In our series Punk Rock Movie Night, we handpick two precious gems from the vast and mysterious world of “punk rock films” for your household to enjoy while self-quarantining. Get some snacks—we’re gonna have a TV party tonight. What, you got something better to do?

Throughout most of North America in the late 1970s and 1980s, the punk underground really had to cobble together its local show and touring systems from scratch. The audience for underground music in any given town was pretty small, and most established clubs and theaters wouldn’t have anything to do with it. Since it was rare for punk shows to happen in traditional venues, it was particularly hard for touring bands to figure out where to play: in the pre-internet days, tours were booked by poring over fanzines and scene reports in Maximum RockNRoll to garner even the foggiest notion of where the kids were. Unless you had a friend in a given town already, you basically cast your fate to the wind, keeping your fingers crossed all the while that the people booking your show weren’t crypto-Nazis or something (it’s not for nothing that Green Room was an especially visceral scare for seasoned touring musicians).

It was a challenging time, but of course, we’re living in a whole other set of challenging times. Now that countless people worldwide are hunkered down in a pandemic scare, the two films I’m going to talk about today spark a surprising feeling of longing. It’s a rare situation that makes me wish I was crammed like a sardine in an old school bus, surrounded by the sweat and farts of a bunch of stinky dudes, but at least those guys weren’t afraid of catching the fucking plague.

Watching footage of basement shows conjures up a similar set of emotions. Usually, if I were to get misty-eyed thinking about punk houses, it would be from the overwhelming sense-memory of garlic-and-unwashed-nutsack B.O. Living in quarantine, though, even that’s a little missed. (A LITTLE.) Honestly, I fully expect that we’re all going to be pretty wistful for the stench of our friends by the end of this thing.

![]()

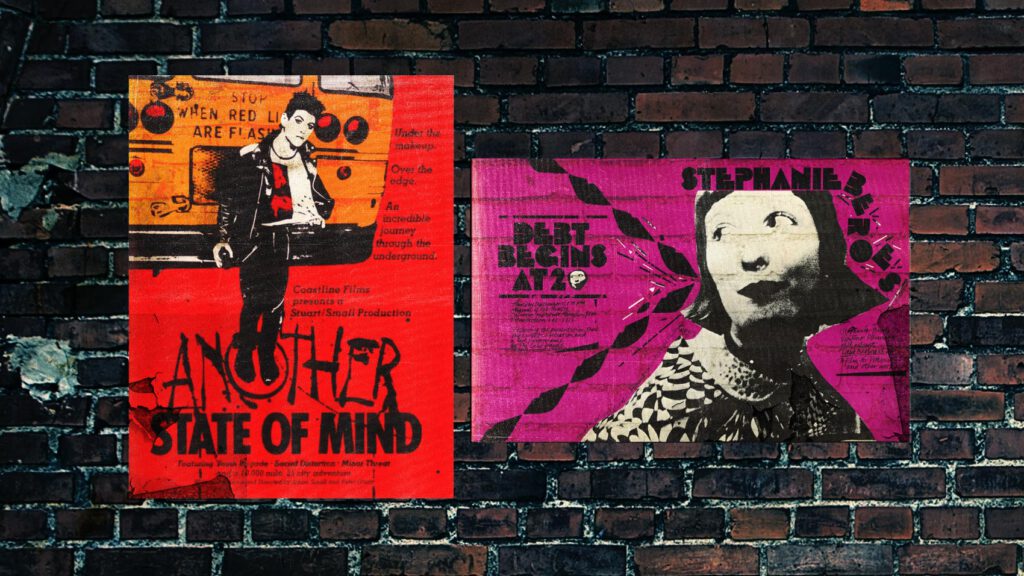

ANOTHER STATE OF MIND (1984)

Social Distortion are a Riot Fest favorite (one of the 15 all-time favorites, actually), and they’ve been a known and respected commodity for forever. As such, it’s kinda hard to imagine them as a scrappy young band playing DIY shows and touring with subsistence level per diems. Lucky for us, we don’t have to imagine: someone caught a few of those days on film, and the result is a quintessential portrait of no-budget punk tourdom.

In Another State of Mind, Social Distortion pairs up with fellow SoCal punks Youth Brigade (not be confused with the DC hardcore band of the same name and time period), a trio of brothers who’ve cobbled together money to buy an old school bus for their first tour. They’re a ragtag crew with a lot of strong personalities: Youth Brigade vocalist Shawn Stern, more or less the film’s central character, is the earnest “community organizer” type. He helped to found the Better Youth Organization, and planned this tour all in hopes of fostering a more positive image of punk.

