Keith Morris’ abrupt departure from Black Flag at the end of 1979 came as a shock to everyone around him; few would realize it was a gift in disguise until the Circle Jerks came together before the end of the year. For everything Morris brought to the table with Black Flag, he now could set his own thresholds for his explosive energy and searing wit. With the combined fury of former Redd Kross guitarist Greg Hetson, classically-trained bassist Roger Rogerson, and jazz drummer Lucky Lehrer, the sky was the limit.

Group Sex, released 40 years ago today, is one of the best descriptions available of the American punk landscape circa-1980: raucous, loaded with sarcastic disdain for authority, and totally unpredictable. For all the (well-aged) verbal rampage against superficiality and authoritarianism, there’s just as much on binge drinking and vasectomies. In the case of Circle Jerks, the willingness to go either direction—or neither, in favor of tempo-bending, ear-splitting chaos—is why Group Sex remains so entertaining today. Its quick and to-the-point design is what allows 16 tracks to burst with innovation in fifteen-and-a-half minutes in length. It’s remained a landmark release in hardcore punk for four decades as a result.

For the 40th anniversary of Group Sex, I spoke to founding members Keith Morris and Greg Hetson—along with Frontier Records founder Lisa Fancher, Decline of Western Civilization director Penelope Spheeris, and legendary punk photographer Edward Colver—about the band’s swift beginnings, how the album was collaboratively stitched together, and how Decline would help fast track widespread appreciation for the Circle Jerks.

![]()

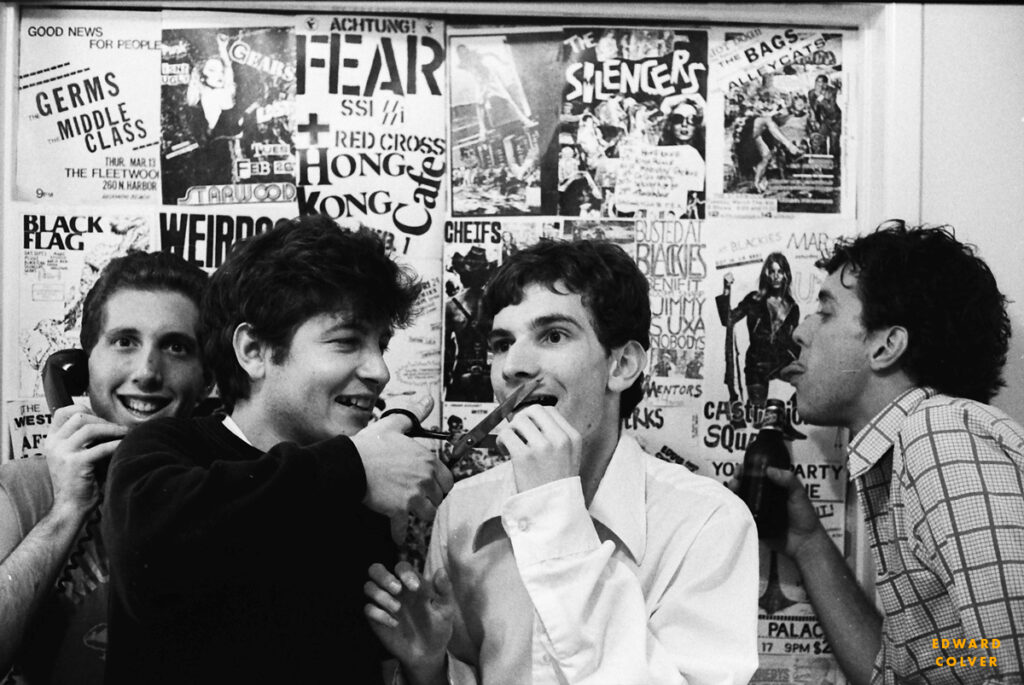

THE BEGINNING OF THE CIRCLE JERKS

Just a month after Morris abruptly quit Black Flag, the gears were already turning on a new project. Originally called the Bedwetters, the Circle Jerks would form in 1979 when Morris joined forces with guitarist Greg Hetson, who’d also just called it quits with his band Redd Kross (spelled Red Cross at the time, before a hefty lawsuit). The lineup would quickly fill out with Lucky Lehrer on drums and Roger Rogerson on bass.

GREG HETSON, GUITAR: Keith and I met because I was playing with Redd Kross and we had Black Flag’s Nervous Breakdown record. We were looking at the liner notes like kids would do, and we saw “P.O. Box 1, Lawndale, California.” We were living in Hawthorne, California, which is just the next suburb over, and would go after school and stop at the post office in Lawndale hoping we would meet Black Flag… ‘cause we had no idea how to get gigs. Eventually we found out where they rehearsed in Hermosa Beach and went down there and just said, “We’re in a band, can you help us out?” That’s how I met Keith.

