“Amateurs sit and wait for inspiration,” Stephen King once wrote. “The rest of us just get up and go to work.” In that spirit, Riot Fest’s anthology series Autodiscography celebrates the tireless work ethic, versatility, and imagination required of our favorite prolific musicians.

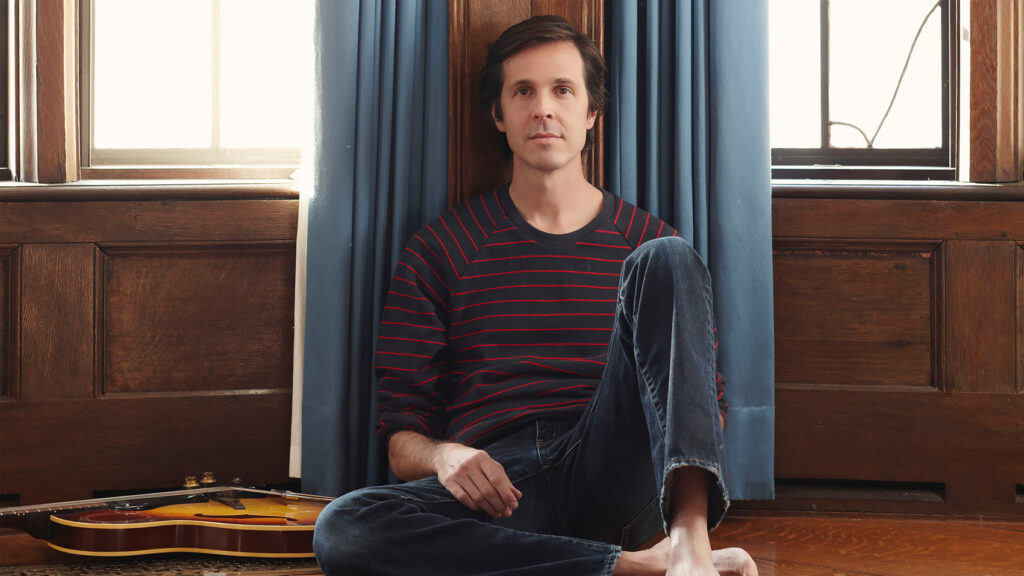

For today’s installment, we don’t feel the least bit ex-cre-men-ta-ble reviewing the life’s work of hardcore and post-hardcore legend Walter Schreifels. One would imagine the wizard behind Gorilla Biscuits, Quicksand, CIV, and Rival Schools — much less multiple recent projects that veer into blues, psych and folk — has very few unfulfilled dreams and visions after nearly 30 years in the business, but his self-described “workmanlike” approach resulted in three albums last year alone, including Quicksand’s long-awaited comeback, Interiors. We know you can’t wait one minute more to find out what drives the Rockaway Beach native to keep chewing out rhythms on his bubble gum, so start today. As in right this second.

THE RODENTS

RIOT FEST: You traveled a lot as a kid, from Rockaway Beach to Penn State and then Ohio before moving back to Rockaway at 10 or 11. Granted, this was before you started your first band, the Rodents, at 13, but did that itinerant upbringing have any influence on your eventual desire to be a touring musician?

WALTER SCHREIFELS: Maybe it did. I lived in a bunch of different places. Even in New York, I’ve lived all over the city, so it suits me to kind of be going to the next town. I had to start in different schools a lot, so I’m a quick study in a new environment. But I think for music, really catching onto it, I don’t know [that moving around had an influence]. I definitely caught onto music at a young age — I got into [my parents’] record collections, and it seemed to me that being in a band was the cool thing to do. I was into sports, but once I learned how to play guitar, I wasn’t interested in that anymore. I was just interested in playing in a band for, I think, the same reasons that most people get involved in it: to meet girls and have a cool time.

It’s interesting that you got into new wave stuff like Echo and the Bunnymen and the Smiths first, then the Ramones and the Who before diving completely into hardcore. This was the early ’80s, when diverse tastes were frowned upon between fans of heavy subgenres. Did you ever give or get shit in school?

I know what you mean: “If you’re into this kind of music, you’re not into that kind of music.” I guess I was more cherry-picking. When I was into stuff like the Smiths or Joy Division, I got into it randomly: listening to a radio station that was playing it. I heard it and it just hit me. I got the Joy Division album [Closer] as a gift when my mom went to England, just because it was popular at that time — I got that and a Police album. I wasn’t even sure if the band was called Closer or Joy Division.

