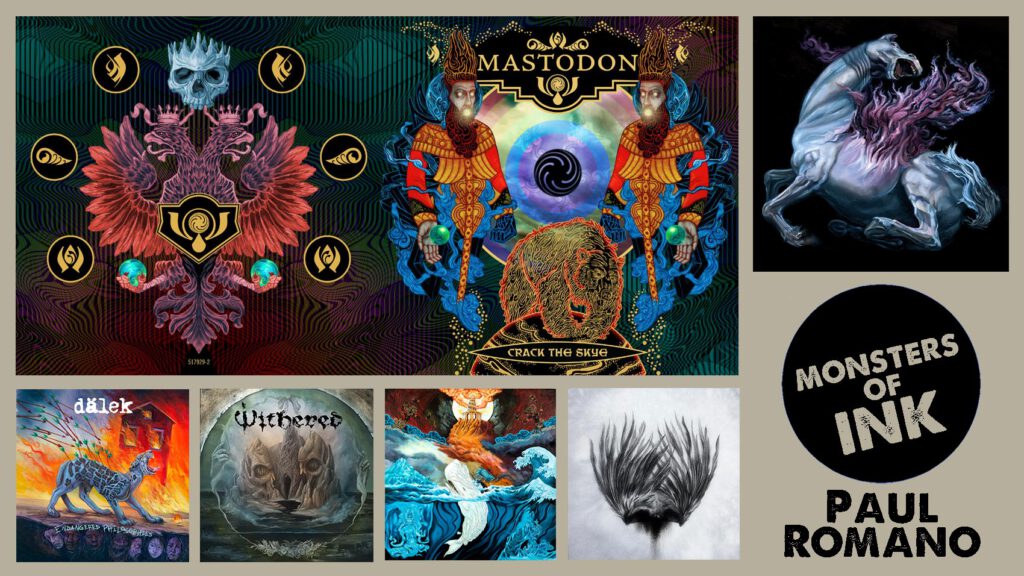

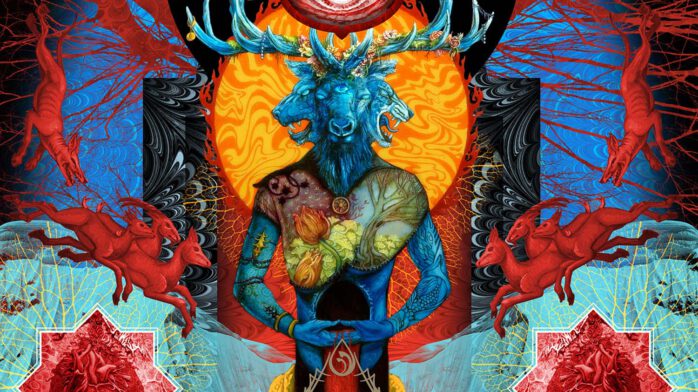

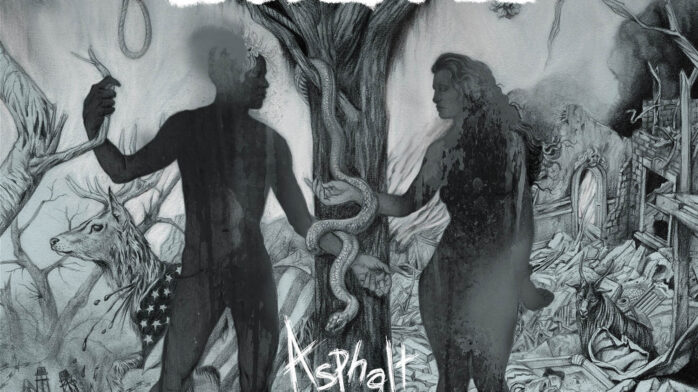

Mighty steeds bursting into flames. Sperm whales capsizing ships a fifth of their size. If you’ve followed extreme music since the turn of the century, Paul Romano’s haunting visual hellscapes have followed you right back… like it or not. The lifelong Philadelphian has lent his immense talents to local legends ranging from R.A.M.B.O. and Starkweather to A Life Once Lost and Rosetta; but our latest Monster of Ink is most notorious for having designed the immediately recognizable covers of every Mastodon record through 2011’s The Hunter.