KEITH MORRIS, VOCALS: The way Black Flag’s practice space worked is that if you wanted to come and hang out, you were more than welcome to. And I encouraged everybody to bring along a couple of six packs with them. That was certainly going to allow you entrance.

HETSON: He was drunk most of the time. All the guys in Black Flag and Keith especially were very cool, trying to help a young band out. “We’ll help you get gigs. We’ll help you play some parties with us.” This and that. They guided [Redd Kross] on how to be in a band.

MORRIS: I had just quit Black Flag maybe a month earlier when Circle Jerks began. It could have been less. I was just drifting about. I was the wandering Jew. I had nothing going on. My schedule was wide open.

HETSON: I was playing with Redd Kross only for a bit when our drummer had quit. I was friends with Chet Lehrer, Lucky’s brother who ended up forming Wasted Youth, and eventually he goes, “My brother’s just graduated college. He’s moving down back to L.A., he’s a great drummer, you should check him out for Redd Kross.”

MORRIS: Now remember, I was a drunk. I could be wasted at noon on a Sunday afternoon. I could be out of my mind. But the way that I remember it is that they held an audition for Lucky in the basement of the church where Black Flag rehearsed Redd Kross rehearsed there for a while—it was also Ron Reyes’ bachelor pad. I’m sitting in the hallway in the basement in front of the door to where they’re playing, and the door comes flying open. The first two guys to come out are Greg and Lucky, and they’re looking at each other; they’re disappointed. Greg thought it sounded great, Lucky thought it sounded great, but the McDonald brothers weren’t into it.

HETSON: To make a long story short, they kept making excuses why they didn’t wanna practice with the guy, and I got frustrated and quit the band.

MORRIS: They apparently didn’t like Lucky Lehrer and the fact that he was so proficient on drums. Like, he’d actually played drums since he was 10 or 11 years old, and actually studied big band and jazz drummers. Anyways, the McDonald brothers didn’t like Lucky, and Lucky is not going to be the drummer in Redd Kross.

HETSON: The way I remember quitting the band is that I was standing out in front of the Whisky a Go Go, waiting to go in, We were supposed to practice that day, but I said, “Fuck it, we’re not practicing. I’m going to a gig.” I ran into Keith and started hanging out front with him, and who strolls up but Jeff and Steve McDonald. They go, “I thought you were too sick to practice.” I was like, “I’m sick of this bullshit. Fuck you, I quit.” And what I remember is Keith saying, “Fuck this guy. Let’s start our own band.”

MORRIS: The three of us looked at each other and one of us said, “We have a drummer, we have a guitar player, a vocalist. Now all we need is a bass player.” And that would happen a couple of weeks later. I was sitting against a brick wall attending some show at one of the clubs on Melrose, my bottle wrapped in a paper bag. I’m enjoying it. I look up and there’s this goofy looking fellow who’s just kind of hovering over me. I said, “So who are you?” “Oh, my name is Roger.” “Oh, okay. So what do you do?” We get into just a simple, very easy conversation. And as it turns out, Roger’s a bass player. And that’s when the light bulb went off over my head. “If you’re a bass player, would you like to play in a band that I’m getting ready to play in?” I explained to him Circle Jerks, and he said, “Well, heck yeah.” And that’s how all of that started. I reached up my bag with the beer in it and let him take a couple of swigs. He thanked me and he said, “Yeah, we should be in a band.” And that’s how that all started. Just that simple.

![]()

