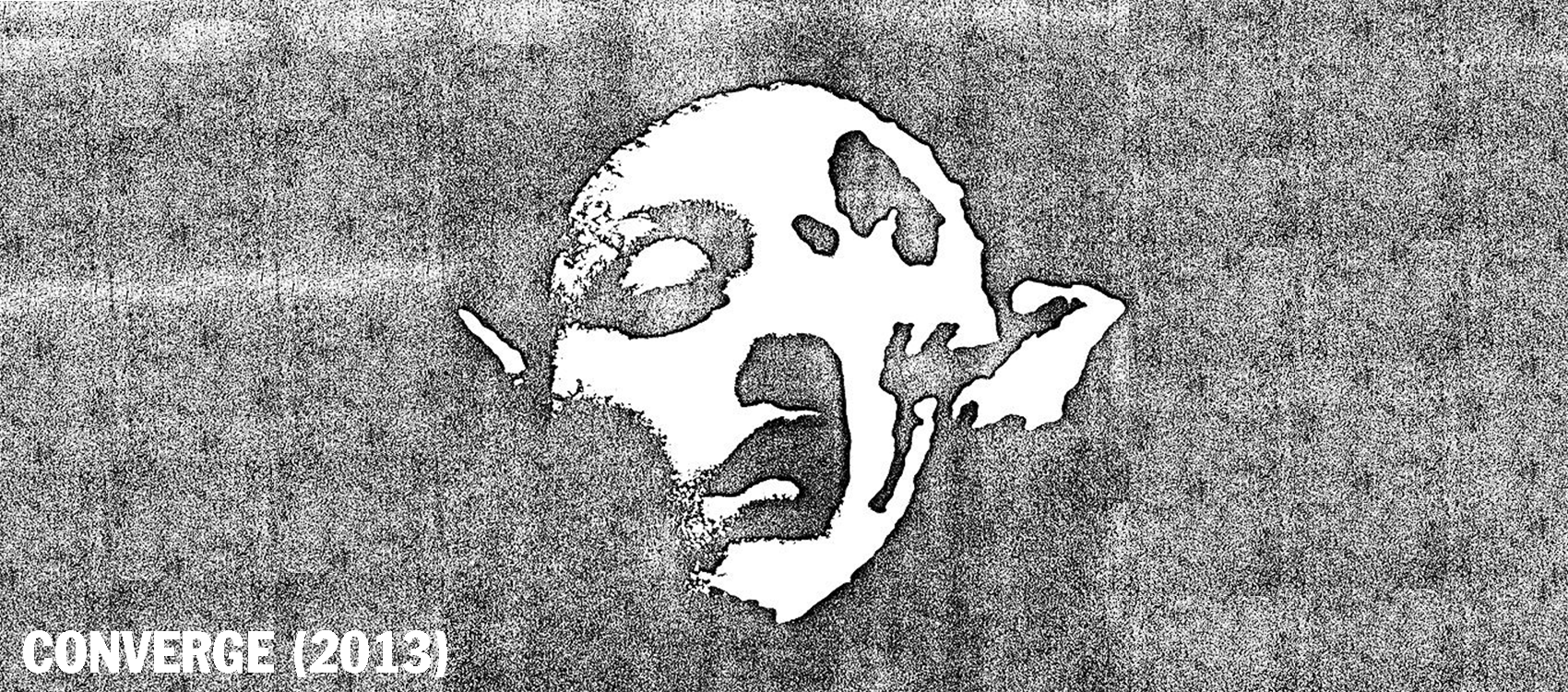

The one that was honestly the most fun for me was the Converge cover of Entombed [“Wolverine Blues”]. They did a digital EP where they had a bunch of different vocalists each singing one section of the song. Then they also released like six different versions where the vocalist did the entire song, so there is a version of that song where I sang the whole thing.

That was so much fun. I had never done a song that was that straight-ahead death-and-roll.

