To kick off our new zine interview series, we talked to Portland-based zine-maker and creative powerhouse Sarah Mirk. A former editor and podcast host for Bitch Media, she’s now an editor at the political comics site The Nib. She’s the author of the relationship guidebook Sex from Scratch: Making Your Own Relationship Rules and the sci-fi graphic novel Open Earth. While we talked, she folded zines.

RIOT FEST: Let’s start by talking about your 365-zines-in-365-days project.

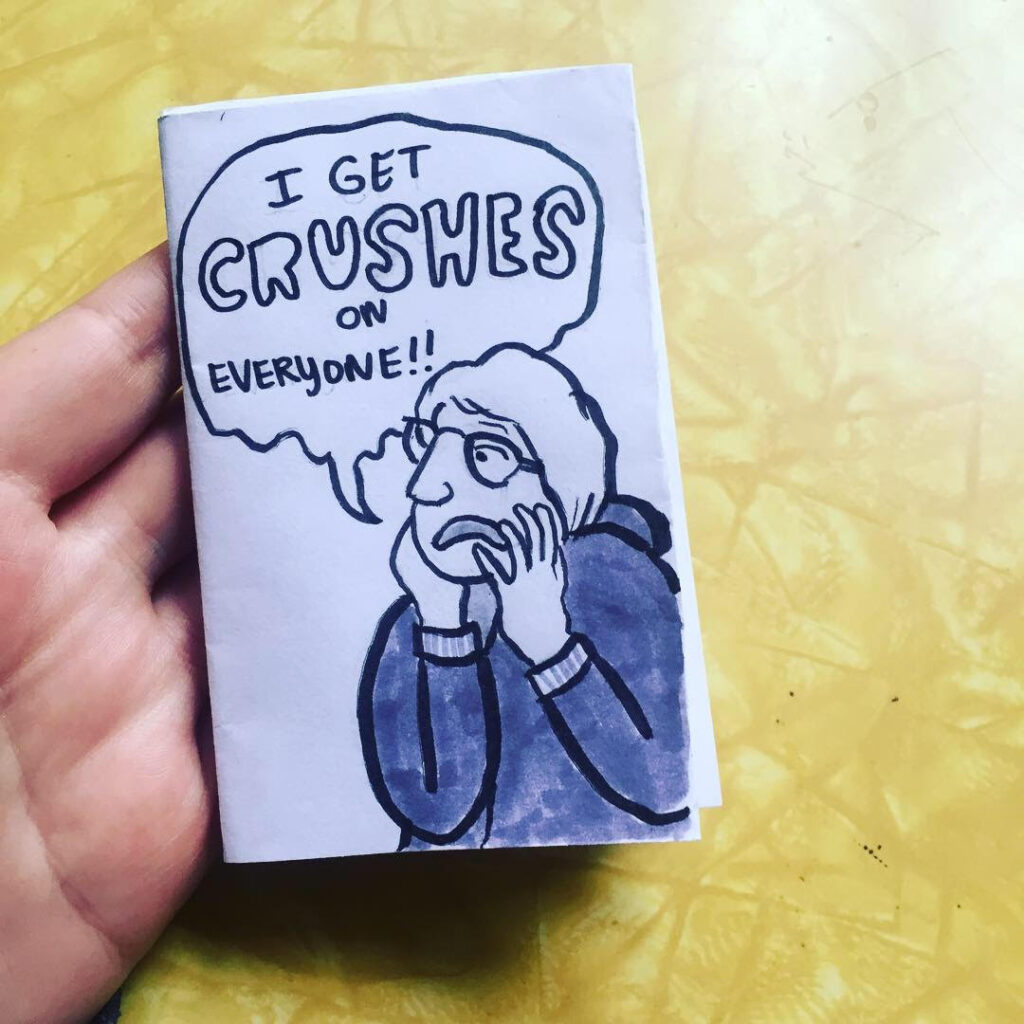

SARAH MIRK: So, in 2019 I’m making a zine every day. Which mostly just seemed like a fun challenge. I started in Inktober, which is this thing that happens among illustrators and comics artists where during October people challenge themselves to make a piece of art every day. So I thought, “Okay, I’ll make a zine every day.” And I loved it. I got to the end of the month, and I was like, “Oh, I could easily come up with a hundred ideas for zines. What if I pushed myself to come up with 365 ideas for zines?”

