When Robert Plant sang of a modern Promised Land that was home to “a girl out there with love in her eyes and flowers in her hair” in Led Zeppelin’s iconic 1971 paean to decadence, “Going to California,” that place actually existed, and so did the girl (or at least her type). The place was Los Angeles’s Sunset Strip, the girls were called “groupies,” and they would impact on rock history their way… by creating some inspired music of their own.

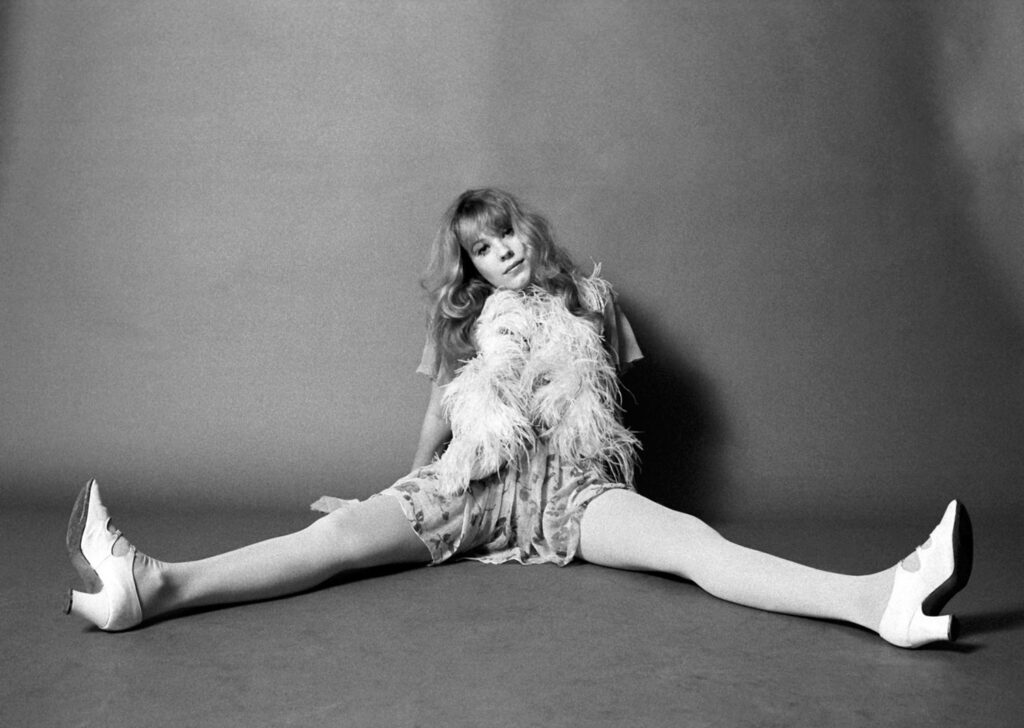

The groupie archetype borrowed its characteristics from the short-lived performance art rock group the GTOs, particularly band member and groupie mother supreme Pamela Des Barres. Hanging around her close friends Gram Parsons and Don Van Vliet (a.k.a. Captain Beefheart), Des Barres garnered the boys’ attention with her vintage silk dresses and feather boas, combined with her signature shaggy blonde hair that was usually adorned with wildflowers. Des Barres claims she first heard the term “groupie” in 1968 when she was called one after leaving a club with members of Led Zeppelin. She didn’t consider it a pejorative, but rather a welcome term for her place in the scene.

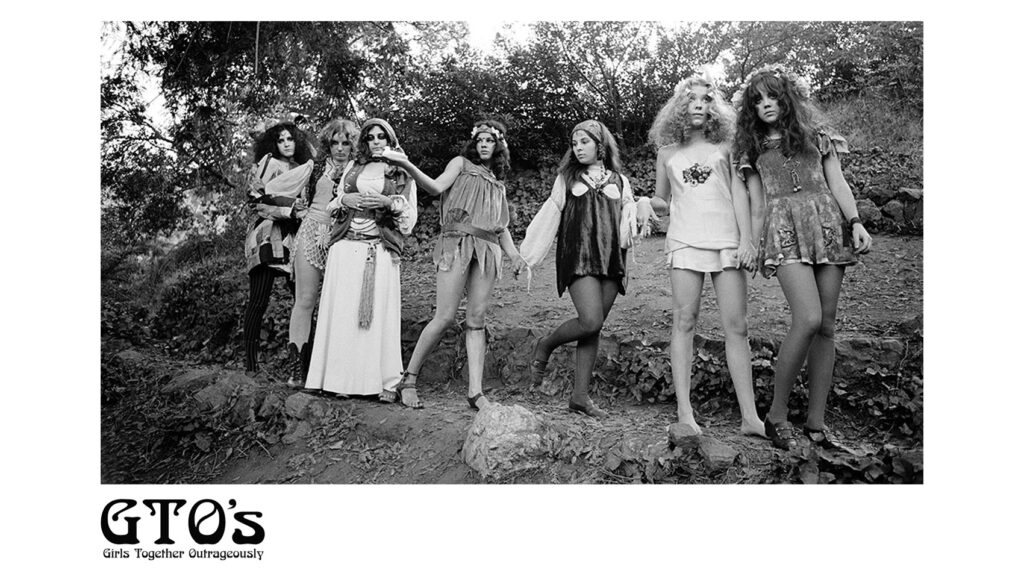

The band — which existed from 1968-1970 and whose name was an acronym for Girls Together Outrageously — comprised seven groupies, all of whom were fixtures of the fabled Whiskey a Go Go and Continental Hyatt House (or our preferred nomenclature, Riot House) scenes. The girls, each in their teens or early twenties, had been wrangled by their mutual friends Frank Zappa and his wife Gail to channel their collective creative energy into a unique performance art project. The band lasted a little over two years, releasing their only album, the Zappa-produced Permanent Damage, in 1969.