Then there were bands I wanted to know about, like the Ramones or the Sex Pistols, that had sort of an ethos connected to them. I didn’t really understand what [the ethos] was about, and that was attractive to me. I had a denim jacket with AC/DC patches on it, and Led Zeppelin, which I guess gave me some cover to be interested in other sort of “off” things. But it wasn’t anything that I could be identified by, you know? I kind of felt that maybe happen more when I got into hardcore. I was sort of dressing… I went through a brief punk phase with the leather jacket and spiky hair, that kind of thing, but not so deeply that I was too picked on for it.

No music from the Rodents appears to be available online. Did you ever record anything with that band?

I don’t have anything in my possession, but my friend that I learned how to play guitar with, who was in the Rodents, does. He gave me a tape many years ago and I lost it, so I’m not gonna ask him again. [Laughs] But yeah, it was cool. There were some good, kind of punky songs. As I started to listen to hardcore, I was kind of aping the hardcore sound that I knew, which was not a whole lot.

What are your memories of playing out the first time: fear, excitement, all of the above?

Yeah! Rodents was more like, house parties. We were very young; it was a school thing. It was not a huge thing where we played a real club serving alcohol. The first time I ever did that was with Gorilla Biscuits at CB’s and I was crazy nervous. I had a hard time sleeping the night before, [but] I had a great time. It was ridiculous.

GORILLA BISCUITS | YOUTH OF TODAY | WARZONE

Did you have college or job aspirations in high school? When did you know you wanted to be a musician full-time?

My assumptions were that I would eventually go to college and figure out something that I was interested in to graduate, but I didn’t have any real ambition about it. I thought I might be a teacher or something where I would get a degree and someone would come to me for a job. [Laughs] I didn’t have any really great strategies about it. I guess I was thinking about what my parents did — they went to college and got jobs. I ended up not going my first semester of college because Youth of Today had a tour with the Adolescents, and I chose that. I ended up going back the next semester, but I think that kind of set the tone. Ultimately, when Quicksand went to a major label and I was paying my rent and didn’t have to work and I was living a lot nicer, then I started to think, “Well, I’m definitely not going to college now. If this all cools down, I’ll go back.” Then I think it wasn’t until much later — probably when I was in Rival Schools — that I said, “I think this is just what I do.”

Wow, that late?

Yeah, I wasn’t really thinking about my plan Bs too much after that. Maybe it’s the environment. Growing up in Rockaway, it wasn’t something you would think you would do: to be in a band and be a musician. It didn’t make any sense, really, especially doing it the way I was doing it, which was more like a workman’s way of doing it. I liked that part of it, actually; that’s what I’m the most comfortable with. The songs are inspired internally, and they manifest, then they get into other people’s heads, then I go around and play, and then I do it again. Then, I take that information and spin it again. I like that part of it: that honest, going-to-work part of it.

In Gorilla Biscuits, the arrangement was you wrote all the music and lyrics, and Civ [frontman Anthony Civarelli] sang. Did you ever have an epiphany about stepping up as a frontman?

I think after doing [1989’s] Start Today. I was initially singing for the band, but we needed a frontman — I couldn’t really play guitar and sing. That wasn’t the thing in hardcore. And Civ was the coolest guy that I knew. I asked him to do it, he was down, [so] ww started working out how we’re gonna make these songs. He has his way of singing that’s awesome, and we worked together to make that happen. I couldn’t sing those songs the way Civ sings them. It would be something else, at any rate. But in practicing, I made a vocal guide for Start Today. It was okay, it was good, but it made me think, “Okay, well, maybe I should just sing for a band so I don’t have to do this next-level process. Why don’t I just do my ideas straight?” So, I did a little project that didn’t really do too much called Moondog with the drummer of Gorilla Biscuits [Sammy Siegler].

You put out a third Quicksand album after a long hiatus. CIV’s Set Your Goals is more or less a third Gorilla Biscuits album. Can you ever see yourself writing new hardcore songs?