But also, it’s really nice to make something to share every day, and to feel like, at least I accomplished this—and I can put it out there. I work as an editor at The Nib, and there my job is pretty behind the scenes; I help people with their scripts, I help people pitch and shape their stories. But when it’s published, it doesn’t have my name on it. It has the name of the writer and the name of the illustrator, but the editor’s job is so invisible. So to counter that, I wanted to do a project that was more visible. I can put my name on it, and every day I publish something.

Also, I’m working on a book that’s going to come out in 2020. It’s an oral history of Guantanamo Bay, which is pretty dark. I’m spending a lot of time talking to people about really traumatic stuff and really complicated politics. I wanted to do something that I could share before 2020. One of the big challenges of working on a book is that you’re not going to share it with people for years—it’s taking over your brain and all-consuming, but there’s nothing to show for it. I can’t take screenshots of my transcriptions, or take a photo of me talking on the phone every day and be like, “Look guys, I’m working!” [laughs] So I wanted to make something I could share that would keep me going during a really difficult long-term project.

Do you sometimes have to squeeze the zines into your days in interesting ways?

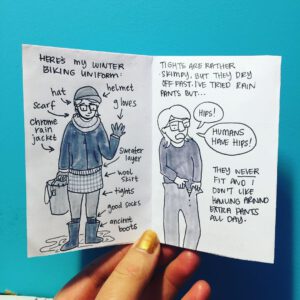

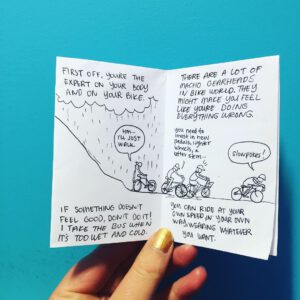

Oh yeah. So, the kind of zines I’m making are one piece of paper that’s folded to make a cover, back cover, and six pages. The reason I use that format is that it’s very portable and easy to do. I always carry with me a blank piece of paper that’s folded into the format and a package of pens and pencils. So no matter where I am, I can get started on that day’s zine. I make zines during meetings at work, I make zines on the bus, and basically any time when I’m like, “Okay, I’ve got half an hour before I have to meet this person. I’ll get there early and start working on this zine.”

I’m always thinking about what the zine is going to be for that day, and then when I get time I start pencilling it out. Then in the next chunk of time I start inking it, and then I erase the pencil, and I can photograph it.

How do you decide which ones you photocopy and which ones you just post online?

I copy them all—and that’s one part of why the format needs to be consistent. Because at the end of the month, I run them through a photocopier and then I fold those up and send them out to the people who back me on Patreon. So, some people [who] subscribe get a “zine of the month club”—they get one or two every month—and some people get all thirty. I sometimes don’t have paper on me, and I end up using some random sheet of paper that’s a different size, which screws me up at the end of the month when I need to photocopy—I can photocopy 28 at a time, and then there’s two weird ones.

The genius thing about this one-page-folded format is that this costs me five cents to duplicate, so at the end of the month I make 90 zines and it’s $4.50. For under five bucks I can fulfill all these orders. So the format is driven by economy—not having much money to spend on this project—and portability. I need to be able to do it anywhere.

Even outside of the zine-a-day project, you have a different approach to making zines than a lot of people do. You often make them for specific events, or make them to be gifted rather than sold. What’s your relationship to zine-making?

I love being practical and I love being productive, and I see zines as very useful. That’s why I like to make zines that always have a purpose. For example, last year I was living in Philly, and when I was leaving Philly I wanted to make something for the friends I’d made there. So I was like, oh, I can make them the gift of a zine about my year here. For my thirtieth birthday, I made a zine about my twenties—thirty lessons from my twenties—and that was a gift I could give out at my thirtieth birthday party to everybody who came. It was also, for me, a useful way to reflect on that time.

