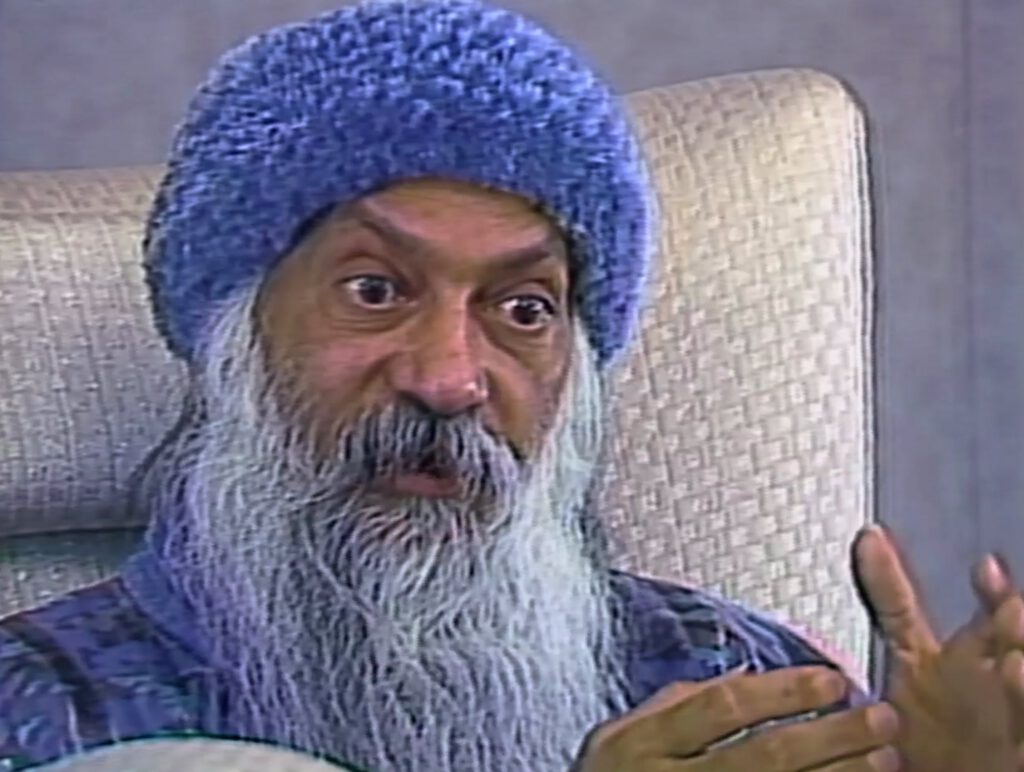

With Wild Wild Country, their new documentary series for Netflix, filmmaker brothers Maclain and Chapman Way dive deep into the story of Rajneeshpuram, a controversial religious community founded in rural Oregon in the early 1980s. From the outset, the provincial ranchers in the nearby town of Antelope were uncomfortable with the presence of guru Bhagwan Shree Rajneesh (known later as Osho) and his free-loving, red-wearing, mystic hangers-on, but after the local government tried to exploit state land use laws to push the Rajneeshees out of the county, tensions began to boil over… ultimately leading to immigration fraud, election manipulation, bioterrorism, and violence.

It’s an often-lurid story with plenty of potential for sensationalism, but as they did with their debut film Battered Bastards of Baseball, the Way brothers imbue Wild Wild Country with humanity and a great deal of empathy for all its subjects. Despite this, the heavier subject matter lends the series a tone more in line with the latter-day work of Errol Morris (minus that filmmaker’s sometimes-combative interview style) than with their scrappy, lighthearted debut.

Even if you know the story, you’ll be hard put to look away from this telling of it. We recently met up with the Way brothers at a coffee shop in Los Angeles to discuss the series, the separation of church and state, and what it was like to interview someone who’d been described by Oregonian ranchers and government officials alike as “pure evil.”

RIOT FEST: A lot of the residents of Antelope, Oregon who made it through the Rajneeshpuram debacle felt traumatized by the events covered in Wild Wild Country. Did that make the initial interviews challenging?