Between Quicksand and [blues/psych outfit] Dead Heavens right now, that’s really a lot for me. I sometimes think, “Yeah, it would be fun to do this or that.” Stylistically, there’s enough interest or audience that it would be fun and could be good, but for me right now, I’m just between the two bands that I have, and that’s plenty for me right now. I put out three albums last year with all different groups, so while it seemed like a good idea at the time, I wasn’t really able to promote the records to the level that I’d like to. You know, I want to stay prolific and keep moving, but… I think I’m good. [Laughs]

After you founded Gorilla Biscuits, you caught on with Warzone as a bassist. Were you only comfortable with guitar and bass at the time, or had you studied other instruments?

I didn’t really have any feeling about it in terms of bass to guitar. I thought it was just cool that I could do it. Especially because Warzone, at that time, represented the real shit. If you want to get into New York hardcore, that’s the place to learn about it. That’s the core. ’Cause Raybeez [Ray Barbieri] was there from the beginning. There’s so much to learn from him by what he told you and how he acted, or how people reacted to him. I had a sense of the music, and I had a belief that I knew where things could go and how things could fit. But being in that environment, it wasn’t like I was running the show — just being a good role player. The only reason I stopped doing that was because Youth of Today asked me to go on tour with them. Youth of Today at that time were my favorite band on the scene, so that was kind of like getting called up [to the majors]. Warzone were definitely a significant band, but Youth of Today were on another level already. It was a national thing, and Ray understood, Ray was cool about it.

MOONDOG

What was the consensus of friends and scene kids when you decided to do something different with Moondog, which eventually morphed into Quicksand? Was it hard to leave something as huge as Gorilla Biscuits behind?

I got a lot of great feedback, so that got me more confident to do something where I was the frontman. I followed that through to Quicksand. At the same time, I really loved working with Civ where I’m not the frontperson. That’s also a good position for me. [As for] Gorilla Biscuits, [we were] kind of popular at the time, but it wasn’t like us walking away from the Beatles. We were more friends than we were an operation. Arthur [Smilios, bass] had left the band — you know, it was a thing we were doing at the time as we were getting out of high school. Our lives were pointed in different ways.

For me, what was cool about Quicksand was that people outside of hardcore liked it. It had some other appeal, and that was what really drove it. Gorilla Biscuits was popular, but look at the old bills: We weren’t headlining all of our shows. We were able to tour around the country because we had a record out on Revelation. I wouldn’t even say we were big, but we were doing all right compared to bands that didn’t have that. Quicksand was a continuation. I didn’t see that being this huge thing, really. But because it had a wider appeal and all of a sudden major labels started to be interested in us, then I was like, “Okay, wow, I have to take this more seriously.”

QUICKSAND

You’ve mentioned at least a fleeting interest in Quicksand originally being a rap-metal project. Even though you’ve always had a rhythmic approach at the mic, it’s hard to envision that, knowing what rap-metal is now.

Yeah, it’s kind of funny to talk about it in a way, but also you have to take the context of the time. All hardcore kids were listening to hip-hop. You would follow it as closely as you would hardcore — you know, what sneakers were cool and so on. This was really just a New York thing. I mean, of course, other cities had hip-hop, but it just didn’t sound good… at all. It sounded like they didn’t get it. You can see how it affected the New York hardcore scene in terms of how demo covers looked, how T-shirts looked, and how graffiti was connected to it.

Of course. You were listening to Public Enemy and De La Soul. It’s not like a band coming out today who was influenced by, like, just Korn.

I was never really into metal. I got into Metallica and Slayer after hardcore, and after new wave. I wanted to be punk; I did not want to be metal. I didn’t think metal was cool. It was only afterwards, after Master of Puppets and Ride the Lightning or Reign in Blood [that] I had to admit, “Damn, these things are just great.” But I knew I’d never get much deeper with quote-unquote metal, all that orthodoxy that people are super stoked on. I can appreciate it, but that wasn’t what I was into. Through those [Metallica and Slayer] records, I realized there was power in a big heavy metal riff. There’s a certain power in Public Enemy that, if you’re spewing some righteous shit over a metal riff and it’s convincing, you can move people. It just works. So, we were kind of playing with that at first.

Was it hard to tap back into that with Interiors?

