The camera shakes, the pictures blurs, the lighting leaves a lot to be desired, and the stage is nondescript in the manner of suburban VFW halls. Four-fifths of My Chemical Romance avert their anxious eyes away from the crowd. Only frontman Gerard Way makes himself available to their locked gaze. He’s in an ill fitting suit, dripping in fake blood, screaming straight from the gut: “Just! Because! My! Hand’s! Around! Your! Throat!” The microphone is in his mouth; it might as well have traveled down his throat and struck his heart. His hands are folded behind his back, and he’s bobbing his neck back and forth, up and down, both mimicking awkward fellatio and performing some perverted contortion, a traveling freak show.

The clip, captured in their 2006 documentary Life on the Murder Scene, is likely shot at one of My Chemical Romance’s earliest shows in 2002 or 2003. Even then, something peculiar was happening: one of the biggest rock bands of the millennium was performing like they already knew what was to come.

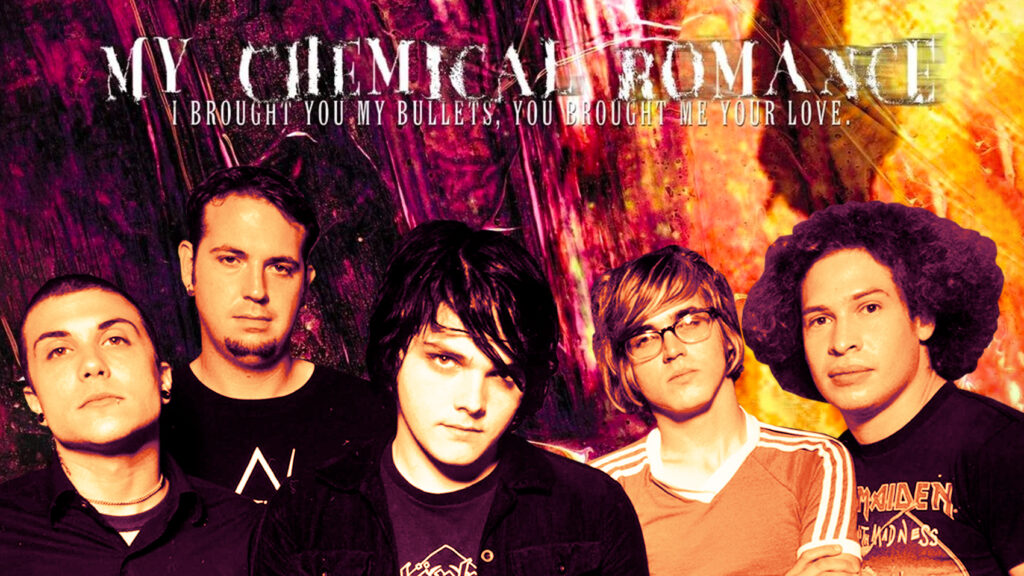

Before the bulletproof vests, the black military uniforms, and the critical reevaluation of what is maybe the most influential rock ‘n’ roll band since Nirvana, My Chemical Romance were horror nerds from New Jersey. They were a group of high school outcasts like any other, fortified by an undeniable ability to articulate the histrionics of adolescence, the torture of mental difference, the terror of being shoved into a locker too many times into song. And it started 20 years ago, when they recorded their first full-length LP, I Brought You My Bullets, You Brought Me Your Love at Nada Recording Studio in New Windsor, New York in May 2002 over two weeks. It’s all they could afford. And it paid off.

My Chemical Romance was born out of 9/11. After watching the Twin Towers fall, frontman Gerard Way abandoned a nascent career as a cartoonist and illustrator for places like Cartoon Network to write vaudevillian gothics on guitar: emo and Misfits-informed horror-punk, filtered through his ever-present love of Britpop and glam. The band formed quickly: metallic virtuoso Ray Toro on lead guitar, hardcore spazz Frank Iero on rhythm, bookish Mikey Way on bass, rounded out by local drummer Matt Pelissier. Bullets has its own folklore: Mikey Way, then a 21-year-old intern at Eyeball Records, cornered Thursday’s Geoff Rickly at a house party and told him that his new band, titled My Chemical Romance, had a song, “Vampires Will Never Hurt You,” that he would love. He convinced his brother Gerard to play it then and there—begrudgingly—in an attempt to convince Rickly to produce his nascent band. (Thursday had just released their fan favorite LP, Full Collapse, becoming New Jersey scene celebrities in the process.) It didn’t do much to sway Rickly, except, of course, a few days later Mikey tossed the Thursday frontman a CD demo of the track—a vampire noir with a 187 BPM tempo, the first time Gerard had ever heard his voice recorded—and it was clear: something special was happening. Rickly produced the album, his first time behind the board, and the magic was captured.

“Teenagers will always feel like dying. On I Brought You My Bullets, You Brought Me Your Love, My Chemical Romance found a way to tell them to keep on living.”

