There was a moment five or six years ago when it felt like everyone I knew who read zines was reading Chicago writer Jonas Cannon’s Cheer the Eff Up series. Structured as a long letter to his then-unborn son, the plain-covered zines seemed to hold surprising, quiet little secrets about the world that I hadn’t seen on the page before.

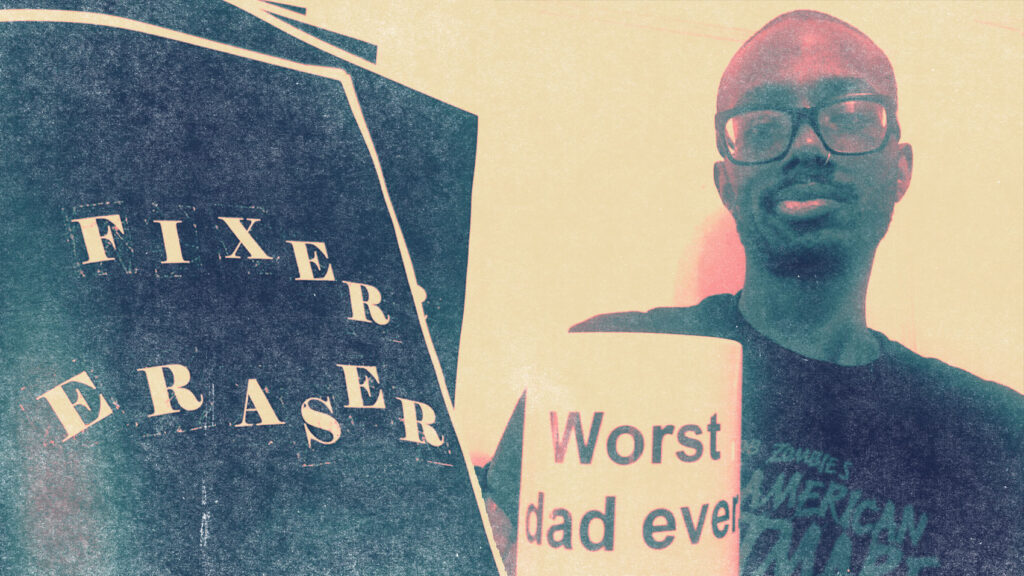

Around this time, Sweet Candy Press released his short story collection The Greatest Most Traveling Circus; in the years since, he’s edited a half-dozen compilation zines on mental health, body image, and parenting, all while struggling with recurring health issues that have required several surgeries and long hospital stays. I talked to Cannon on the phone one night last month after he put his kids to bed to discuss his latest zine series, Fixer Eraser.

RIOT FEST: I’ve been so impressed over the years with your output. You live such a seemingly busy and stressful life, but you continue being so prolific. Tell me a little about this where this creative drive you seem to have comes from.

JONAS CANNON: Well, the health issues I had—which flared up around 2013 and got really bad around 2015—it kind of just drained and sucked out all of the creative energy that I had. Especially after the big surgery I had in 2015, I just stopped writing completely. Stopped writing, stopped reading, everything just kind of shut down. And I just went into this recovery mode that lasted probably about two years. I tried to stay creative by editing zines and laying them out, doing little collaborations, but I wasn’t writing myself—really at all.

Then 2018 hit, and it just came back. I had promised myself I would go back to writing again and things just fell into place. It’s not like I forced myself, the ideas just kind of came back. It felt like the floodgates opened up, and I just rode the wave. Like, this year I’ve already done two zines and I’m quickly working on a third.

I really love what you’ve been doing with the Fixer Eraser series—in large part because I don’t know how to categorize it.

You and me both. [Laughs]

In the series, it feels intentionally unclear what’s fiction and nonfiction—they’re prose pieces, but they sound and feel different than the sort of prose you find in most literary journals. Do you have a specific concept or idea behind it?

Well, a lot of the more conversational pieces I have in Fixer Eraser are based on actual conversations I’ve had. One problem I have is I really hate transcribing. So I have these conversations and I won’t record them or write them down after. Then when I go to write them later, I pretty much write everything I remember from the conversation and the rest just goes to creative license. But the essence of it is exactly as the conversation went; I don’t change anything about that.

Some of the other pieces teeter the line between fiction and nonfiction. For instance, there’s one called “Speed Friending,” which takes the idea of speed dating—which is no longer a thing, really—and imagines it applied to making close friends. In it, the narrator—who’s basically me—goes into his most personal, intimate details, and when I started it I was like, “Am I going to embellish this? Is this going to be part fiction?” And then I just said no; the whole point of this is to share as much as possible and see what intimacy means when you share every personal detail.

As soon as I realized that, I just decided to spill out every personal thing about myself. It’s all right there. Anyone reading it, it’s just there; I have nothing left to tell you. But if you meet me in person, what does intimacy mean now that you know all of this? I think that’s what I’ve loved about perzines [personal zines] all along.

This series is fairly different than any of your other zines; what kind of reception has you received from readers?

Actually very positive. With Cheer the Eff Up I was, beyond everything else, really focused on directing it toward my child. It was a long letter to my son, for when he came of age. No matter how many people read it, or how many people didn’t read it, that was always my main intention. Moving away from that, I felt I could explore a more creative style instead of a very direct address. There was just more room for more varieties of tone and voice.

When I read your work, I always feel like there’s something you’re pointing to—like something you want your reader to know or remember about life on Earth. Is there any truth in that?

One thing that shows up in almost every issue of Fixer Eraser is dealing with feelings of detachment. Not necessarily getting away from the feeling or making it go away, but connecting with someone else who also has that feeling of detachment.

And while there’s not anything I want someone to learn, per se, with every piece I’m looking for someone to read it and say, “I needed to read this; I needed to know that someone else feels this way.” And I suppose that’s probably something that most people who write perzines feel or want. But I always say that, when I write a zine—whether it’s on the more fictional side, or a more obvious perzine—the best-case scenario in mind isn’t someone saying “I really enjoyed that,” it’s someone saying “I’m really glad I’m not the only one who has these thoughts.”