Yeah, it’s fucking hard. With the new Quicksand album now, I think it’s heavy, but I don’t think there’s, like, violence to it. I can admire Slayer or Deftones — things on that level — but I don’t really feel that way. Or if I do feel that way, it’s not something that I want to do for a living: those kind of vocals. It’s not what naturally calls me. We get along really well these days. We’re kind of beyond trying to fit in with one thing or the other. We’re more into finding what we feel moves us and relying on that.

You’ve had so many repeat collaborators. Which one would you say “gets you” the most?

I couldn’t really say one person above the others, but I think there’s a special chemistry in Quicksand because the voices are so distinct. Sergio [Vega, bass] and Alan [Cage, drummer] and I are such dominating types of people in some ways [musically]. We’re not passive people; we’re all full of ideas. When you have three people that are full of ideas, sometimes it’s hard to make anything work. The fact that we’re able to makes it a really powerful combination. I think Dead Heavens, we have an excellent chemistry. We get to the same idea very quickly and no one has to try that hard to make anything happen. If I wanted to make a hardcore record, I would want to call up Luke Abbey — he’s the best. Sam Siegler is amazing, too.

Why was the 1998 reunion tour — opening for Deftones — the first time that your interest in heavy music waned?

I mean, when I was playing in Gorilla Biscuits, we had some good mosh parts, but it wasn’t the Cro-Mags. Or Quicksand — we have some heaviness, but it wasn’t like… I remember hearing Deftones for the first time, and the first chord of [“My Own Summer (Shove It)”] on Around the Fur. The screaming and the power of it, I thought, “I’m out of this business. I can’t go there. [Laughs] If that’s what being heavy is now, forget it.” That just knocked me out in a way.

I think it’s awesome and I totally appreciate it, but that’s not really where I wanted to go. I didn’t want to make people necessarily, like, mosh and have that kind of experience anymore. I wanted to do something different. Things I’d been expressing in CIV or World’s Fastest Car or my solo work, I felt we were outgunned in that world. We needed to find a new way of doing it. I don’t know if I was right about that.

Quicksand’s lone Hollywood appearance was in Empire Records, in which Renée Zellweger gyrates in nothing but an apron and her underwear to “Thorn in My Side.” Thoughts?

I’ve never seen Empire Records, but I think it’s probably the best film of the ’90s.

WORLD’S FASTEST CAR

When Quicksand originally dissolved in 1995, you gave post-hardcore another shot in the very short-lived World’s Fastest Car. Why were the only WFC shows in Japan, of all places?

We actually had a show booked at CB’s, but we cancelled it. We played in Philly the night before and the show was so awful. We fell apart, really. Our drummer didn’t know the songs. It was really crazy. There were a lot of reasons for it. I don’t know if that was before or after Japan. Over there, we felt really comfortable to just do whatever. We played great, actually. But we got back and the band did not rehearse well enough. We just kind of blew it, and it fell apart from there.

I think there were a lot of great songs, though, and some of them found their way into Rival Schools. “Used for Glue” was a World’s Fastest Car song, “Everything Has Its Point” was a World’s Fastest Car song. “Requiem,” which never really got released in a good way until my solo record [2010’s An Open Letter to the Scene]. That also had to do with my status at the record label. I was being put in one of those holding pens that they put you in at major labels, and that just fucked with it, too.

Any new information on formal releases of Moondog and World’s Fastest Car, much less whatever Walter and the Motorcycles is? Is your Wikipedia page up to date with your increasingly long list of unreleased work?

Oh no, that’s another job I gotta get on, making sure that shit is tight. [Walter and the Motorcycles], so many things are just placeholder names and that was me not knowing what I was gonna do next, if I was gonna make a solo record or name it something, so I was fucking with that. That was after Rival Schools. “Am I gonna make a solo record? No one knows how to pronounce my last name — is that a good idea?” My unreleased stuff ends up on the internet anyway. There’s definitely stuff that hasn’t been released, but I’m at peace with that problem.

CIV

During the Quicksand years, you once again wrote music and lyrics for Civ on CIV’s Set Your Goals. Was it easier this time since you already had an outlet as a frontman?