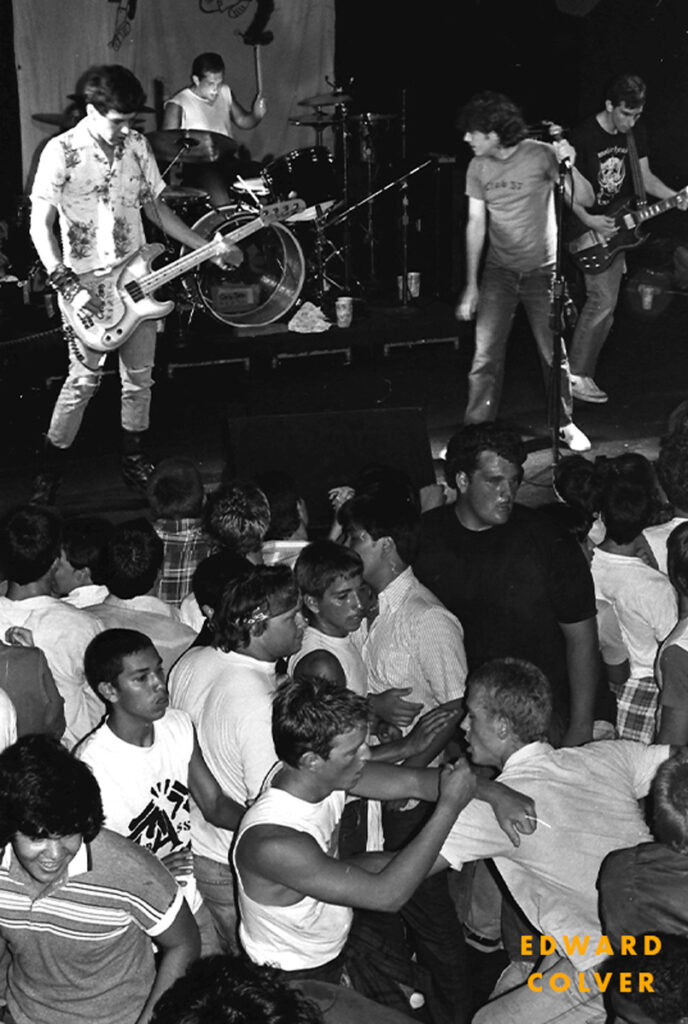

THE MAKING OF GROUP SEX

Anxious to start playing shows, the four would scrap together as many songs as they could—including some leftover cuts from previous bands. The resulting fourteen songs would make up Group Sex, recorded in June of 1980 at the recently-built Byrdcliffe Studios. The album’s name was taken from the track “Group Sex,” a song with lyrics contributed by Morris’ then-roommate Jeffrey Lee Pierce of the Gun Club.

MORRIS: We had a moment in my garage where we’re rehearsing and at a point where we’re taking a break to drink beer. We’ve got our first show coming up in about two weeks, and here we are with about seven songs, maybe eight songs. I said, “You guys have played in other bands. Did you write any riffs while you were in those bands?” All of a sudden, there’s riffs being tossed into the pot.

HETSON: Anything else we might have been working on with other bands, [we’d] just bring it in and roll with it. And that’s how some of those songs ended up morphing, or purloined, from other bands and ended up being Circle Jerk songs.

MORRIS: At one point, the Circle Jerks were very disliked by the punk rock community in the South Bay of Los Angeles, because Group Sex has some songs on there that we borrowed from some other bands. I had written lyrics while I was in Black Flag knowing that a lot of them were going to get cut down, shot down. I’d written the lyrics to “Wasted,” and so we ended up doing our version of “Wasted”. All of a sudden, we had all of these bands in the South Bay that anytime you saw them at a venue you could see the smoke coming out of their ears. You could see the laser beams being zapped out of their eyes.

HETSON: I think “Back Against the Wall” was the first song we ever wrote as a group, when we were just getting together. It was a group effort right away. It just came together so quickly. I wasn’t playing [guitar] that long at that point. I knew to kick up a notch speed-wise and with the down strokes. That’s what I focused on.

MORRIS: Greg had played in a band with Falling James from the Leaving Trains, they were called the Mongrels. Roger Rogerson had played in the Angry Samoans just long enough to say he played in the Angry Samoans. Lucky… I don’t know if Lucky ever played in any other bands. So whatever riffs Lucky threw in were riffs that were just coming to his head. Lucky was on a creative streak coming up with riffs, ideas, lyrical patterns, everything like that.

HETSON: We weren’t together that long before we decided we should go in and record a record. Lucky had a friend who just got out of recording engineering school and he knew a studio.

MORRIS: There was a shopping bag full of skunk weed traded to compensate for the studio time. We were using a voiceover studio on the Desilu lot down in Culver City, West L.A. Now when I say Desilu, that means Desi Arnaz, who was married to Lucille Ball. It was their film studio movie lot. It was not a big studio, probably the size of a three car garage. I remember going in there one day and being entertained by Jeff Bridges as he was sitting and playing the piano. We had a period of about two weeks, maybe three weeks, where Greg would come over to my house in Inglewood with his little pickup truck and we would sit around and wait for [the studio] to call us. They would call us at noon and they would say, “We’ve got a three hour break from four to seven. Can you be loading in at four?”

MORRIS: There was a shopping bag full of skunk weed traded to compensate for the studio time. We were using a voiceover studio on the Desilu lot down in Culver City, West L.A. Now when I say Desilu, that means Desi Arnaz, who was married to Lucille Ball. It was their film studio movie lot. It was not a big studio, probably the size of a three car garage. I remember going in there one day and being entertained by Jeff Bridges as he was sitting and playing the piano. We had a period of about two weeks, maybe three weeks, where Greg would come over to my house in Inglewood with his little pickup truck and we would sit around and wait for [the studio] to call us. They would call us at noon and they would say, “We’ve got a three hour break from four to seven. Can you be loading in at four?”

