“Amateurs sit and wait for inspiration,” Stephen King once wrote. “The rest of us just get up and go to work.”

In that spirit, Riot Fest’s anthology series Autodiscography celebrates the tireless work ethic, versatility, and imagination required of our favorite prolific musicians. For today’s installment, we’d like to buy an “E,” Vanna, and then solve the puzzle in the “Influential Indie Rockers” category: EMO EXEMPLAR ENIGK.

Whether he likes it or not, Seattle lifer Jeremy Enigk is a figurehead for the oft-derided genre—although he can rest easier knowing that he fronted one of its unassailable greats. Despite multiple break-ups and make-ups—the first of which resulted in bassist Nate Mendel and drummer William Goldsmith setting up shop with then-nascent Foo Fighters—Sunny Day Real Estate made an indelible imprint on emotional hardcore over the course of four albums, between 1994 and 2000. As vocalist, co-guitarist, and co-songwriter, Enigk was naturally the face of the band—a position both magnified and distorted by his unapologetic embrace of Christianity, always something of a sore spot in the secular punk rock underground.

However, that’s the underground’s problem, not ours. Enigk has always shrugged off the haters, showcasing his talents—not least of which is an inimitably vulnerable, high-pitched coo—before, after, and during Sunny Day Real Estate’s many stops and starts, be it ambitious epic-rock outfit the Fire Theft, or four disquietingly intimate solo albums. He’s about to embark on a national club tour in support of the 22nd anniversary of the most beloved platter of the latter, 1996’s Return of the Frog Queen (Sub Pop).

Want to know why he’s also been traveling the country alone to house shows, how Craig Wedren helped to shape that iconic voice, and if Sunny Day will ever enjoy a Lazarus-like resurrection? You’ll taste it in time—that is to say, mere minutes—by reading on.

POOR OLD LU (1990-1996, 2002)

REASON FOR HATE (1990-1992)

RIOT FEST: It’s a little unclear if you were ever formally a member of Poor Old Lu, or just an occasional supporting guest.

JEREMY ENIGK: No, I wasn’t a member of Poor Old Lu, but when we were just starting out as kids, I recorded a few songs with… what were we called? We had a bunch of different names. GTD was one of them, and Tears of a King was another. I’d go in and record with those guys on the weekends every once in a while. We wrote a handful of songs, but I wasn’t really an official member.

Eventually, they kicked me out—Scott [Hunter] was already the singer of the band. One day I went there and they said, “It’s not working out,” and I said, “I quit!” [laughs] We both said, “Yeah, it’s not working out.” But we were like 13 years old.

Oh my god. Okay, so, this was at an extremely early age.

Oh, I mean, it was amazing. Aaron Sprinkle was like a prodigy at that time. He was amazing back then. He could play the keys probably about as good as he can now—he was that good. At that age, he was already way ahead of everybody. And meeting him and [bassist] Nick Barber and Scott really opened up the door for me becoming a musician. Because I thought, “Oh, you can actually do this! My peers do this. This is really something that’s possible.” So, I picked up a guitar and I was on my way.

So, what was the first “real” band with you as the primary songwriter?

As a singer-songwriter, I would say—or as a singer—it would be Tears of a King. Even though I wasn’t technically… ’cause it was real music. That was probably the first introduction to being in a band. But it was a casual, every-once-in-a-while thing—a recording project. Since we were so young, we didn’t really have a lot of opportunities to play and stuff.

But the first band that I was in after that was a band called Reason for Hate, which was a punk rock band, and this was years later. I got into the punk rock movement in the 90s, the underground scene; the whole grunge thing was bubbling up. I was just a guitar player/songwriter for that band. That included William Goldsmith, Mark Swanson, and some other friends. That was just a punk rock thing.

SUNNY DAY REAL ESTATE

(1992-1995, 1997-2001, 2009-2013)

From what I understand of Empty Set, it seems like it’d be a pretty big transition from their more hardcore stylings to what eventually became the Sunny Day Real Estate that we know via Diary. What are your recollections of that evolution? I know William introduced you to Dan [Hoerner, guitarist] and Nate, right?

Yeah. We all were going to these punk rock shows in Seattle. The punk rock scene and hardcore scene in Seattle at the time was vibrant and amazing. All the bands would sort of switch off on weekends.There’d always be some sort of big punk rock band coming from out of town, but we all went to the same shows. William playing in Reason for Hate introduced him to a whole other crowd of musicians, and Dan and Nate as well. I think they were called Empty Set at the time—it was essentially Sunny Day Real Estate.

Eventually, William was like, “Hey, there’s this singer, he’s a friend of mine. We really should try him out.” Nate went on tour with Christ on a Crutch to Europe for like two months. It was a really long time. Dan and Will were kind of bored—and we got together and started jamming just for fun. We wrote essentially the majority of Diary, which we called Thief, Steal Me a Peach. And it was just a side project.