Yeah. It let me get back into my hardcore writing, but also my more current interests. I didn’t want to call it Gorilla Biscuits because I wanted to have the freedom to do new stuff and be funnier in some ways. People who are really into hardcore have a real ownership of the group, and if the band veers off the path, however slightly, they can be totally wrecked for it in the scene. So, putting it in a different context allowed me to have fun with it. Also, the people I was working with on the record were my best friends, so the vibe was just really good. That came through on the first album — the second album [Thirteen Day Getaway] I was not involved with except for one song. At that same time, Quicksand was very heavy, so it was nice to have something that wasn’t heavy.

Out of all your projects, what’s the video that pairs the best with a specific single?

Definitely “Can’t Wait One Minute More” is the best. We made the video ourselves and it got on MTV, like on Buzz Bin. It was a really cool video, but also crappy production-wise. It was perfectly crappy. That was when the talk show people like Jerry Springer and all that kind of shit were really popping off, so it was commenting… nowadays if something is happening, people are commenting on it through memes, like right away. Back then, it was a little slower reaction time, but we were pretty on it. The song was cool — the video really sold it to the record label because at that time, MTV was everything.

RIVAL SCHOOLS

You’ve been on the periphery of two zeitgeist moments, once with Quicksand in the “next Nirvana” gold rush, and then with Rival Schools, during the third-wave emo explosion. Although associating the latter with emo seemed odd at the time.

It was odd in a way, but a lot of the emo bands [at the time] were inspired by Quicksand in some ways, from the Get Up Kids to Dashboard Confessional through Jimmy Eat World; because we were hardcore, yet [had] these emo-y vocals.

[Skeptical] I guess.

I mean, I only know it from these bands telling me. So, when Rival Schools came out and all these bands were coming up at the same time, we got shoehorned in with them… which is fine. In England and in Europe, and Australia as well — everywhere but the United States, because the record company didn’t really push us in the United States — in the places we did get pushed, we did very well. I don’t think anyone in those bands was like, “Yeah, we’re emo, man! We’re gonna emo you out!” I think they were all just like, “Jesus Christ, don’t call us that.” It’s just a way to package this group of bands, and we were being included in that, and it meant that more people were going to listen to us. I wasn’t going to fight it. To me, emo is Rites of Spring, Embrace. And I’m influenced by that stuff. That comes through. [Laughs] So, as much as it’s bullshit, it’s also fair.

Do you feel like it took a while for your fans to rectify your past in hardcore and post-hardcore with your more pop sensibilities?

Probably for some people. Quicksand had a hardness to it that Rival Schools didn’t. So, that’s understandable. Some people aren’t going to follow, but some other people are. You never know who’s going to connect to it in the context in which it comes out: who hears it, who says it’s good, who doesn’t care. Sometimes it really all clicks. More often, you only check one box: It’s really good, but no one cares. It’s not that good, but the record company did a good job, so everyone cares. [For me] it’s more about my own relationship to the music. Some of my best stuff, in my opinion, is not really what necessarily connects to the widest group of people. And I’ve learned to live with that. And then some things I don’t think are very good at all or really hit the mark will connect with people, and I gotta go, “Fuck! Why is that?”

Care to give an example of that?

The Moondog thing: I only hear the imperfections in it. I can’t listen to that, really, and other people love it. I accept it and I’m totally happy that they do, because if they heard it like I heard it, they’d be like, “Damn, how did that get out?” In this case, it’s kind of a happy accident.

WALKING CONCERT/VANISHING LIFE/DEAD HEAVENS

Your catalog is so diverse. Do you think the majority of your fans have followed you on a through line for all 30 years? Or are there, say, newer, younger Walking Concert or Dead Heavens fans who are into indie-pop or psych and don’t know shit about Gorilla Biscuits?

Oh, it’s more the second. There’s definitely a group of heads that [make up] probably a 10 or 15 percent overall through line. But most Gorilla Biscuits fans don’t know who Quicksand is. [Pause] I shouldn’t say most, but less than 15 percent. Quicksand to Gorilla Biscuits is probably even less. And Rival Schools is another. The crossover there, you gotta be into it to follow that shit. I don’t know if I could do a survey, but the person who knows that I did Rival Schools, Quicksand, CIV, Youth of Today… I don’t think most people get that. They’re just looking at the name of the band; they’re not necessarily following the personnel or giving a shit who writes the songs.

You might be being a little modest in that regard.

Yeah, maybe. I hope I’m wrong. That would be cool. But I know there are people following all of it intensely, and that’s awesome!