Social Distortion frontman Mike Ness, meanwhile, is already driven and ambitious, image-conscious and strategic in most every move (save some fun, silly footage of him utterly trashed during one show, but even that could be chalked up to mythmaking). Side crew like “rock star roadie” Mike Brinson, whose hair is dyed different colors in different local bathrooms throughout the film, is clearly just there for the party, and is quick to duck out when the going gets rough.

And the going does, indeed, get rough. The bands get denied money by shifty promoters; roadies defect and take the Greyhound home when the bus starts having trouble. In New York, the crew even ends up crashing at P.U.N.X. House, run by a Christian organization called Patriots Of Jesus Christ who works to spirit kids away from the punk life and into the arms of the Lord.

The bus finally dies as the band rolls into Washington DC, leaving most of the crew to stay at Dischord House with Minor Threat for several days (this section yields some of my favorite footage of the film: Ian MacKaye working his day job scooping ice cream at Häagen-Dazs). In the film’s climax, the bus gets abandoned, with Stern and the remaining diehards riding across the country in the back of a moving truck.

If this all sounds familiar, it’s because this is basically what happens to any punk band who goes on tour with no label backing, very little money, and questionable transportation. Still, if it’s a story which makes one question why anybody who put themselves through all this, it’s also one that is incredibly relatable to anyone who’s done it. Cruddy as it may’ve felt at the time, I’d bet dollars to donuts that Mike Ness doesn’t regret that disastrous first tour now, and you won’t regret watching him do it.

![]()

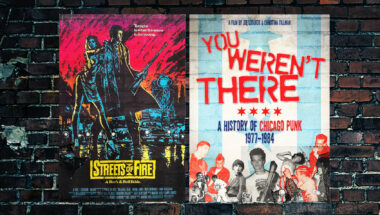

DEBT BEGINS AT 20 (1980)

Pittsburgh is a long way from Southern California, and if Stephanie Beroes’ classic short film Debt Begins at 20 is to be believed, their early local punk scene was also a far cry from the nascent hardcore scene documented in Another State of Mind. Documented in gritty black and white 16mm, the bands that populate the Steel City basement shows documented herein—The Cardboards, Hans Brinker and the Dykes, The Snakes—seem largely uninterested in hardcore’s loud/fast rules, having absorbed the lessons of both UK bands like X-Ray Spex and west coast synthoids The Screamers and Tuxedomoon. They’re noisy, sloppy, and willfully obtuse,with nary a trace of hardcore—or even the Ramones—to be found in their approach.

The wildest thing about the scene documented here, though, is just how much it looks exactly like those of today. The sounds, fashions, attitudes, and even lyrical concerns are nigh-identical to what they’d be now; Hans Brinker and the Dykes, in particular, are proto-riot grrrls with lyrics about getting a hysterectomy to avoid bringing a kid into this rotten world. Of course, part of that continuation also has to do with the fact that this film is particularly influential in Pittsburgh, so much so that local stalwarts the Gotobeds paid tribute to it in the title of their most recent record, Debt Begins At 30.

As a film, Debt Begins at 20 is also artier than most punk films made outside of New York City at this time. Beroes is largely identified as an experimental feminist filmmaker, and her other work around this time is somewhat akin to that of peers like Barbara Hammer and Shirley Clarke. That said, this film in particular also readily recalls the enfants terrible of the French New Wave: its blending of documentary, raw dramatic footage, and snotty attitude definitely has a whiff of early Godard, but even more the caustic work of obscuro “filmmaker’s filmmaker” Luc Moullet (if the name rings a bell, you probably heard of him from former Chicago Reader critic and Moullet superfan Jonathan Rosenbaum).

This is all to acknowledge that Debt Begins at 20 is perhaps a bit more high-falutin’ than some punk films, but that designation does little to take away from its primordial oomph. In our modern sea of sanitized VH1-style documentaries, all canonizing the same 10 bands who supposedly “revolutionized music” instead of talking about how punk upended the stadium-rock hierarchy, Debt Begins at 20 still stands out because it gets into the real nitty-gritty of documenting how an actual punk scene functioned in its community then, and how they more or less continue to function to this day.

Another State of Mind is available on DVD, but a little hard to track down for a reasonable price. For now, though, it’s on Youtube. Debt Begins at 20 can also be watched for free on the website to the film’s UK distributor Lux, or as part of Ears, Eyes & Throats, a really great collection of restored punk films featured on one of this writer’s favorite websites, byNWR.