HETSON: We pretty much get the call, show up, set up as fast as we could and start recording. It was pretty organic. We all were playing together. We did a few takes, picked the best one and then did a few guitar overdubs. That was about it, really. Most of it was live.

MORRIS: The songs were kind of Frankenstein-ed. Here’s the arm, here’s the torso. What are we going to do about the head? Are we going to put eyes in the opening of the skull? Are we going to cover it with flesh?

HETSON: For “Group Sex,” Keith was reading off of an ad from some throw-away sex paper that had ads for swingers parties [with] “We’ll come to your house and give you a massage.” Ads for strip clubs, that kind of thing. We originally used the number for the A-Frame, a swinger’s club back in the day. We found out it was a pretty famous one, and we figured “Well, they might get pissed at us. That might come back to us.” So Lucky said, “Just put my phone number.” So it was actually Lucky’s phone number. He would get calls from all over the country. “Hey, who’s this?” “I like your record. Is this really the Circle Jerks?”

![]()

THE RECORD LABEL

Circle Jerks, alongside the Flyboys, were the first artists on the freshly-formed Frontier Records. Founded in 1980 by Lisa Fancher, a former employee of Bomp! Records, Group Sex hit shelves October 1, 1980 as a healthy seller that would allow the indie label to sign bands like T.S.O.L., Adolescents, and Suicidal Tendencies.

LISA FANCHER, FRONTIER RECORDS FOUNDER: I was a big fan of Black Flag with Keith. So hearing he had a band with Greg Hetson, it was like a supergroup. Like, “Oh my God, Redd Kross and Keith?” The first time I saw Circle Jerks… let’s call it at the Hong Kong Cafe. The whole set was like 15 minutes, and I was blown away. I never dreamed I would put them out—I didn’t have a record label then.

MORRIS: At the time it was great: We’re in party mode, things are moving incredibly fast, and all of a sudden we’re offered a record deal. We’d already recorded the album.

HETSON: Back in those days, there weren’t many labels. Everything was pretty much DIY. If there were any labels, it was just people from the scene. I don’t think we “shopped it” to anybody.

FANCHER: I was still living at my parents’ house. I had moved out, and then when I had the label I couldn’t afford to do both, so I was living with my parents again briefly. Basically, I called up Lucky out of the blue. He was like, “Who the hell are you?” and was not into it at all. Then he talked to a few people—Rodney [Bingenheimer], Greg Shaw, maybe Kim Fowley. They all gave me the thumbs up, so the no turned into a yes.

MORRIS: So we signed a deal with Lisa Fancher at Frontier Records. She had, before us, only put out a band called the Flyboys.

FANCHER: The Flyboys record took forever. Over a year from beginning to end to put that thing out. The record came out in March 1980, and then right after they said, “Uh, we broke up.” I was like, “You gotta be fucking kidding me.” So by June I was like, you know what? I’ll just try one more time. Circle Jerks changed things dramatically, getting a yes from them. They already hated Posh Boy [Records], thank God.

MORRIS: We made an attempt to record an album for Posh Boy. We only made it through one song. They had us in this studio out in North Hollywood… it was fucking hell. It was 90 degrees outdoors, 120 degrees in the studio. You would go from the heat wanting to boil your skin while you’re walking on the asphalt that leads into the studio, and once you opened the door into the studio, it was like the bedroom in hell.

FANCHER: The first year Group Sex was out, it was really hard to keep it in stock. I couldn’t make more until I sold everything and got paid. I had a fucking sweet white Pinto with green racing stripes on it that went about 53 miles at tops, and I’d load those suckers up. Sometimes stores would say, “Gimme two Flyboys and 150 Circle Jerks,” and I’d drive out and deliver them.

MORRIS: It allowed [Frontier Records] to actually become a full-blown record label—a little indie punk rock label. So she signs The Adolescents. She signs T.S.O.L., she signed Suicidal Tendencies. She’s got hooks into some really big Southern California punk rock bands.

HETSON: At the time, very few bands were going in and doing 14 songs in 16 minutes on an album. We were actually worried that people would think they were getting ripped off, so we lied about how long the songs were on the original label of the album. We added a few seconds to every song.

FANCHER: I think we made it like a minute, maybe two minutes longer. I was afraid people wouldn’t want to pay for it. Like, “This is it? I refuse to pay full price for this record. Fuck you!” But nobody ever said a word [about the length]. They were thrilled—and then there were plenty of other hardcore records out that were similarly super duper short.