Also on a more personal, historical level, Converge was one of the first bands I connected with when I moved out to the East Coast, and by that I mean they’re one of the first bands that I saw live and was like, “Holy shit, this is exactly the kind of stuff that I want to be connected to.” And then I developed a personal connection to the people in the band. Jake [Bannon] and I worked on some things early on. He helped me with design stuff; he did some vocals on the first Unionsuit demo. Then I ended up recording many records with Kurt [Ballou].

To work with a band who inspired me early on when I was first becoming more deeply involved with the underground punk/metal world was an important thing for me.

Out of all the visual works of art you’ve created for your own projects, which one best captures the spirit of what the music is aiming to accomplish?

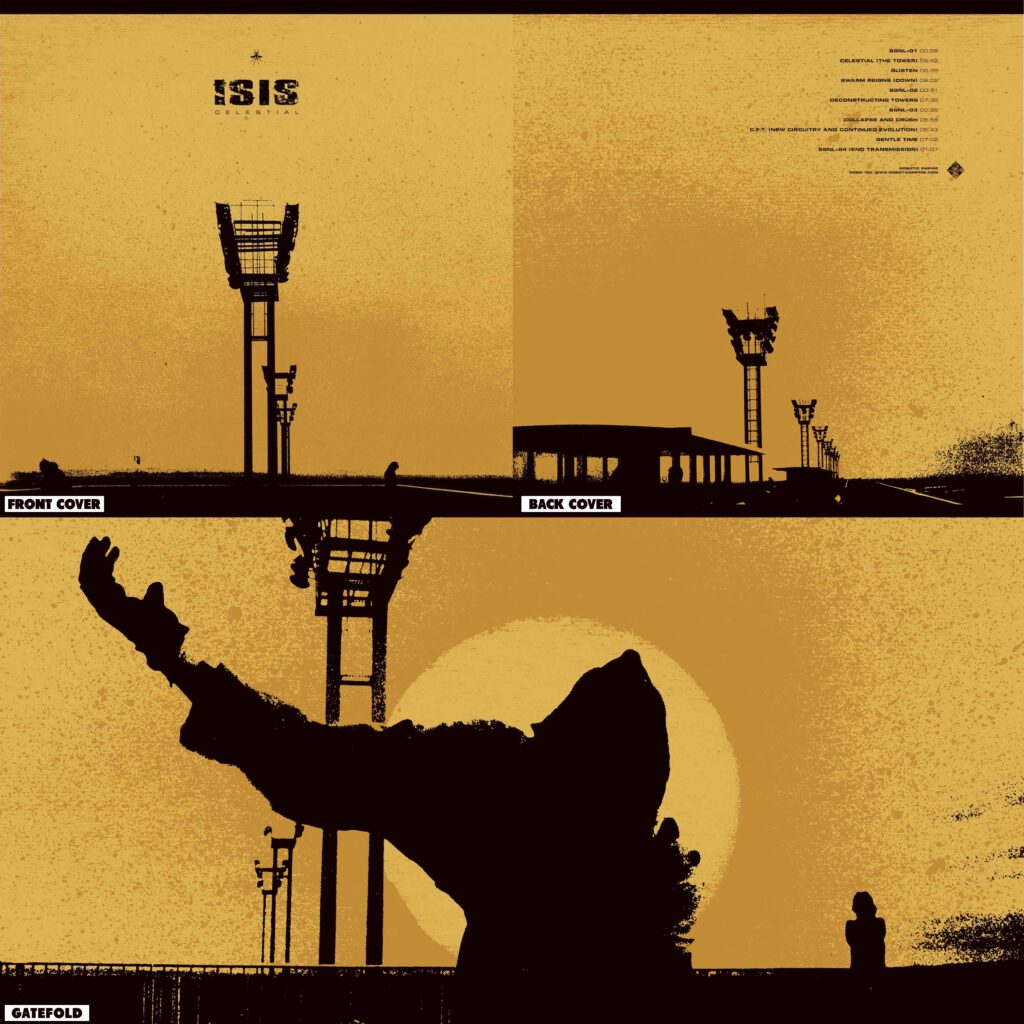

I always tend to like the things that are the most recent the best, but there actually are two that come to mind. I think the cover of the last Sumac record, What One Becomes, is a very good visual signifier for the album, and it conveys exactly what I hoped it would while also retaining enough mystery that it’s not just completely obvious. And though this is a redesign, the most recent [2013] issue of [Isis’] Celestial is really good in terms of being a representation of the album. It allowed me to take what I did with the original and kind of clean it up a bit and fit it into my current aesthetic. I feel like the cover now is almost how I wished it had looked originally. [laughs]

I always tend to like the things that are the most recent the best, but there actually are two that come to mind. I think the cover of the last Sumac record, What One Becomes, is a very good visual signifier for the album, and it conveys exactly what I hoped it would while also retaining enough mystery that it’s not just completely obvious. And though this is a redesign, the most recent [2013] issue of [Isis’] Celestial is really good in terms of being a representation of the album. It allowed me to take what I did with the original and kind of clean it up a bit and fit it into my current aesthetic. I feel like the cover now is almost how I wished it had looked originally. [laughs]

What has your experience running Hydra Head Records taught you that you’ve applied to running SIGE Records with Faith?

Some of the major lessons I learned from Hydra Head were mostly about my personal preferences. Though I’m glad Hydra Head was able to do a lot of the things we did and grow to the level we did, I also found it became extremely unwieldy in the mid-to-late period of the label where we had a lot of bands who were very active and wanted big recording budgets and wanted to make videos. And I understand that. I was in a band myself that did a lot of that kind of stuff. However, trying to support bands who need really deep resources and need a lot of attention was difficult then, and is extremely difficult for me now.