So you’re right, I really see them as practical and kind of productivity-oriented. But not in a way that’s tied to finances. When I hear the word “productivity,” I think, oh, that’s a corporate idea about making money, but instead I just mean that I like making stuff that people can use. Zines are really good for that.

What are some examples of zines you’ve made as part of this project that fit into that idea?

The most clear one is I’m making a zine for my brother’s wedding. My brother’s getting married in May, so I made a zine for all the guests at the wedding to have a map of the town where he’s getting married—which is my hometown—food suggestions, places to eat, places to hike, and weird local history. So we can give that to all the wedding guests and they can have a little guide to the city while they’re there.

Basically any political organization that I like that asks me to make a zine, I’ll make them one for free. I made one for the Philly chapter of the Democratic Socialists of America’s feminist group—which exists because the DSA can be a very bro-y organization. They asked me to make a zine for an event they were doing, so I made one about why I’m a socialist. And it happened to be right after Trump’s State of the Union where he really ragged on socialism, so it was nice to be like, “Okay, here’s what socialism actually is. Here’s why I’m a proud socialist.” And now this group can give it away at their events.

I also made one for an organization in Portland that’s trying to stop the expansion of a freeway project here. The zine’s called Stop Building Freeways, and it’s about the problems of that project in particular and then the larger issue of building freeways in urban spaces in the United States in general. The group printed 150 copies of that and gave it away at a meeting where people were giving public testimony to the transportation department. To me, that’s a very practical way to share information. You could just as easily give someone a URL to read a website, but who’s going to follow that? It feels different when it’s in print—it feels more special and more immediate. Like, somebody gave this to me, so I’m going to actually read it.

What I love about zines is that they’re obviously made by hand. They’re obviously made by a person, and I think that really comes through for readers. It’s not just a bullet-pointed manifesto about freeways that’s anonymously posted online. It feels like a human being thought about this and made this object, and now it’s come into my hands.

You exist in a lot of worlds—you’re a comics editor, book author, zine maker, journalist—do the amount of roles you’re playing ever feel overwhelming?

I definitely feel like my career would be better if I was more focused. [laughs] But I’m just naturally curious about a lot of different things and like to make work in a lot of different mediums. That’s just the way I am, and the way my brain works. I don’t understand how someone could be a writer who just writes about, like, transportation. One topic. How do you do that? I would get so bored. Sometimes stories just feel like a better fit for a particular medium. I think it’s really cool that I can tell some stories in book form, that I can tell some stories in online comics form, and I can tell some stories in zine form. It just depends on what the story is.

Serious journalists often don’t allow themselves to work in other mediums, because they think no one will take them seriously if they make comics or write fiction. But I don’t think that’s true; I think people are multifaceted, they’re interested in all different types of things. You should allow yourself to make work in all different types of ways.

As a zinester and comics artist, do you have any thoughts about the similar-but-different zine and comics cultures?

SM: Well, the comics world is really big. There are people who are interested in it for all different types of reasons and are interested in all different types of stuff. So if you go to a comics festival, there’s going to be people there who are really into Marvel and DC and superheroes, or who want to figure out how to be screenwriters.

You more know what to expect when you go to a zine festival. It’s going to be a lot of scrappy people who are making their work for passion, not profit.

I take zines with me whenever I travel, because I always try to find the zine shops or the people who are making zines. Two years ago when I was in South America, every city I went to I was just like, “Hey, do you know where I can find zines?” Everywhere there’s people making zines. I remember in this one town in Chile, I was asking, “Do you know anyone who makes things like this?” [holds up a zine] and they were like, “Oh yeah, there’s some young people that sell them in the plaza in the evening.” So, in the evening in the central plaza, these teen punks spread out a blanket and sell their zines on this blanket. There’s no zine store. There’s no kind of infrastructure like that. But even then, there’s people making them and selling them.

Sarah’s book Guantánamo Voices will be out fall of 2020 on Abrams Books. You can follow her zine-a-day project on Instagram and Twitter. You can support the project through Patreon.