![]()

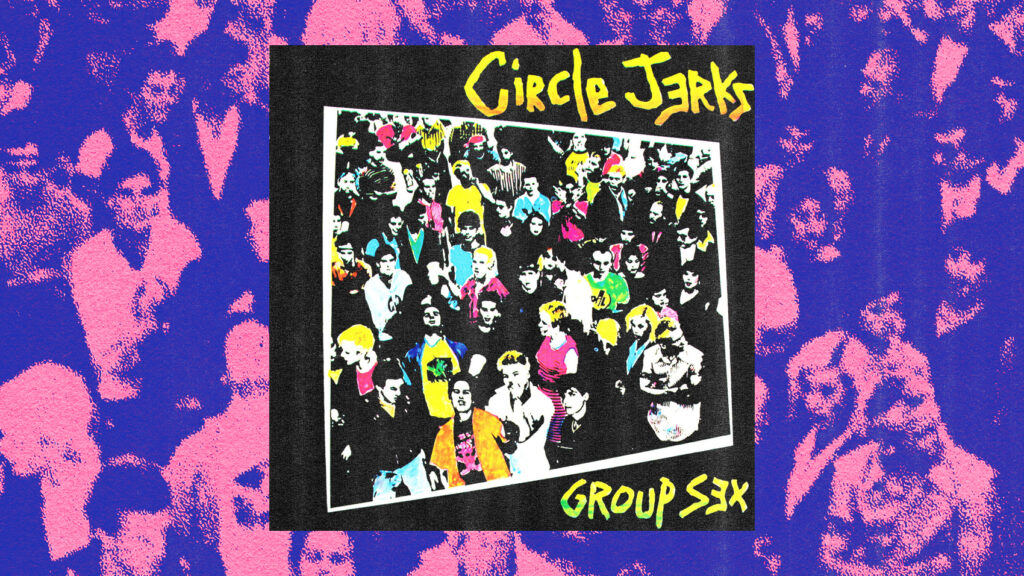

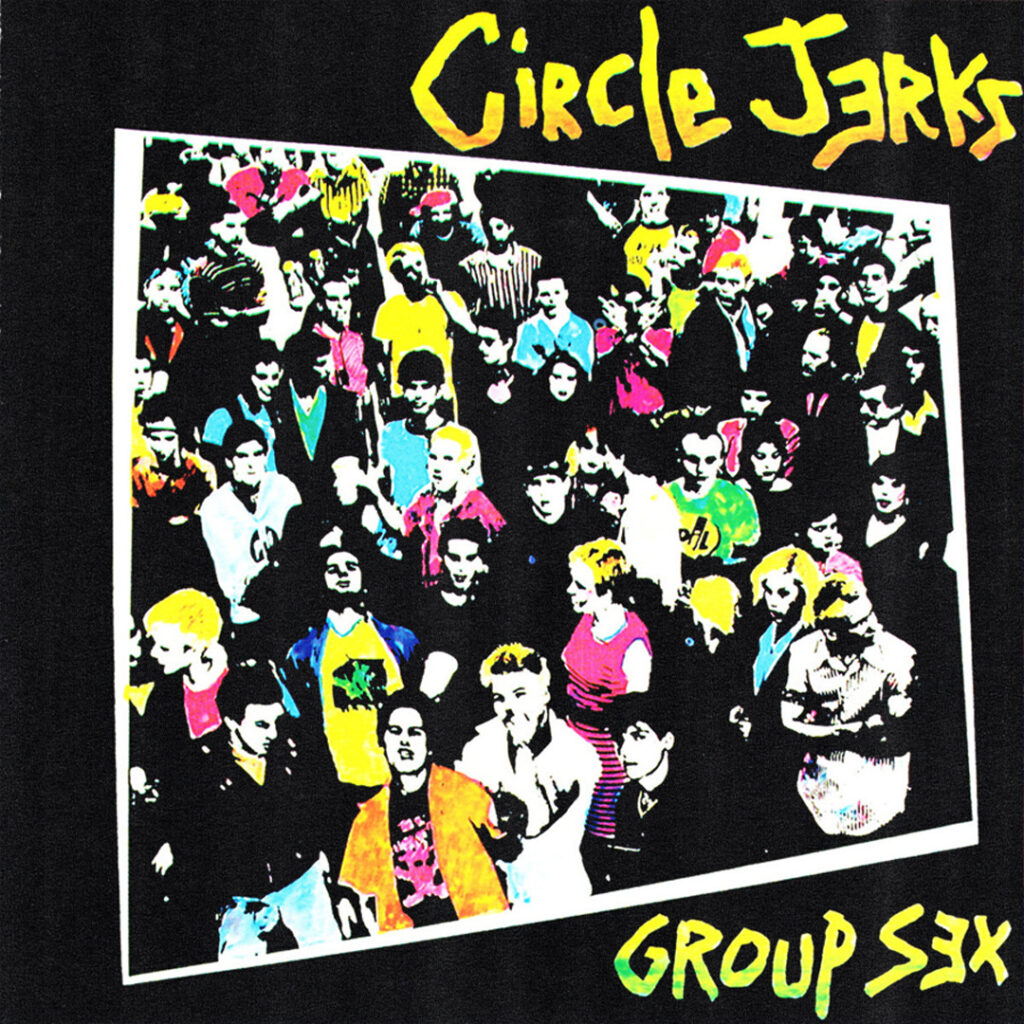

THE ALBUM COVER

The iconic photo on the cover of Group Sex was taken by Edward Colver—probably the most important photographer around capturing the peak of L.A.’s punk scene—at a concert held at the Marina del Rey Skatepark near Santa Monica.

EDWARD COLVER, PHOTOGRAPHER: I had shot some pictures of Circle Jerks at the Whiskey a Go Go and I showed them to Keith, who liked them enough that they wanted to use them on their record and asked me to do the cover.

MORRIS: Ed loved all of the bands. His story is that he was frequenting Madame Wong’s, which was more of a pop/rockabilly kind of place, and one night he saw all of the more colorful people that were hanging out to go into the Hong Kong Cafe. That’s when he decided, “Hey, I’m going to go and I’m going to check it out,” and that’s when he was sold on punk rock.

HETSON: There weren’t a lot of venues. People started renting out wherever they could to throw shows. And someone convinced the skate park that some skaters were going to get married and they were going to have some bands play.

COLVER: It was a fake wedding between Michelle “Gerber” Bell and Rob Henley, who drummed for the Germs. The Adolescents and Circle Jerks played that night, I think with the Stingers and Unit 3 with Venus. I shot the cover picture in the afternoon from a ladder next to the skate pool. It was a pretty scary prospect being up on a ladder with a bunch of punk kids skating around and drinking and stuff. Diane Zincavage at Frontier did the stat print and color treatment of it.