You’ve put out three albums on Dine Alone — your solo album An Open Letter to the Scene in 2010, Vanishing Life’s Surveillance in 2016, and Dead Heavens’ Whatever Witch You Are in 2017. Obviously, the label is named after a Quicksand song. Were you tight with Joel Carriere when he launched the label in 2005 or is this all a happy coincidence? Did he ask your permission to use the name?

Oh yeah, he asked me for permission, which was very cool. He didn’t have to. It’s not like I would’ve tried to sue him or anything. I consider it just cool, you know, that someone would want to take something that I’ve done and reappropriate it. It’s awesome. But yeah, I was on a tour with Walking Concert — we were opening for Eagles of Death Metal and Joel came to the show. He didn’t know the opening band, but he recognized me, and after the show he came to talk to me and told me that he was a fan. At that time, he was just doing a management company and promotions. We became friends and he invited me up to Canada just to hang. When he started the record label, he asked me, “Hey, is it cool if I name it Dine Alone?” And I was like, “Yeah, dude. Rock. That’s great!” The real awesome thing is how successful he’s been. To be associated with something that is not only successful, but it’s coming from a guy who’s real with the people in his town [Toronto]. Dine Alone definitely punches very far above its weight. The bones of the company are comprised of music fans, so it’s built from a real solid foundation.

Quicksand, Gorilla Biscuits, Vanishing Life, and Dead Heavens are all active in some capacity, right? Is that the max for you, four bands at the same time? Do I hear five?

[Laughs] It must have been. I think the most I ever was in… at one point, I believe I was in Supertouch, Gorilla Biscuits, and playing drums in a band called Good and Plenty. We didn’t do too much with that. I’ve always [had] two or three different projects kind of cooking. There have really only been a couple of periods where I was just in one band. I think that’s what I learned from hardcore: You’re kind of jumping in different things, picking up different stuff, getting inspired. And that inspiration carries over to the next thing. I’m really proud of the Vanishing Life record, for example, but we just haven’t had the opportunity to play that much. That becomes the issue. But in terms of making the record or the creative process, it’s awesome. And I feed off of that. Having done the Vanishing Life record, it put me more into position to make the Quicksand record [Interiors]. I wanted to feel that kind of aggressive side of things. And, you know, Dead Heavens got me in the zone, in some ways, to get Vanishing Life. They’re all feeding each other in some ways.

PRODUCING/THE FUTURE

Out of everything you’ve produced, from Hot Water Music to Title Fight and beyond, what was your most fulfilling experience?

Well, I’m usually not pushing any buttons or anything like that. I’m more like a coach in a way. I’ll get in on a musical level and just kind of see where they’re at and try to encourage the things that I think would make it better. I try to keep people energized. It’s like when you’re bowling or something and you roll a strike, everything feels loose in your body and it’s just like [makes pins crashing sound]. And you try to imitate that naturalness, and it just ends up like 6s and 8s and 9s. There’s something about that looseness that allows people to do awesome things.

It’s so cool to play with Hot Water Music. While I’m working with them, I’m picking up their vibes, too, and learning what is great about them and feeding that. I really enjoy it. I don’t engineer, so I guess I don’t do it that much. I should’ve been doing it in the ’90s more — it would be a better career. Title Fight you mentioned as well — they’re great. They were very young when I worked with them, but for not having a lot of experience, they also knew a lot intuitively. A lot of producers come in and think they know the answer to shit. I just never take their approach. A producer has to be someone that you can respect and whose aesthetic you can appreciate; and somebody you can cooperate with and defer to in moments of doubt.

With your 50th birthday a couple years away, is any part of you starting to think about slowing down?

I definitely am surprised by how much I want to do. I keep thinking, “I’ll do this record and then I’ll just kind of chill,” but I just keep thinking of more shit that I want to do. And I’m comforted by that — that I still have a drive in music and also other things. Like, I’m housebreaking a puppy. Like, I want to do this right, among other things. But no, I’m excited. I don’t want to get older any faster, but I feel really cool to have been doing basically what I would be doing anyway and had an opportunity to develop as a person through music. I can look back on so many points in my life and have some sound indication of what was going on, what I was into, what I was feeling good about, what was bugging me. I don’t think it’s that deep, but a lot of people need to find a function, and not everyone gets to. I feel lucky that I have that.