With an intimidatingly-expansive CV that also includes Hate Eternal, Withered, Dälek, and Trivium, Romano’s art is practically synonymous with modern metal. This makes it all the more astonishing—and awesome—to learn that the likes of Rihanna are on his wish list for future collaboration. Read on to find out why, as well as how technological advances have compelled him to (hopefully temporarily) retreat from the limelight.

RIOT FEST: You’ve long been a respected, in-demand artist in the extreme music community, which must entail countless pitches from bands and labels. Have you ever flipped the script and pitched yourself to work with a particular artist?

PAUL ROMANO: I approached the first band that I felt I had to work with around 1994: the Dazzling Killmen. I was already nuts for their albums, and they’d come into the Mütter Museum, where I worked at the time. I talked with them for a bit, and we continued the conversation that evening at Khyber Pass (the venue they were playing). I was courting them hard, sending off care packages and such. It seemed like it was lining up; but, alas, they disbanded. To this day, I wish they’d put out more. I did eventually work with their drummer, Blake Fleming, on a retrospective release of his amazing angular-jazz-noise-rock project, Laddio Bolocko.

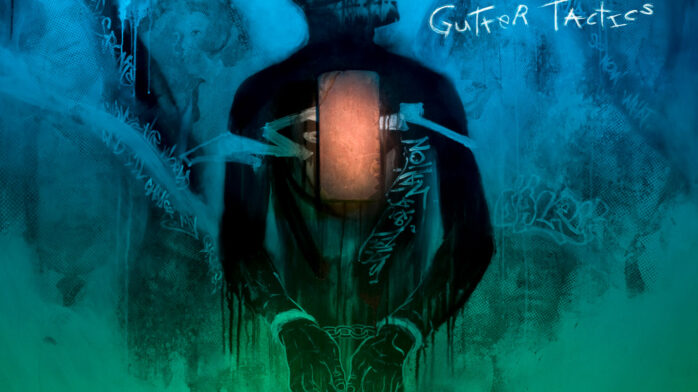

Another group I pursued that came to fruition was Dälek. I saw them open for the Dillinger Escape Plan in the late-90s and was floored. Dissonance has a nepenthe-like effect on my brain, and they’re full of that. I kept after them for a while, but they spaced every time. I finally invited myself to their hometown—around Newark, New Jersey—and locked it down for their fourth full-length, Abandoned Language. I’ve done all four of their albums since, and they still remain an all-time favorite for me.

There are plenty of bands that I’d love to work with (or have worked with minimally, but want to do more): Esben and the Witch, Efterklang, Portal, any of Justin Broadrick’s projects, [or] Swans, off the top of my head.

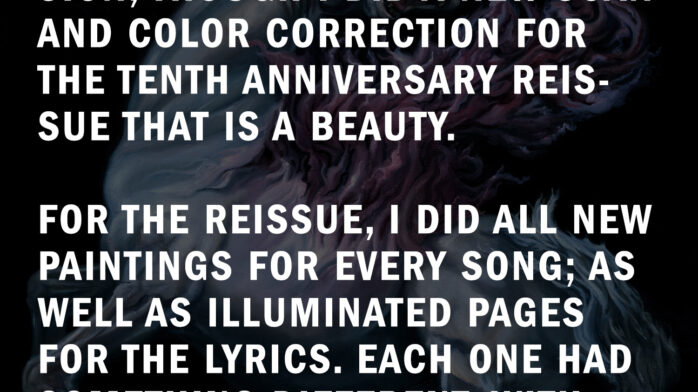

Across multiple mediums—from fine art unrelated to music to the corporate realm—you’ve achieved sustained success; but your work with Mastodon is widely considered to be iconic. During the nine years that have passed since your last collaboration with the band (2009’s Crack the Skye), have you taken any time to sit back and relish that impact, or is that sort of thing not particularly important to you?

To an extent, sure; though I might not use the word, “relish!” [laughs] I’d hoped to be creating something with longevity; something a bit timeless that had versatility. I try to do this throughout most of my work. I still see a good amount of buzz about all those early Mastodon albums and their art. Having folks still stoked on the artwork does feel pretty great. Album art was so impactful to myself, I’m happy and humbled that I got to make a contribution to its history.

To the best of my knowledge, you haven’t collaborated with musicians outside of the extreme music umbrella (obviously, it’s reductive to designate Dälek as just hip-hop). Would you consider working with a country or pop artist if they approached you? Has it already happened?

I have [worked with that caliber of artist], and absolutely would do it again; but not to the extent that I’ve done so within heavy music. I did a line of merchandise for Kesha very early on, and I’ve worked on some singer-songwriter projects.

