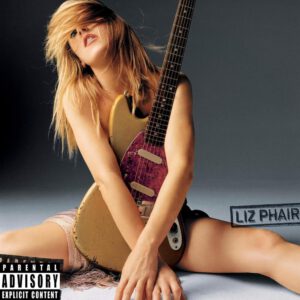

The first Liz Phair song I ever loved was “Rock Me” from her 2003 self-titled album. My best friend at the time had included it on a mix CD she made me when we were both ten years old. The song features Phair pleading a guy almost ten years younger than her to rock her all night, pairing perfectly with the album’s sexed-up cover: Phair, hair tousled, shielded by her guitar, wearing no more than a nude slip. To a fifth grader, she embodied everything a woman could be —everything I desperately wanted to be. I hoarded the track in my iTunes library as if it were a Playboy under my bed.

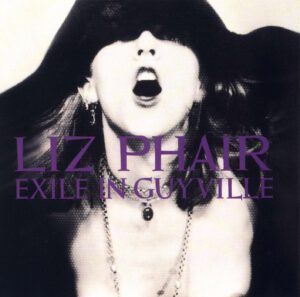

Years later in high school, like so many other girls coming of age post-1993, I rediscovered Phair through her debut album Exile In Guyville and her Girlysound tapes. They were shocking in their honesty, and I don’t think it’s hyperbolic for me to say that they were life-changing. What really rocked me to my core, though, was finally realizing that her self-titled album that I had once loved so deeply was almost universally reviled.

To be anyone other than a straight white man in indie music is to essentially always be on the verge of exile. That’s not revelatory; everyone knows that one slip up for a ‘cool girl’ can send them to the frozen tundra of alleged poserdom. But it’s impossible to talk about Liz Phair’s career without bringing up this cliché. Exile (which turned 25 earlier this year) proved to be both a reclamation of her own alienation from Wicker Park’s dude-centric indie scene and a prophecy for her virtual banishment from alt-rock once her music began trending towards pop.

With Exile, Phair articulated women’s sexual desires and grievances in a way that had previously been confined to girls-only spaces. She wanted the things that women weren’t supposed to want—or at least, not publicly or explicitly—and she wanted them from men who couldn’t give less of a shit about her. The fact that she voiced seemingly conflicting desires to take some random guy home and “make him like it,” and want all that stupid old shit like letters and sodas, was revolutionary. As Exile’s 33 ⅓ author Gina Arnold puts it, “Phair may have undermined the male ego, but she also unleashed a new female one.” Unsurprisingly, the album was a hit critically and, to a modest extent, commercially.

Phair’s tenure as indie’s latest it girl was relatively short. Her next album, Whip-Smart, while beloved in its own right, couldn’t live up to the hype Exile wrought. The album was more polished, and thematically she seemed a little more inhibited. The album’s opener, “Chopsticks,” features Phair absently talk-singing about a one night stand, but unlike the climactic Exile song “Fuck and Run,” she dwells on the awkward moments and closes with “I dropped him off and drove on home because secretly I’m timid.” The album did well critically, but never attained the otherworldly success of her debut. Whip-Smart seemed destined to be the start of a never ending sophomore slump.

Each of Phair’s subsequent releases became increasingly less well-received, to say the least. Her third album, Whitechocolatespaceegg, passed by without much notice. She’d gotten married and had a kid, and started to tackle topics other than Rainbo Club-induced one night stands. With the shift in tone, the horny dude critics who had once revered Exile (and the raunchier parts of Whip-Smart) dipped out quicker than the guys Phair may or may not have written about.

Her 2003 self-titled album managed to get close to the amount of recognition that Exile had, but for all the wrong reasons. Phair returned to the honest raunch that had won people over on Exile, but this time, she was someone’s divorced mom; if the gatekeepers of Guyville had scoffed at her writing about settling down and starting a family, they sure as hell didn’t want to hear about her playing Xbox with her decade-younger boy toy. The album received a soul-shattering 0.0 on Pitchfork, and she became what the New York Times referred to as a “piñata for critics”. As I think that Dark Knight quote goes: you either die an indie girl, or you live long enough to see yourself become “vapid” and “overdetermined.”

Her 2003 self-titled album managed to get close to the amount of recognition that Exile had, but for all the wrong reasons. Phair returned to the honest raunch that had won people over on Exile, but this time, she was someone’s divorced mom; if the gatekeepers of Guyville had scoffed at her writing about settling down and starting a family, they sure as hell didn’t want to hear about her playing Xbox with her decade-younger boy toy. The album received a soul-shattering 0.0 on Pitchfork, and she became what the New York Times referred to as a “piñata for critics”. As I think that Dark Knight quote goes: you either die an indie girl, or you live long enough to see yourself become “vapid” and “overdetermined.”

Maybe songs about sex as a divorced mom aren’t as “hot” as her Exile material, but they’re just as brutally honest. People don’t like to see women they consider ‘cool girls’ grow up into a more traditional version of womanhood; it’s no coincidence that after having a kid and dominating every rom-com soundtrack of the 2000s, everyone suddenly thought she was washed up. Liz Phair wasn’t the comeback album that so many of her fans wanted, and it maybe wasn’t even what Phair herself wanted, but it’s an undeniably solid pop album. I don’t know how my friend found the album as a ten-year-old. We lost touch nearly a decade ago, so I can’t ask. I guess it feels fitting, though, that it’ll always remain something of a dirty secret between girl friends.