We played a couple shows as a three-piece; Dan was on bass. I remember Nate saying that Dan was his favorite bass player ever back then, because he played it like a guitar [laughs]. He played chords on it. Like, he hit the strings really, really hard. Then we had this big stressful moment where it was like, “Nate’s coming back home from tour,” and Dan and Will just decided that they really wanted me to join the band. But they needed to convince Nate, and they thought it would be this big thing that he’d say no, and Dan had this elaborate plan to make it work. And Dan brought him up to his room and laid it out, and Nate was just like [casual], “Yeah.” [laughs]

That seems like the least tumultuous thing that ever happened over the course of Sunny Day’s career.

Right. Yeah, thank you. Nate has always been the least tumultuous [band member].

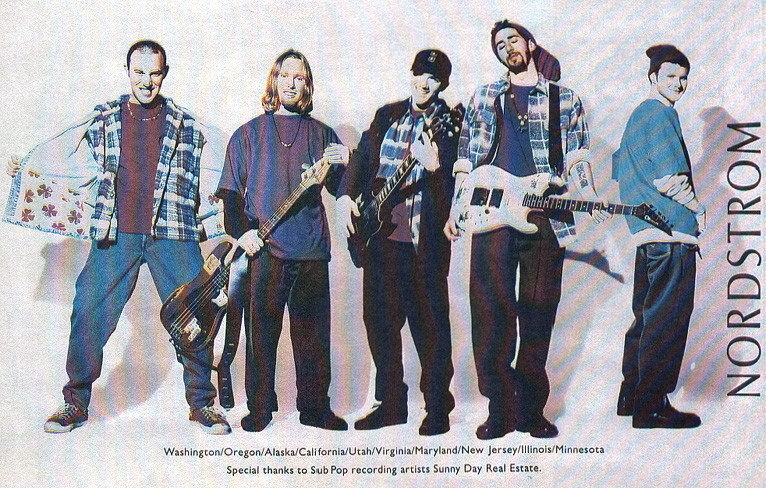

Sense of humor isn’t exactly the first attribute that one would apply to this band, but the infamous Nordstrom ad happened before anyone even knew about Diary, right?

Yeah.

Eventually the band did a total 180 on its policy about limiting interviews and press photos. Does any part of you regret not showcasing that lighter side of the band more often?

Not really, because it worked for us at the time, you know? It just worked in our favor. It was a different time, when there wasn’t really internet. Everything was word of mouth. The mystery sort of made it work. Everybody went to live shows and experienced these things, and that was the energy of what it was really all about, at least in my opinion.

Had people known the kind of brilliant comedian that William is, it would’ve been pretty amazing. All of us had a pretty good sense of humor and had a lot of fun. I think part of the seriousness for me, is that I was really nervous in any kind of limelight. When things would get, you know, intense, or we’d play a show or whatever, the way that I’d cope would be to become solemn and serious. But then I’d go back home with the guys, and we’d be playing around and goofing off.

Is that still the case?

No, no. I’m definitely more loose on stage. I don’t get nervous or any of that kind of stuff—and I might say a little bit too much on stage now. I kind of ham it up a little bit, but I think that happens when you get older.

Did you ever run into legal barriers appropriating Fisher-Price figurines, either for the cover to Diary or the “Seven” video?

Nope. And I don’t really remember why, but I do remember vaguely just someone saying, “Yeah, it’s not an issue. There’s no legal recoil from this.” I don’t know why? Maybe we shouldn’t be talking about this. [Laughs] It was a fairly known record and that Chris Thompson artwork is pretty iconic.

As bad as the circumstances were surrounding your first break-up, I found it kind of funny that you invented lyrics for some songs on the “pink” album [1995’s Sunny Day Real Estate] just to finish it off. Did you ever revise and add real lyrics?

Yeah. They’ve been completely turned into real lyrics. There was always imagery of real words in there—in a song like “Iscarabaid,” and primarily “Grendel,” too (although that’s on Diary)—when I was trying to speak Greek. [laughs] I had this Greek translation book, and I would just put little sentences together from Greek without using real grammar.

Anyway, the lyrics evolved. That’s how Sunny Day worked, too. I’d sing with syllabic rhythm and melody, and then we’d sit down and put words in places—words that sounded like what I was saying. And it’d create some very haunting poetry and profound statements at times. The song [would] create itself a lot that way, unexpectedly.

So, yeah, “Iscarabaid” is one that has real lyrics and there were real words. It was just stream of consciousness type stuff; live takes, and picking the best takes from the emotional content.

Did the appearance of “8” on 1995’s Batman Forever soundtrack—now regarded as one of the best of the 90s—have any effect on increasing your fan base during the breakup?