Very recently, I worked with an artist I admire a bunch that might get a quote [on the album marketing sticker saying something] like, “Recommended for fans of Nick Cave, Chelsea Wolfe, and Neil Young.” That project is called the Dark Red Seed, and the work in those albums is my most personal work. Tosten Larson of King Dude is the genius behind this, and what he’s doing hits so many notes that resonate with my own philosophies.

Outside of that, still yes, I would love doing a project with, say, a Rhianna-type of star; but that comes from more of a standpoint of wanting to have a budget to really pull out all the stops and create an actual art object as packaging.

You’ve said you won’t work with a musician if they enter the process with a fully-formed idea. How often do musicians have difficulty articulating even the basics of what they want to accomplish? Does that make your task more difficult, or is it freeing?

If you’re approaching me, it’s to collaborate. I will listen to ideas, but I am not into a rigid vision. I don’t like being a pair of hands there to execute an idea… It’s a formula for disaster, really. I doubt I’d come close to the vision, [and I may end up having some type of] flashback to when the jocks would bully me in high school by asking me to draw their names. I like to get the broadest of strokes from the client, then dive in and create a world around that. I find nuances and references that add depth to the narrative and to the ideas within the music; [I’m a] springboard into the artist’s thoughts without being completely overt. This is very freeing.

Brann [Dailor, Mastodon drummer/vocalist] always has great narratives for their albums. He’s great with some vivid details, but keeps things very vague and open. He and I went back and forth quite a bit with ideas for Crack the Skye. I have half a flat file drawer full of ideas that didn’t make the cut.

What kinds of conversations do you have about more involved narrative works, like the Red Chord’s Clients or Crack the Skye? How comfortable do you feel revealing not only the musicians’ intent as storytellers, but your own?

Clients is an all-time favorite record that I’ve worked on, from the music to the ideas behind it. Guy [Kozowyk, vocalist] didn’t have any ideas for the visuals; but he told me about who and what he was writing about, which had me exploding with ideas. I then made a trip up [to Revere, Massachusetts] and got to meet a good amount of these people.

While I did take photos of the band and of the “clients,” I didn’t want the portraits to be representational as much as psychological. I referenced a bunch—from Victorian ideas of criminology to Frank Auerbach’s emotional/spiritual expressionist portraits. That project had quite a bit of depth for me, and I still touch on ideas that I learned there.

Having conceptualized album packaging and merchandise for over 15 years now, do you find yourself looking back and noticing a quantifiable evolution in your work? Do you ever find yourself fixated on tiny imperfections or perceived flaws that come to your attention years later?

I see imperfections as projects are leaving my hands to go to print. [laughs] Sometimes these fade away once I see it all as a physical object. Other times, yes, these imperfections are glaring. To quote the title of a favorite album of mine, “the perfect is the enemy of the good.” This is true, and remembering that is the best way to let things get out of your studio and into the world. An artist (of any kind) can spin wheels forever striving for some nonsense notion of perfection; but failing and making mistakes is part of a learning process that will only make you better.

Every once in a while, I do get to reconsider my work for an anniversary special edition. I love this, but I wouldn’t exactly categorize it as making the work better, [so much as] adding to its legacy.

Failing and making mistakes is part of a learning process that will only make you better.

You’re collaborating with far less bands these days, and have transitioned into working in tech with an AI company. What prompted that decision? Who are some of the current musicians you’re working with, and how do you manage to cherry-pick?

The decision to work with fewer bands has less to do with how the industry has changed—lower budgets, less of an effort being made for an actual object—and more to do with my own evolution. We all change and grow in our interests. My interests now concentrate more on personal works. Over the years, I’ve always taken tech jobs in short bursts, because I’m interested [or need] to pay the bills.

Currently, I’m the creative director for a company building an AI that’ll help brands deal with “big data” while being conversant with their clients. I’ve heard all the Skynet jokes. The reality is, until an electromagnetic pulse kills electricity on Earth, this is the way we’re going. Tech is now the “opiate of the masses” (bastardized Marx quote), and since we’re all adopting conveniences of technology at an alarming rate, I’d rather be on this side of the fence and understand it.

I mentioned the Dark Red Seed earlier. Other bands I’m working with in the near future are Withered, Dälek, and some others that are close to me. Mid-career with the album art, I was wearing too many hats. Now it’s more about fun… and the love of music.