FANCHER: The colored bits [on the cover] I wasn’t that stoked about at first, and I didn’t know if the band would be either. It was kind of new wave. Diane wasn’t coming from a punk rock place at all—she worked at Bomp! where Greg Shaw’s whole thing was power pop and fluorescent colors. Anyway, they liked it, even the frames around the back cover pics. We fixed up their logo a little bit and the rest was history.

PENELOPE SPHEERIS, THE DECLINE OF WESTERN CIVILIZATION DIRECTOR: I remember everybody trying to find themselves on the album cover when it came out. You couldn’t really tell who was who.

FANCHER: If every single person in LA that said they were at that show was actually there… it would have been like, a hundred thousand people there.

![]()

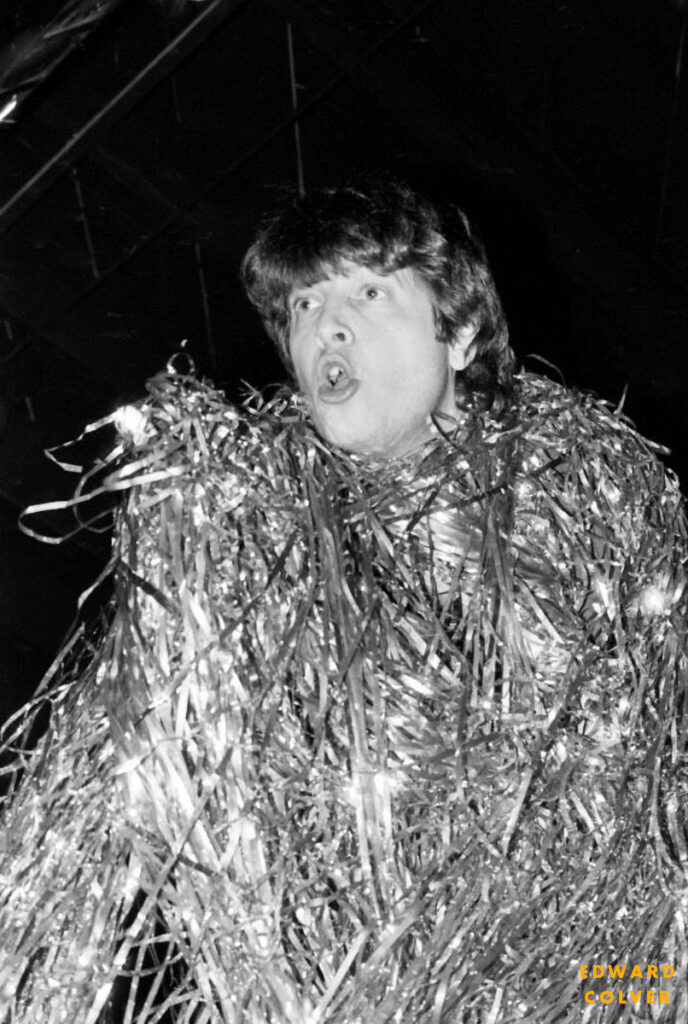

THE SILVER SCREEN TREATMENT

Just four months into being a band, director Penelope Spheeris filmed Circle Jerks—alongside Black Flag, X, and several other notable punk acts—in The Decline of Western Civilization, giving the Jerks a huge signal boost that helped grab national attention. The landmark documentary, added to the U.S. National Film Registry in 2016, premiered July 1, 1980 to the delight of the local scene—and to the absolute dismay of the LAPD.