I Brought You My Bullets is pained, raw, raucous. During the recording, Gerard had some dental procedure, a sore jaw, and after Eyeball Records co-founded Alex Saavedra clocked him in the mouth, it was physical agony that allowed him to deliver an in studio-performance that mirrored the intensity of his o-stage power. (It didn’t hurt that he could actually sing, unlike his many tone-deaf screamo contemporaries.) MCR didn’t sound anything like the third wave emo in the scene at the time, like Brand New and Taking Back Sunday, or the downer pop-punk of Jimmy Eat World and Saves the Day—it was all of that, filtered through Manchurian riffs, theatrical percussion (hell, the thing kicks off with a haunted take on “Romance Anónimo,” a guitar instrumental dating back to 19th century parlor music), embellished with the tongue-in-cheek darkness of Way’s comic book ideologies. Demons became catalysts for real life problems like antidepressants and alcohol abuse (“Honey This Mirror Isn’t Big Enough for the Two Of Us”), PTSD, and suicidal ideation (“Headfirst for Halos,” where Way sings, “And as the fragments of my skull begin to fall / Fall on your tongue like pixie dust / Just think happy thoughts!”).

The entire album is hyperbole—earnest with some bite, but no irony—a request to the listener to find some metaphorical solace within its riff. On the surface, a lyrical line like the one in “Halos” is ripe for an AOL instant messenger away message. In practice, it allowed outsiders experiencing MCR permission to exorcize the high drama of their mundane lives, to feel included in their narrative storytelling. Teenagers will always feel like dying. On I Brought You My Bullets, You Brought Me Your Love, My Chemical Romance found a way to tell them to keep on living.

And they did it with style. “Skylines and Turnstiles” devastates with the specificity of a country dirge; “Demolition Lovers” is a conceptual narrative of two lovers, lost in the Twin Towers rubble—in many ways, it is a concept album about 9/11, chock full of so much larger-than-life aspiration, it’s easy to forget it was record by a couple of geeks in the suburbs like any other. “Cubicles” is a dystopian workplace romance, where the doomed lovers internalize the depressive mundanity and purposelessness of their laborious setting. At every corner, there’s a new sonic structure, a new harrowing topic to slide tackle, capture, and tyrannize into something resembling desire.

Objectively, I Brought You My Bullets is MCR’s most challenging record to listen to—it comes from the punk basement world, and it doesn’t shy away from that—but the energy inherent in its math-y riffs and ascendent bridges is not just the result of the chafed conditions of its recording. It’s a sense of ambition and cinema: emo in its emotionality as opposed to any dependency on palm-muted power chords. The record is anguished, hook-heavy, and haphazard-sounding 20 years later if only because we know what the band would become.

“My Chemical Romance, even at its earliest stage, were an act with a specific message: pain, trauma, loss, whatever—it can be transformed into art, positivity, and hope, without placing it in a neat package.”

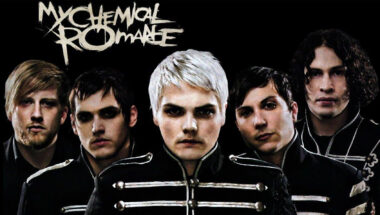

Unlike the bravado of other New Jersey/Long Island emo bands, MCR, even at that stage, embraced a sort of femininity and performative gender fluidity (credit due to their first manager, Sarah “Ultragrrrl” Lewitinn, and their androngynous English idols) with theatricality; seedlings of the Queen-shaped tree that would grow on the band’s most commercially successful album, 2006’s The Black Parade. When MCR released I Brought You My Bullets, it was clear they were on the cusp of greatness—they were the odd men out in a sea of Warped Tour-wannabes, most of which were obsessively writing songs about murdering the woman behind their unrequited crush.

MCR instead built a world of optimism without veering away from the pain. They embraced it and created beauty. Consider that ideology the spiritual precursor to their 2004 platinum-selling single, “I’m Not Okay,” and the radical destigmatization of depression at a time when our pop stars did not talk about mental illness. My Chemical Romance, even at its earliest stage, were an act with a specific message: pain, trauma, loss, whatever—it can be transformed into art, positivity, and hope, without placing it in a neat package.

In alternative music history, counterculture moments are born out of urban environments—students and kids on the dole, all motivated by art making and sociopolitical ambition, take to the city streets to make some undeniable theme, a moment, a movement. Third wave emo and pop-punk were suburban movements: middle-class angst, uncool by traditional metrics of cool, and deeply imaginative. That’s the thing about the suburbs: when there is no bohemian utopia to escape into, and the only accessible reprieve is the notion that you may one day leave your godforsaken town, forcing artists to live in their heads. They create their own worlds. My Chemical Romance became characters on Bullets, and in every record afterward, because they had to. And, as history has proven, a lot of other people needed them to, as well.