In the album’s liner notes, Mr. Zappa stated, “The GTOs write all their own lyrics, and no subject matter covered by these lyrics was suggested by any outside source. The choice of subjects is a reflection of the girls’ own attitudes toward their environment.” Featured are taped conversations between the band members, midwestern groupie grande dame Cynthia Plaster Caster (famous for making plaster casts out of musicians’, er, instruments with her sister), and the so-called “Mayor of the Sunset Strip,” Rodney Bingenheimer, each sprinkled like glitter throughout the gallimaufry of wonky pop-rock songs. Though the GTOs were the masterminds of the project, the album included contributions from the likes of Jeff Beck and a young Rod Stewart. Here, follow along:

The album opens with “The Eureka Springs Garbage Lady,” a vaguely medieval, off-key choral effort that leads into a conversation between Des Barres and Miss Sparky (née Linda Sue Parker) about stuffing their bras in high school. “It’s so great how we’ve turned from voluptuous high schoolers to flat-chested mini-mamas,” Sparky cracks. Permanent Damage is steeped in an acid-soaked sense of humor, like a aurally-pleasing R. Crumb cartoon. Another of Des Barres’ tracks, “Do Me in Once and I’ll Be Sad, Do Me in Twice and I’ll Know Better (Circular Circulation),” with its catchy chorus and sweet melody, could easily have been a minor hit if not for its inscrutable lyrics.

Aside from Des Barres, the most prominent personality in the band was undoubtedly Miss Mercy, whose wide-set face and proto-goth eyeliner made her look like a drugged out version of Theda Bara; and whose boisterous, unruly voice made her sound like a deranged version of Janis Joplin on the sensibly-named track, “I Have a Paintbrush in My Hand to Color a Triangle.” The album closes with Des Barres’ sugary pop ode to Steppenwolf’s Nick St. Nicholas, “I’m In Love With The Ooo-Ooo Man.” With hints like “His first name is the same as his last,” she announces her devotion and, at the song’s climax, exclaims what could essentially be the groupie mission statement: “Remember, girls, please don’t stop hoping! Never say your love is wasted! Love is only for giving! It’s something that cannot be taken!”

On the rare occasion that the GTOs are recalled in modern pop culture, they tend to be grouped alongside acts like the Shaggs — young girls who didn’t understand the music they were playing, while blissfully and more or less accidentally stumbling upon something great. Very few all-girl rock bands existed at the same time as the GTOs. Fanny, formed by the Manila-born, LA-based Mulligan sisters, was the first all-female rock band to release an album on a major label, but still remained relatively obscure throughout their career. The Runaways were still years away from proclaiming themselves the world’s wild girls.

Even if it didn’t reach many, Permanent Damage (with Frank Zappa’s seal of approval) afforded the GTOs the voice that free-spirited women of the late-60s were usually denied. Decades later, with the release of her 1987 book, I’m With The Band, Pamela Des Barres took the reins of her story and detailed her escapades — not all of them sexual — before, during, and after the GTOs. The book made the New York Times bestseller list and was described by Kirkus Reviews as a “classic account of rampant narcissism among guitar egomaniacs.” It told a side of the story that didn’t make it into Rolling Stone; Des Barres fawned over the music and, often, the musicians themselves, but she didn’t depict them as demigods. To her, they were deeply flawed men who abused their power, more often than not sleeping with young teenage groupies like Lori “Lightning” Mattix and Sable Starr.

I’m With The Band allowed Des Barres to reclaim her own narrative and opened the door for other promiscuous women to feel empowered to do so as well. Regarding the sense of duty she feels as a female storyteller, Des Barres says, “Very few women’s voices spoke from the 60s to early 70s music scene, and I’m proud to have been one of them. I consider myself a feminist and always have: a woman doing exactly what she wants to do… And getting away with it!” Despite this, the book was considered gossipy smut by many, and Des Barres regularly faced booing crowds when she appeared on talk shows. Chicago’s very own blowhard Mancow Muller once opened an interview with her on his radio show with the question, “How’s it feel to be the national slut?”

In a 2017 interview on Jezebel’s Dirtcast, Des Barres stated, “Everybody wants to be a rock star or be with a rock star, and whoever says they don’t is a liar.” It isn’t necessarily a gendered desire; the GTOs had their own groupies, some inevitably in the form of the dudes who hovered around them to get closer to Frank Zappa, but Des Barres considered most of them to be peers. By the 1980s and 90s, a new groupie led the charge on the Sunset Strip: Pleather, a straight male self-proclaimed groupie who claims to have slept with Courtney Love and all of L7. However, the term has almost exclusively been used pejoratively in reference to women.

The idea of a groupie doesn’t seem to exist anymore in its original sense; while there are certainly still fans who are rabid for the opportunity to spend a night with their favorite musician, it’s now a much more nebulous network, buried in the social media ether. The groupie scene of the 70s was characterized by a sense of community, documented by the short-lived Star magazine. The publication lasted for only five issues in 1973, going out of print after criticism of its coverage of the new generation of groupies like Starr and Mattix. The title of “groupie” started to lose its glamor when it became associated with teen girls living hard and fast, and was effectively killed when it transmogrified into VH1’s Rock of Love with Bret Michaels contestants.

The groupie culture that Des Barres was part of may not be around anymore, but thankfully the GTOs’ music is. Without it, we might only have the perspective of rock stars like Robert Plant who, for as culturally important as they are, only provided one side of the story. The GTOs had something to say and the talent to turn it into their own timeless music. The girls on the Sunset Strip had more than love in their eyes and flowers in their hair — they had their own place in musical history.

Pamela Des Barres; Photo Credit: Baron Wolman