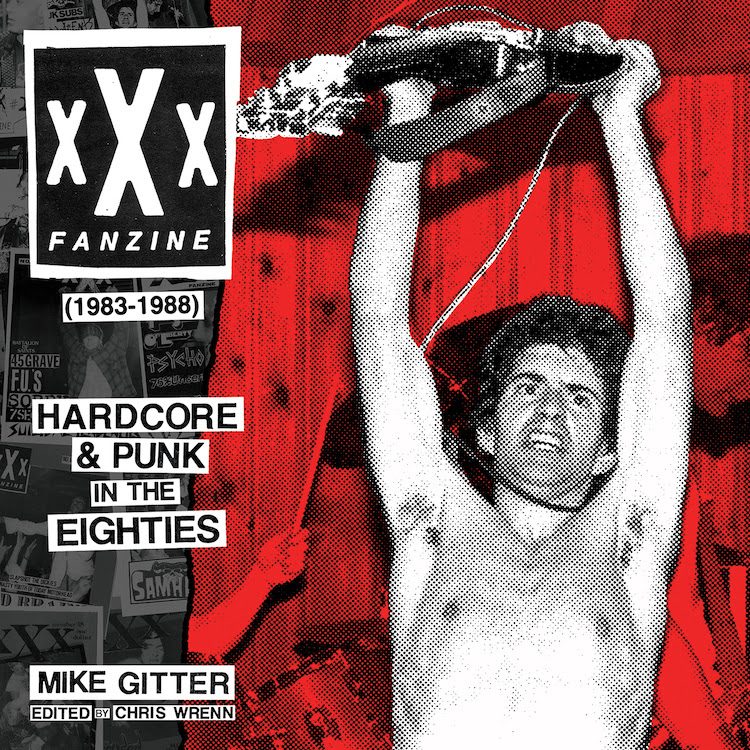

As founder, writer, and editor of xXx fanzine, Mike Gitter was down in the sweaty trenches during the politically charged Reagan age, documenting Boston’s hardcore punk scene at the height of its power. A typical issue of xXx, published from 1983 to 1988, included interviews from punk giants like Cro-Mags, Husker Du, Circle Jerks, Dead Kennedys, Minor Threat and The Adolescents.

Several years ago, Gitter–with the help of Bridge Nine owner Chris Wrenn and Al Quint, editor of Suburban Voice zine–returned to his 20-issue baby and its 500-page goldmine of artist interviews, photos, concert fliers and reviews, and distilled it into a potent concentration of the best moments in Boston punk rock in the 1980s. The book, xXx Fanzine (1983-1988) Hardcore & Punk in the Eighties is out today Orders come with a 19-song download compilation of punk covers by bands like Strife, Fuck You Pay Me and Voivod.

Riot Fest spoke with Gitter at length about covering the Boston hardcore scene, his favorite moments of covering it, and why you can never go back. (Al Quint also provided clarification for names and places.)

Riot Fest: What were some challenges to putting the book together?

Mike Gitter: I wouldn’t call it so much a challenge as I would call it an aspect of making a voice heard, which is probably one of the greatest things about hardcore punk. Part of the entire DIY movement is we all have that outlet. We all have that ability to self actualize and make our voices heard above the din.

RF: How did the book end up at Bridge Nine?

MG: I’m a hardcore kid from Boston. They’re a hardcore label from Boston. They’re about a mile from my sister’s house and literally around the corner from Al Quint, who is from Suburban Voice zine.

One of the initial ideas was, do we just reprint all 20 issues? Hell, no. We said, “hat makes more sense? Let’s distill it down to a greatest hits. We’ll get it done in six months. No problem.”

Nope. As time went by, as I was getting quotes from people, it swelled into a different project, one that probably took us almost four years. It turned out to tell the story of music and ideology and ambition in motion.

We didn’t have the initial art for it so we were working from the actual printed zines. And some of those printed really well, and some of those, particularly the last few issues that were printed on newsprint, had the edges of words cut off, certain things didn’t print extremely well, there were certain design flaws.

Chris [Wrenn] went in and by hand, corrected some of the imperfections. So what you ended up with was actually something more coherent and more readable than the zine itself when it was printed in the ‘80s.

RF: What was it like re-interviewing artists for the book?