Do you and Faith have full-time staff or interns?

We have one person who helps us out. She kind of does work for both labels, and she’s only here once or twice a week.

Basically the main things I learned are: I only want to work with people I know really well and aren’t going to be shitheads; I want to work only on music that I am 100 percent devoted to — that was largely the case with Hydra Head, but there were certainly a handful of records I wish I hadn’t put out, simply because I don’t like them that much from a creative or musical standpoint. And then the other thing is just keeping it small.

I don’t want to run a big label. I’m more concerned with doing my own music and having a life outside of that than wanting to do a record label, which, especially these days, is kind of an all-consuming endeavor. If I was to run Hydra Head again as a full-time label, it would mean me stopping a lot of other things that I’m currently doing, and I don’t want to do that. I’m fully content with being selfish and working on my own records and spending time with my family.

Between the two labels and god knows how many active bands, much less graphic design work, do you ever just say “fuck it” and Netflix-and-chill?

Almost never. Faith and I tried to take our first-ever vacation this fall and ended up canceling it. So, I need to continue to strip things back further. I’ve been thinking a lot about that in the last few years. And I think it’s going to mean that the label stuff becomes more infrequent than it is currently. As much as there’s a lot of music being made that I want to get behind, I know that there are other people that will do it. So, it’s only going to be the odd record here and there with super close friends that I’m gonna get behind and put my direct energy into.

I would honestly love to have more time to sit around and read, and go for long walks in the woods.

I have changed my schedule a lot since Ashley was born. Faith and I are definitely co-parenting our child, so a large portion of my day every day is spent doing that, and happily, so I think the one area in which it becomes uneven for us is the fact that, at the moment, Faith is not touring and I’m still continuing to tour. So, that’s one area that’s still kind of tricky to navigate. But, honestly, as much as I love watching films, I’d rather give that up for the time being and spend time with Ashley, and then spend my evening after he goes to bed in the studio rather than sitting around watching a movie.

I’d rather make my own art than absorb someone else’s.

House of Low Culture’s four-way drone/noise split, “The Pervasive Mind,” which concluded Turner’s latest outrageously productive 2017, was released last December via Accident Prone.