I’m sure every little bit [resulted in] increases. I wouldn’t be the one to say how much or any of that… but during that time, wasn’t U2 on that as well?

Yeah. And Seal.

I should actually know that, because it’s the only record that we ever got a platinum [RIAA designation]. And it was only record I ever will share with U2, which is pretty huge.

At that time, I went to Dublin—and this was kind of telling for me—I just went on a vacation to Dublin, and I walked into a clothing store, and “8” was playing. And that was crazy to me. Because I’d never experienced anything like that. I’d never been overseas. And I went up to the woman working there, and I was like, “Hey, this is my band!” And she was like, “Okay… can I help you?” [laughs] I’m like, “Like me! Like me!”

After having such a notorious (initial) final show at the Black Cat in D.C., what was it like playing your first show back off of How It Feels to Be Something On?

Oh man, I don’t even remember. I think that might have been… where was that? The Moore Theatre in Seattle? We played with Jeff Palmer, the bass player of that record. If anything, I was probably extremely nervous. Like, I can’t even see anything, really. I have very few memories of that.

Other than that, we came out and were a little nervous that we’d be playing How It Feels in its entirety, while be scrapping the majority of Diary and the pink record until the encore. Which was something that we decided to do, because we felt, in some way, almost like a new band. We wanted to be acknowledged as something new. We wanted to leave that past, and we wanted to start fresh. How It Feels was an amazing representation for us for that. So, it was almost for ourselves more than for the fans, I think.

Sonically, too, it’s very unlike its predecessors. You and Dan wrote it face-to-face on acoustics. There’s a lack of any distortion whatsoever on the whole album.

Yeah, and it was also recorded by Greg Williamson, who always has had a punk rock, lo-fi quality about his style of recording. That added a grittiness to [the record]. It didn’t have that pop sensibility; it wasn’t pushed at all in that direction.

THE FIRE THEFT (2001-2004)

Sunny Day’s The Rising Tide was your first larger than life, grandiose type of record. I feel like that’s a quality that continued on the Fire Theft’s lone s/t LP; and to a lesser degree, your first solo album, Return of the Frog Queen. What inspired that?

Well, I will say that on The Rising Tide, I was really adamant about creating something. I was really into U2’s The Unforgettable Fire. I wanted that type of production. And even though it’s not really there, it’s something that I kept on mentioning—that I wanted this level of exploration and lushness, and I wanted that sheen over it that made it a very produced record. And that’s what Lou [Giordano, producer] delivered. It’s heavily produced and full, where most of our earlier records had space and emptiness. The band just kind of did the job, not the production.

To me, I can see how The Fire Theft would be an extension of The Rising Tide, but I don’t connect it production-wise. Because a lot of that was Brad [Wood, producer/engineer/mixer]. And the majority of it was myself just in the basement of a house that William and I lived in for a very long time, just recording and trying things out. I’m not a producer or a great engineer getting good sounds, so I think there’s some of that lo-fi in there because of that. If you hear any of the quality and high-level production, that’s Brad Wood, because he’s an experienced and amazing producer.

A lot of fans do characterize The Fire Theft as Sunny Day’s fifth and as-of-now final album because it had all the original members except for Dan. Why didn’t participate? Was he asked to?

No, I think with the [record label at the time] Time Bomb thing falling apart on us, William and I decided, “Let’s just start a new thing and move into a different direction.” We then asked Nate to be part of it a little bit later.

JEREMY ENIGK

bat

It’s interesting to me that your most recent solo tour comprised of house shows, and now you’re doing a club tour for [1996 solo debut] Return of the Frog Queen’s 22-year anniversary, which is a weird number.

Yeah, we sort of missed the 20 [year] mark.

What advantages are there to performing on stages of that size?

What makes Frog Queen charming for me is the fact that there’s this chamber orchestra on it. And it was absolutely essential if I was gonna do a reunion tour of this that I had some element of that to bring with me, since I’d been playing acoustic for so long. I just cannot perform this record without the bigger ensemble, so it’s going to be a four-piece band with cello, violin, and a keyboard. It’s as stripped-down as I can afford, and as the tour’s gonna allow. Otherwise, man, I would have cello, probably two violas, two violins, flute, clarinet, French horn, and maybe even a timpani player.

You can’t do something like that for the last show in Seattle, just with locals?

Andrew Joslyn is the guy who’s arranging all this stuff, arranging the strings and everything. It’s something that we’re trying to figure out if we can pull off. Number one is finding the musicians, which shouldn’t be a problem in Seattle. But we’ll be playing at Chop Suey, which has kind of a small stage. But it isn’t in the budget [for a tour]. It’s an expensive tour, that’s just the reality—it needs to be paid for. There are a lot of people to pay. It’s a long tour—hotels, you know, everything. We’ll see… W e’re still trying to arrange for something bigger.