MG: There were some people who were very easy to contact, who came back with answers and with quotes, almost immediately. Perfect example: Henry Rollins. Literally, it took him 90 minutes to send me a quote back. I probably caught him on a slow day. Similarly, Ian McKaye, who I had known for decades now, was very quick to jump on the phone and talk about the ‘80s hardcore zines, and how those inspired him in a positive and a negative sense. There were also people who took upwards of a couple years to just hop on the phone, [like] Reed Mullin from COC [Corrosion of Conformity]. It took some time.

RF: I’ve heard that the Boston hardcore scene was the most violent in the country. Was that true?

MG: No. Look, Boston’s a hardscrabble town. Bostonians are by nature very direct, almost in a very European, sort of European sense. That straightforwardness can translate into aggression. You gotta remember that the early Boston hardcore scene–and I came a couple years into this–was just a handful of people. So it wasn’t this violent, wild mass. I mean there were some characters. You had Jake Phelps, who was a notorious slammer, Boston Crew alumni, now editor of Thrasher magazine. You had some larger than life people. You had people like the guys in SS Decontrol, you have people like Choke, who’s still one of hardcore’s most notorious button-pushers.

They had people like Al Burile, who propelled SS Decontrol from beginning to end, who was the boss, who was the guy who recorded the record that would be put on The Kids Will Have Their Say, and you hear that first crush of guitars, it’s the sound of liberation, you know what I mean? It’s a call to arms. That was Al’s brainchild, that was Al’s creation. You also had people who were very inclusive and welcoming and human, like Dave Smalley, who has completed that legacy from DYS to Dag Nasty to all, ultimately with Down By Law, some of his other projects.

As scenes grow, and other people come in, young people invariably have the need to prove themselves, and that can take the form of aggression. Los Angeles saw it years before, when Black Flag came up from the beach towns, from beach to beach, Redondo Beach and Lawndale, and brought surfers and skateboarders with them. And these were just naturally more aggressive athletic young men. They weren’t violent guys, they weren’t trying to hurt people. These were about young men in their own communities who had a communal bond. There were pig piles, there were kids letting off steam. But was it malicious, or intended? No. It was kids going off.

RF: I think that’s just kind of what goes with youth and growing up. Then they find this place where they can just be themselves.

MG: Yep. Exactly. You literally go to a show and you’re hearing music and seeing that just strike a physical and spiritual core like nothing else had before.

RF: Right. It just happened to be hardcore music.

MG: And it was also an excuse for you and your friends, who weren’t necessarily on the football team or the basketball team, who were not playing intramural sports, just to go off and to vent the frustrations that go along with being a young person.

RF: What kind of access did you have back then?

MG: Punk was the great democratization of rock and roll. It was the antidote to the arena and the light show and the rock star. We were all the rock stars. We all had something to say. Some of us wrote zines. Some of us put on shows and some of us picked up guitars and cranked up amps. And it was the day where you could go to the Channel and there’s Henry writing in his journal before a Black Flag show. You could go see Husker Du and there’d be Bob, Grant or Greg, just loping around waiting to play. You hung with some of your heroes. Because of the inclusive nature of any scene, there was really very rarely anything stopping you from walking up to someone with your tape recorder, going, “Hey, you got 15 minutes?”

It was very rare that an interview was set up in advance. The interview with Metallica was I think Issue number 10. They were at The Channel. There I was with my trusty tape recorder and as it turned out, Lars couldn’t make it into America. And I was walking up to Kirk, James, and Cliff and being like “Hey, let’s talk about punk. Let’s talk about punk’s influence on Metallica.” They were more than happy to oblige.

RF: You were talking about Dave Smalley and his eagerness to include new fans. Do you feel that people who wanted to find out more about the scene were welcomed in, or was it more like you had to know the right people to get in?

MG: You kind of had to go down a certain path of discovery. I’m from Boston. Luckily we had amazing commercial and college radio there. We had probably a good seven or eight college radio stations that had dedicated punk and hardcore programming. If you scroll left of the dial, you would tune into WERS or WZBC and sometimes you would land on a Black Flag song, or an early Birthday Party song. Or the Gun Club. Commercial radio in Boston wasn’t just playing REO Speedwagon, or Styx at that point. You started to hear, “Here’s ‘Rock the Casbah’ by The Clash, here’s ‘People Who Died’ by Jim Carroll,” so there was a new wave cresting over all of it.

RF: What was different about Boston bands like Void, Jerry’s Kids and SSD, that made them rise to the top?

