By the beginning of 1993, it was obvious that rap music was the next big thing. The hot streak of massive, radio-devouring smash rap songs that had kicked off a couple years prior with MC Hammer’s “2 Legit to Quit” didn’t seem to be ending. Exciting new rap acts were popping up in every corner of the country, from Atlanta to California; and with an entire wave of alt-rockers emulating Nirvana’s anti-cool stance, there weren’t many commercially-oriented rock bands looking to give them much competition. Even the most skeptical label execs and radio programmers were starting to admit that it seemed like this hip-hop thing might not be a fad after all.

The hip-hop boom was already transforming radio, clubs, and the teen magazines that had started slotting in Vanilla Ice and Kriss Kross alongside the usual range of New Kids on the Block knockoffs. Rap was clearly establishing its hold on the pop zeitgeist; the big question on the music industry’s mind was how they’d get diehard rock consumers – especially the ones driving that big, lucrative alternative rock boom – to turn into rap fans. Some of the attempts at making that happen were comically delusional. I remember getting an alt-rock sampler tape around that time with a Shaggy song posted hopefully alongside a bunch of Replacements knockoffs in the apparent hope that his vaguely exotic air would resonate.

The prevailing theory was that the hip-hop act that would break through with the alternative rockers was the one that sounded and felt most like alternative rock, whether it was a metal-rap hybrid like Ice-T’s Body Count project or the hippie-dipped psychedelia of Arrested Development or PM Dawn. Fewer people expected that rap would find its way into Gen X’s heart in a cloud of weed smoke and gangster paranoia.

Fewer people expected that rap would find its way into Gen X’s heart in a cloud of weed smoke and gangster paranoia.

Granted, not a lot of people expected Cypress Hill’s Black Sunday to do the things it did. Rap’s rise was driven by clean cut bubblegum, with a side order of crunchy granola stuff like Arrested Development to prove to the aging hippies at the wheel of the industry that the genre was capable of seriousness. Industry executives were so convinced that the future of hip-hop was in an army of Kriss Kross clones that even as undeniable an instant classic as “Nuthin’ But a G Thang” came as a surprise to them. On paper, the audience for a grimy platter of nasally vocals and obscure jazz samples driven by unhealthy obsessions with weed smoking and gun violence seemed miniscule at best.

B-Real, DJ Muggs, and Sen Dog’s masterpiece, however, resonated with a massive audience across the entire spectrum of popular music, from the most hardcore reaches of hip-hop to the Top 40. Nowhere did it resonate as much as in the alternative rock movement. Black Sunday doesn’t have any of the amp-shredding power chords or slam-poetry introspection that labels were sure alt-rockers wanted out of a rap group, but it quickly became part of the cultural conversation on the left end of the dial alongside the Jesus Lizard and Tool. It wasn’t uncommon to see Cypress Hill on dubbed tapes as the flipside to Nirvana or – even funnier, considering the content – Fugazi. “Insane In the Brain” got played on alternative radio, and when they toured with Lollapalooza in ‘94 they played near the top of the bill, not in a freak show slot as the token rap act.

On the surface, Cypress Hill and its new alt-rock fanbase seemed like on odd pairing. As the more verite moments of Black Sunday make clear, the group’s members grew up in a world far apart from the bland suburbia that alt-rock drew its angsty inspiration from. But a lot of B-Real’s lyrics turned out to be surprisingly relatable to Gen X-ers. Obviously, at a time where stoner culture was first starting to reemerge after the Reagan years, there was a hungry audience for weed anthems. But there was a deeper level of the lyrics that spoke to the same kind of themes that rock had been drawn to post-Kurt Cobain: inner turmoil, paranoia, existential rage. In the pre-Columbine days, singing along to an ode to assault rifles felt like a healthy way to vent whatever pent-up anger you might be carrying around.

Musically, Black Sunday was as far out as anything getting played on 120 Minutes. The vinyl collection that DJ Muggs cut up to create its beats reads like a crash course in key movements that every good record geek should know: psych rock, vintage soul, free jazz. He sampled Chicago soul legend Syl Johnson and California avant-pop icon Harry Nilsson a decade before they were “rediscovered” by hipsters in the aughts. There wasn’t anything on earth that sounded like Cypress Hill. There’s a reason why things clicked so well when they linked up with Sonic Youth on the otherwise iffy alt-rock/hip-hop hybrid Judgement Night soundtrack: they were probably the two most innovative bands putting out big records at the time in any genre.

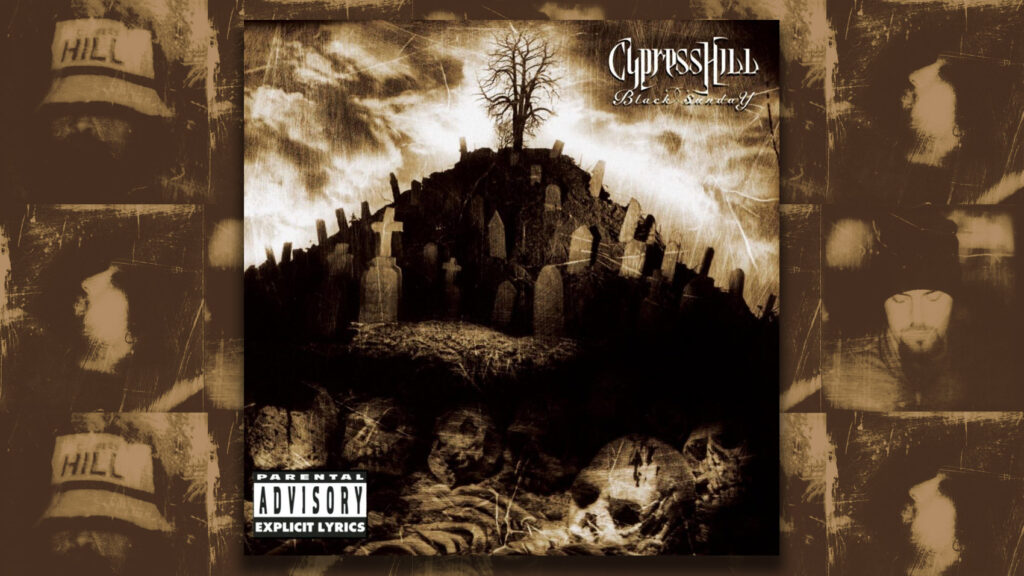

On top of that, they had a gloomy skulls-and-smoke visual aesthetic that connected with alt-rock sensibilities in a way that Dr. Dre never could. There was a minute where Cypress Hill was the only acceptable rap music that you could like and still consider yourself goth.

Looking back at it now, Black Sunday seems to have more in common with the bands Cypress Hill played alongside at Lollapalooza ‘94 than the smoothly menacing g-funk acts that radio and MTV were trying to lump them in with at the time. Ever since then, it’s been a touchstone for musicians trying to tap into a feeling of dark, hazy paranoia, a state of unsettling psychedelia that Cypress Hill perfected with the album—not just for rappers, but for electronic musicians and rock bands of every stripe. What began as an oddball album for a niche audience and became an unexpected crossover hit has become one of the most influential albums of the alternative era.