SPHEERIS: The Decline was financed by a guy that my friend knew out in the Valley that wanted to make a porno movie. I told him I’d meet with him just for the hell of it. I said, “I’m not going to do no porno movie. That ain’t me. But I’ll do a punk rock movie.” He goes, “What’s that?” I took him to a Germs show and he goes, “This is freaky shit.” And so he put the money up for Decline.

HETSON: In L.A., The Decline of Western Civilization was a big deal. To me I always thought that the L.A. punk scene never got—well, except for locally maybe, and not usually in a positive way—the coverage and the press that the New York punk scene did.

SPHEERIS: I first saw Keith in Black Flag. I saw him at a show one night and said, “I really want you and Black Flag in The Decline of Western Civilization.” And he goes, “Well, you’re talking two different things now.” And I just thought man, what is Keith going to do? I didn’t imagine that he would form a band that would keep going and last so long, but he sure did. So when Circle Jerks started up, I of course asked Keith to be in the movie.

MORRIS: That was a huge monumental situation that happened for us. People were seeing the documentary and were getting a really great idea of what’s happening in Los Angeles. It was a business card for us: This is who we are, this is what we do, take it or leave it. Things started to happen for us.

SPHEERIS: At first, I could not get a venue to show The Decline of Western Civilization. The first excuse was, you know, “Nobody will come to the movie.” Then they had to close down Hollywood Boulevard because too many people came. And then after that happened, I couldn’t get a place to show it because they were afraid that a riot would happen and people would get hurt.

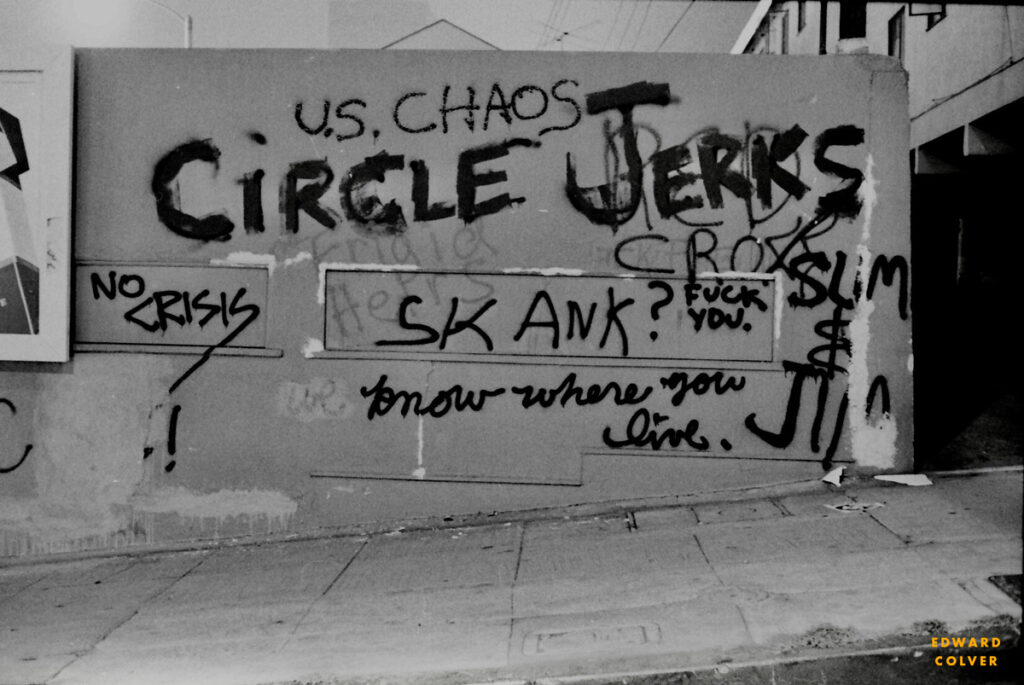

HETSON: A lot of people showed up for the premiere. The cops freaked out and called in the riot squad, even though nobody was doing anything.

FANCHER: The police had just absolutely decided they did not like punk rock and they did not want it happening in LA.