MACLAIN WAY: I think so, yeah. We always knew that getting the Sannyasins on board to speak about it would be challenging, but I was surprised — though in hindsight, I shouldn’t have been — that ranchers and Antelopians were also hesitant to talk. I think both sides saw Rajneeshpuram as a warning, though of course they saw it as two: the Rajneeshees saw it as a warning about the persecution of minority religious groups, whereas Antelopians saw it as a warning about the danger of cults and brainwashing.

So, both sides felt this push and pull regarding whether they wanted this story to stay forgotten, or if they were interested in engaging. Ultimately, both sides decided that they didn’t want this story to remain in the dustbin of history, and we’re really thankful for that. We wouldn’t really have a documentary series were it not for the individuals that were willing to talk with us on camera about something that was painful and traumatic for both sides.

Did you use any tactics to maintain a journalistic even-handedness?

CHAPMAN WAY: People have told us we did a good job of showing both sides, but to be honest, that wasn’t from a morally righteous, ethical journalistic position. In fact, I tend to get frustrated with documentaries that get stalled in counterargument and lose momentum!

This story, though, is inherently about two sides. We took both the Sannyasins and the Eastern Oregonians at their word about their experiences, so we were walking a cinematic/narrative tightrope: How do you make it so the viewer is invested in each side’s respective journeys, where you’re asking them to invest in one side, then completely pivot and get invested in the other side? Once we started experimenting with that in the editing room, though, we found that it created this huge sense of tension and intrigue.

MW: If you just Google Rajneeshpuram and read up on it, there’s really not much debate about the facts of what happened. We basically know what happened out there — in terms of the crimes and all that — so we knew we didn’t want to do a true crime Whodunit? thing.

There’s not a lot of room for debate! We know the Rajneeshees put salmonella in salad bars, we know there were attempted murders and immigration fraud. For us, what was really fascinating were the justifications people used to get to that point.

Image Courtesy of Netflix

Was it intimidating to interview [Rajneesh’s fiery, controversial personal secretary] Ma Anand Sheela at first?

CW: Yes. The first thing we did with this film was get access to these 300 hours or so of footage from Rajneeshpuram, which had never been transferred and was just sitting on these tapes inside the Oregon Historical Society. When we started transferring the footage, Sheela was the first character that obviously stood out: she’s captivating, terrifying, smart… basically everything you’d look for in a character.

When we first reached out to her for interviews, we assumed that there was no way she’d want to do it, but it was pretty clear after initial talks that she was just as feisty and opinionated as ever, and she didn’t feel like she’d ever been given a platform to explain her side of things. We told her we weren’t interested in an interrogation or a Gotcha! interview; so we went to Switzerland and sat with her for five days and had a real conversation.

Sometimes we’d challenge her on things, sometimes we’d just let her go; but in the end we ended up with an incredible interview, because she felt confident enough to revisit that time and explain everything from her perspective.

MW: To a lot of the Oregonians we interviewed, Sheela was just pure evil. One of the federal prosecutors literally said as much in his interview, and I don’t think he was trying to spin it or anything. That was just the feeling a lot of these people had. So, going to her was really interesting.

Image Courtesy of Netflix

On the first day of interviews, she wasn’t really laying stakes in the story, and was treating it all as this thing that happened such a long time ago. She’d moved on. It wasn’t until we showed her some of our archival footage that that quiet rage started to come back. I think she’d really pushed it out of her mind before. From then on, she really laid into explaining what happened from her perspective.

CW: Yeah, we’d been hearing that she’s pure evil, but when we first came to her house — and y’know, these first meetings are always hard, especially when you’ve heard so much about a subject for 18 months before ever meeting them — it was the day after Trump was elected, and the first thing out of her mouth was her just roasting us about American culture and politics.

MW: She gave us a ton of shit.

CW: It was really charming and funny. Then, she gave us a tour of her house, and she’s this incredible artist; someone who’d studied at Montclair State University and lived this hippie-bougie lifestyle in New Jersey during the Summer of Love. Plus, she’s a big cinephile who loves Fellini movies and what have you.

So, we immediately had to reconcile this version of Sheela, this elderly woman running a health facility for disabled people, with this person that government officials had called pure evil. We knew that, if we could tap into that dichotomy, it would be a really good challenge to the audience.

The two primary groups in Wild Wild Country, painted with the broadest brush, are conservative rural Americans and cult members, both groups that are hard to get middle-of-the-road audiences to empathize with. In your minds, what did you do to help facilitate that empathy?