GM: Quite often, the bands that don’t necessarily fit in are the ones that have the longest reach. They have the more difficult path. Musicians who take the more difficult path often are probably the most resonant. In the case of Jerry’s Kids, The Siege, they were doing their own sound. They were speaking with their own voice. And that to me, that’s the essence of, not just the essence of great punk or great hardcore, but great music in general.

RF: Looking back on it now, what were some of your favorite moments?

GM: When the first issue of xXx, came out [in June, 1983] there was a Dead Kennedys show at a hall in Waltham, which was Dead Kennedys, Jerry’s Kids, The Freeze And Proletariat. At that Dead Kennedys show, one of the first people who ever bought an issue of xXx from me in person, because I was selling them by hand at shows, was a young guy from Haverhill, Mass., a young guy who would later become known as Rob Zombie. Ian Mackaye and Jeff Nelson by The Channel in xXx Number 2. And DYS played their final shows as hardcore bands for that decade. That was a great moment. Seeing the Cro-Mags in New York and being just blown away. Just sheer force seeing a band that probably should have changed the world.

RF: Why do you say that?

MG: Because the Cro-Mags in 85, 86, those five people that were onstage were as explosive as any band you’d ever want to see. Those are five people who are completely like completely charged and completely combustible. And that translated to the music they made.

There were so many memories. I also booked a couple shows in the Boston area. Oh god, there were so many, early Descendants shows, early Rollins Band shows, Agnostic Front, Cro-Mags, to the Dag Nasty’s first Boston show, with Dave Smalley on vocals, just watching a band that was nothing short of inspiring and explosive.

That’s one of my key lines of the book: seeing a band back in ‘85 or ‘86 and watching how they affirmed and inspired people on an ethical, spiritual level. The values and the business practices that were inherent to Dischord Records or Touch and Go Records can now be felt in the mentality of artists like Shepard Fairey. The self-determination and self-actualization of punk and hardcore in the early ‘80s has really had a butterfly effect and ripple effect that not only extended to a musical level to things like Nirvana and Nevermind, which was the last great watershed moment in rock. But also echoes loudly in the culture itself.”

RF: Do you think younger fans look at these bands that got record deals and feel like they sold out? How do you reconcile with that?

MG: In the early ‘90s, specifically post-Nirvana Nevermind, a number of bands were signed to major labels, most of whom should probably have never signed to major labels. But a lot of bands got their shot, a lot of the bands made great music and had the resources to make great music. Jawbox, which was my friend J. Robbins, who I met when he was the bass player in Government Issue, I think probably made their best and most actualized records for Atlantic Records. I think that because they a little bit of a more promotional leg up, they were able to reach more people. And, consequently, probably their most challenging record, For Your Own Special Sweetheart, was heard by quite a number of people. I also signed Bad Religion, who were part of a movement of bands that always should have been, bands that had hit songs but just didn’t have the platform for those songs. It’s no surprise that bands like Green Day or Bad Religion or Social Distortion were able to have the commercial success via great songwriting. If you look at records like the Adolescents’ Blue Album, to me there’s some great commercial songs on that record that just didn’t have the platform to reach the audience that they should have. It’s only really been in the past couple decades that some of these bands have received that the acceptance and accolade that they really deserve. Adolescents’ “Amoeba.” “Amoeba” is a hit no matter how you slice it.

RF: It’s kind of making me think of Sex Pistols when they signed. They had some good music but then they couldn’t maintain it. It was just a mess.

MG: No. Sex Pistols were a great rock and roll band. I mean obviously neither you nor I were around when Never Mind the Bollocks came out. The Sex Pistols made a great rock and roll record. It’s just that they were such an alien and extreme concept that, they were more conceptually extreme than musically extreme. And like many bands they just sort of self-combusted because the people in the band, some of the major creative forces change.

RF: I guess some of it’s luck and some of it’s fate?

MG: Great art, that moment of inspiration, is what changes a person, it changes the world. At a certain point, I didn’t want to do Issue 21 because I had lost that sense of inspiration in 1988, because my life was changing, my career was changing. I was becoming a freelance journalist for a number of publications and I was in the process of moving from Boston to New York, so the inspiration and the moment changed. There was a reason why some of those bands didn’t last more than two or three years, because that moment of inspiration had passed and people were moving on. It’s why there’s no need for a Minor Threat reunion. There’s no need for an SS Decontrol reunion. That was that time, that was that place. I’m happy to see certain bands sort of continue and evolve to make music and to reach fans, but some things were so inspired and some moments were so inspired and so perfect that they can’t be recaptured.”