COLVER: There was some communist passing out Revolutionary Worker newspapers, and the punks started getting all rowdy with him, giving him shit and throwing the papers all around. There’s a photo where you can see Hollywood Boulevard looking east, and there’s a bunch of Revolutionary Worker papers that were blowing around the street that the punks had thrown around.

HETSON: A riot ensued. There’s a pretty famous Ed Colver photo of all the police and riot squad lined up on Hollywood Boulevard in front of the theater.

COLVER: I mistakenly thought the premiere was at the Brahmans. I went up there with a couple of my friends and they said, “Oh no, it’s not here. It’s down the street.” I looked east and I could see all these cop lights—I took off running down there to get the pictures. A friend of mine was on a nearby roof and he said he counted 71 bikes, seven patrol cars and two Paddy wagons.

HETSON: We were lucky. It really took us from a local band to a more national or international audience.

MORRIS: It didn’t just open doors for some of the bands. It kicked down doors for some of the bands, X and Black Flag. All of a sudden, there’s people in Chicago, there’s people in New York, there’s people in Washington, DC [that are] getting to see it rather than just hear it.

SPHEERIS: Keith was very instrumental in helping me put together that Fleetwood show where we shot the Jerks and Fear. Unless I’m not remembering right, I think Keith is the only person who was in The Decline from a band that ever thanked me.

![]()

A REUNION-WORTHY LEGACY

Celebrating the 40th anniversary of Group Sex, Keith Morris and Greg Hetson are now back together as Circle Jerks for the first time in 11 years. The two will be joined by longtime Circle Jerks bassist Zander Schloss and a yet-to-be-named drummer. The reunion tour’s warm reception from fans is just one sign of how well their debut has aged.

SPHEERIS: What I think about Group Sex now is different than what I thought about it then. Now in retrospect, you can see the profound difference it had from other albums that came out before that.

FANCHER: I don’t have a good story about the most memorable first time I heard it or anything, I was just like thrilled. Like I just thought it was the greatest thing in the world. I still do.

MORRIS: There were a lot of people that were excited about [Group Sex] when it came out. All of our local press was all extremely favorable. I believe they weren’t really finding too much to be upset about. It’s a party platter. You’re going to throw a party and you want to get some shit happening? You roll in the keg, toss our record on, and they’ll be toilet papering all of the trees. They will be smashing all the windows out. They’ll be creating a mess so that whoever throws the party understands that they’re going to need some of their friends to help clean up before the parents get home on Sunday night.

FANCHER: It’s just a masterpiece. You could just play it over and over and over and over.

SPHEERIS: They were so innovative and brave to do all the different things they did on that album at the time. It was kind of shocking. “You can’t sing songs that fast.” “Those songs can’t be that short.” “You can’t say those lyrics, you can’t name an album Group Sex.” You know? I mean, you can’t even name a band Circle Jerks. I remember thinking they just didn’t have any more songs, so therefore it’s a really, really short album. But if you stop and listen to the songs, it’s a lot of meaning packed into a short amount of time. It was way ahead of its time.

HETSON: A lot of us grew up with parents that could’ve been hippies or anti-war, very liberal that grew up during the Nixon era, that kind of thing. So that was still ingrained in us when we saw a new president come in that had ideas that we didn’t like about what conservation should be on foreign policy, about social issues, against welfare. We were like, “What the hell? This is happening again? Is it going to be worse? We want to do something about it. We can try to sing about it. And it wasn’t peace and love, it was, “Fuck the system. Let’s break shit and have a revolution.”

SPHEERIS: I think it was a most important time in music history back then. It changed everything, it really did. I don’t think people stop and think about the ramifications of change that happened because of that punk movement in the late 70s. It affected not only music of course, but social trends, fashion, political perception, and all kinds of different social attitudes. It really did make a paradigm shift in music. I haven’t seen anything like it since then, and it’s been 40 years.

MORRIS: When I walked away to work with OFF! with Dimitri [Coats], I had absolutely no thoughts whatsoever about ever playing with these guys again. And then we had a string of events that happened that made it [look] glowingly. It made me totally aware that, yeah, it is time to do this.

HETSON: It’s pretty exciting. We’re still trying to keep our chops up and practicing as much as we can. It’s a lot of fun. You forget how much fun it is to play these songs, and how it’s like, “Oh wow, that sounds actually pretty good.”

MORRIS: Part of our vibe now is that we get to show up and let everybody know that we’re not here to fuck around. Yeah, we’re older. We’re not going to be jumping around as much as we used to jump around. But we’re certainly not going to be lounging around… Maybe at one point during our set we’ll have one of our road crew roll out a sleeping bag, just in case I have to take a nap. I’m having fun. It’s a workout. I’m having a nonstop party festival with OFF!, and now here we are.