CW: I think it was less manipulation on our part, and more just our actual experience with these subjects. The first thing we heard from the Antelope people is that the Rajneeshees were all just brainwashed cult members, but the ones we met were highly intelligent and successful people who’d just gotten burnt out and joined this movement for meditation and love. They were fully consenting adults who knew exactly what they were doing. It may not be your belief system or mine, but if theirs is weird, then every religious belief system is weird! We didn’t see them as brainwashed at all, even if it’s not a group I’d personally join.

Conversely, though, the Rajneeshees would talk about these Antelopians as this one-dimensional stereotype, as a bunch of old bigots and racists. When we went there, there were all kinds of people: libertarians, extremists, anarchists, conservatives. What tied them together was this little community, which they loved being a part of even though they were all different.

Actually, it was interesting how similar both sides were: on one side, you have these frontier people who built their own town, with their own church in the middle of town where they all worship, their own saloon, schools where they teach Christian theology. Then, you have the Rajneeshees, who just wanted their version of the same thing on their ranch. When people think cults, they think of communes and, by extension, communism, but the Rajneeshees subscribed to a spiritual belief that was pure capitalism. They were basically libertarians, but definitely neither side could really see the other as similar.

Right. It’s more a difference of aesthetics than anything else.

CW: Exactly.

MW: Roger Ebert once called TV and film “the empathy machine,” and I fundamentally agree with that. When you see people on camera — when you see their — there’s a psychological impulse to empathize with them.

In addition to that, though, there’s craft to it: if you listen to the score, Wild Wild Country is kind of scored from the perspective of the person telling the story, and we didn’t make a practice of undercutting anyone with that. They might not feel that way, or they might feel undercut by other interviewees, but it was at least our intent in how we structured it.

CW: There are a lot of misconceptions about scores for documentaries, whereas some people think they’re too manipulative and designed by the directors to make you feel a certain way. Really, what we do is pay attention to how the subject feels about something, and score it from their point of view. It’s not us telling you something is scary or whatever. We just want to drop you in and have you follow the journey of these characters and how they feel. That allows people to feel more empathy, because you’re experiencing the story from these different perspectives.

MW: Right. Like, in Antelope, are there elements of bigotry, racism, rednecks going on? Yes, there are elements of that. Honestly, we could have found people who would’ve said way more awful shit about the Rajneeshees on camera than anyone we interviewed. I was more interested in talking to someone like John Silvertooth, who was willing to talk at length about this in somewhat of a nuanced way. That doesn’t mean he didn’t say anything in the series that made me cringe, but he’d also say things like, “Do you know what it’s like to try to raise a family in this town, then all of a sudden you look outside and people in red with semi-automatic weapons are walking around in your front yard?” I’d have to concede that no, I didn’t know what that was like.

Every side had their stories, though. Just wearing red in Oregon, even in Portland, back then…

CW: One Sannyasin told us this story, which we didn’t include, where he was walking through Portland in his red, and people were just shouting at him to “go back where he came from,” and he was born and raised in Oregon! There was awful treatment on both sides, and that’s a big part of the story.

MW: I don’t want to sound pedantic, but I just hope this series makes audiences think critically about the issue. I’m just as bad as anyone else, y’know? If I read something in the news, I’ll have a knee jerk reaction where one side is good, and the other side is bad people who are fucking up America.

With Rajneeshpuram, a lot of people don’t know the story, so they’ll come to it on the fence and see these two entrenched groups that are uncompromising, and not really know who’s right and wrong. It definitely doesn’t fall easily on a left/right political divide, because the Rajneeshees are these kinda liberal-minded people who are also are into the second amendment and armed to the teeth, and the people of Antelope were these frontier folk; but you can still sympathize with what they went through, too. In the end, I hope it’s not easy for the audience to take sides.

CW: As soon as we started diving in, the clear subject of Wild Wild Country became the separation of church and state. It truly is a two-sided coin: we don’t want religion controlling our government, and most Americans agree with that, but there’s also the concern of government intruding into religion. More than anything in recent American history, this story just cuts right to the heart of that debate. We all like to think of ourselves as being very tolerant of others, but I think this series forces you to say where you personally draw the line. Where does someone’s right to personal religious freedom intrude on someone else’s? There aren’t black and white answers.