It’s cool that you preceded this with house shows, but it seems criminal that you’re self-booking and doing PledgeMusic campaigns for new albums. Is there really no label interest that would suit you?

To probably my detriment, I’m not somebody who has ever been interested in selling myself. I’ve always just been interested in the musical aspect. And it is to my detriment, because I have to hustle without a label. But music to me is a meditation. If something is happening in my life, it’s an opportunity for me to sit and reflect and allow that music to speak for my emotion, and get my emotion out in some structural way.

So, yeah. It is what it is, but I’ll tell you: I absolutely love these house shows. It’s a change in pace, but it’s humbling, I get to meet people. This last one I did was so amazing. I went by myself, and I had these long drives, and it was the most healing and meditative thing for me. I’d turn off the music, turn off the podcast, and just drive for six hours. [I’d] talk to myself [and] think about things that I needed to work out. It’s the road to peace, which is what I long for. I want peace, man. And being on the road is the greatest thing.

In the late 90s, your intended follow-up to Frog Queen ended up turning into a substantial portion of How It Feels. It took another 10 years for you to release World Waits. How do you think World Waits compares to what you originally envisioned as your second solo album?

Well, I don’t want to disappoint any of my fans, because World Waits is a lot of people’s favorite record of mine, which is surprising. To me, it didn’t really stand up to what I wanted it to be. And primarily it’s because of the production. I was also experimenting with this phase that I wanted to be this singer-songwriter. At the time, I was really into John Lennon—I’ve always been into John Lennon’s music, but I was like, “I think that’s a direction I sort of want to go.” It was when home studios really started to get on the rise. Everybody could record a professional-sounding record in their bedroom at an affordable rate. And that’s much more what we were doing. And it changes the dynamic, because it became much more of a recording project—which was what I wanted.

I think one thing I’ve learned from that is to write the songs and play them a bunch before you go into the studio. This is essential. Then you record it, because then you have time to really develop and explore all the avenues that the song is. The less you do, the better it’s going to sound. My trick back then was just pile on more stuff. [laughs] If it doesn’t sound good, turn up the reverb and pile on more stuff!

And, please, no offense to anybody that might love that record—it’s just my personal opinion. But I’d like to revisit it, and actually remix it in a way… because I love the songs. I want to dial back some of that production. Basically, I want to pull a George Lucas on one of my records. [laughs]

Your lone film score credit is for contributing music for the 2003 indie The United States of Leland. Have you not been asked to do that type of thing again? Do you have any aspirations to do more?

No, I haven’t been asked again. That [project was due to a] very passionate director, Matt Hoge, who’d not accept anybody but me. That was his vision. He pushed me and pushed me and pushed me, and he just would not accept “No.” Finally, he flew out and showed me the original movie—before the music, of course—and I was like, “Wow, man, this guy’s really passionate, and it’s a good movie, so yes, I’ll do it.”

I was in the middle of recording The Fire Theft, and I couldn’t walk away from that project. But William was absolutely supportive of it and said to go for it. I spent the next three months pumping that out as fast as I could.

I don’t want to get into the “what does it all mean/godfather of emo” stuff, but who is a band or artist that has named you as an influence that you really enjoy?

Man, that’s a hard question, because I really don’t know. Especially in the emo scene. I haven’t heard a lot of quote-unquote emo music, people that would call themselves emo. I’d have to think about that.

Maybe someone that you’ve collaborated with? You did a song with mewithoutYou.

Yeah, yeah. That was a nice experience, but I didn’t really work with them. Brad sent me some of their material and asked me to do it, and I sang on it, and they loved it, and then we met. [laughs]

But as far as touring… actually, I have one. One of my favorite tours—and I’m not gonna assume that they were huge fans, but I should—was Shudder to Think with Sunny Day Real Estate. I was a huge Shudder to Think fan, and Craig Wedren, the singer, had this high, really beautiful and melodic voice, and it encouraged me to let that out. I was in the punk rock thing—I wanted to be cool, I wanted to be tough, I didn’t really want to go there, but Craig was like, “No, you can be beautiful and punk at the same time.” So, that was an amazing experience.

Another [memorable] tour we did was with Soul Coughing, which was one of the coolest [co-bills] as well. We were so dynamically different, but for some reason, the synergy between the two bands worked so well. Not only musically, but as people—we got along. It’s really hard to find pairings in shows that have something special about them. And that was one of those magical things—you could enjoy both bands. I think I opened for them with Return of the Frog Queen as well, which was another dynamically cool set.

It’s been four years since Sunny Day’s Record Store Day split with Circa Survive, and radio silence since. Will this world ever hear a fifth Sunny Day album?

Oh man. I don’t know. I mean, nothing’s being planned right now, at the moment, but… you never know.

Was there an aborted fifth album?

I’m not going there. I don’t wanna reflect on that. But yeah… you never know. [pause] I will tell you that I miss it.