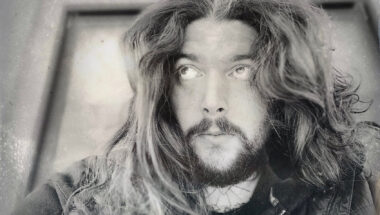

FEVER 333 vocalist Jason Aalon Butler says his approach in making music differs from that of many other artists because he’s an activist, first and foremost, before an artist.

“I want to make sure that whatever content we put out is ahead of the sonic appreciation. I know that that might sound kind of silly for a band, but I believe that music is the biggest tool I have to be active in participating in the things I think need to change. Music is my tool set. It’s the easiest way for me to affect change.”

Butler isn’t content just writing music about the changes he wants to see in the world, though. This summer, he joined other Black Lives Matters protestors and took to the streets of downtown Los Angeles, Hollywood, Inglewood, and South Central. After marching for 13 days, he recorded his observations and penned the band’s latest release, Wrong Generation. The eight-song EP is full of the rage and hope that Butler not only experienced during the 13 days he was protesting, but during the past 34 years of his life—including his experience being a Black teen in an alternative music scene. We spoke to Butler to coincide with Wrong Generation’s release last week to hear about these experiences, along with how he hopes to implement the band’s activism into livestreams.

RIOT FEST: What did you see while protesting that inspired you to write Wrong Generation?

JASON AALON BUTLER: I saw this ironic type of hope within struggle. While we were all coming together in solidarity based on tragedy, I saw people acting in ways that I hadn’t seen before, specifically for our generation. I saw in real time, in real life, right in front of my eyes, people putting in the work in order to aid in the progress we have claimed we want to see for so long.

I also saw a lot of what primarily people of color have lamented. Mechanisms of oppression, para-militarism—I saw that firsthand. So when people try to talk to me about exaggerating or embellishing stories—I was right there. I cannot be lied to. I saw these things happening against myself and other people like myself.

How did you transcribe that hope and struggle into music?

Wrong Generation is my story of the time I was out there. I don’t think that it’s better or worse than anyone else’s depiction, all I know is that it’s true. The sample of people chanting “no justice, no peace” is actually from two protests, one in Brooklyn and one in L.A. I recorded the sample at a protest at Beverly and Fairfax that I was at, but it’s played in tempo with a sample that my front of house engineer took from a protest in Brooklyn. It’s amazing — people chanting together from coast to coast.

You’ve said that FEVER 333 is “art as activism first,” and your upcoming livestream concerts are labeled as “demonstrations”—that carries a heavy connotation and responsibility. How do you live up to such bold assertions?

There’s so many ways for people and artists to be performative and pretend they care. I had this conversation with one of my friend’s in a hardcore band who thought I was co-opting this idea of revolution being trendy: If your first step into this world of protest, of this movement is to find a way to get a check, you are fake. You’re not real. You can’t walk into this and get paid, because revolution has never been pretty or profitable.

Everything we do is aligned with charity efforts. I have a foundation called Walking in My Shoes that is affixed to the band, so every time anytime there’s a profit I find a way to funnel that back to the community. If I’m going to go talk about the idea of change and affecting change, I have to give back to that. One of the things that can help the issues I discuss in my music is money. Today, in a Western world where capitalism and currency offer themselves as one of the largest pillars, I need to feed into that, whether I like it or now. The profits that we get from performance or merchandise or ticket sales will always go back to charity. Before we started this ramp up with the new single, we took everything down off of our Instagram and we put up three posts highlighting The Trevor Project, Color of Change, and When We All Vote. Those are the organizations we’ll be putting our proceeds towards.

For a listener who’s new to activism, what do you want them to take away from Wrong Generation?

Empathy. To say, “I might not align with this, I might not have this experience, I may not even know if this is true.” By turning on that song or putting on the headphones and understanding that if there’s a dose of authenticity in what is being said by the artist, it connects you [to the artist’s situation], even though what they’re saying is something that could possibly be antithetical to your own belief. That’s some wild psychology right there when you really think about it — it’s the power of music. You hear something authentic that captivates you and engages you in a way where you almost feel as though not only do you want to listen, but you have to listen. In those moments, I really hope that people can at least extend empathy.

I hope that people can look back and say, “I really didn’t know what he was talking about, and I might still not, but I believe that he meant what he said, I believe that he had that experience. I believe that he felt that way.” And when they believe me, maybe they can stand up for the average person on the street. Maybe they can extend empathy because they’ll think, ‘well, I listened to this one brother who said this on an album one time and it made me think that even though I don’t see it, or know it, or get it, doesn’t mean that it’s not real.”

Is Wrong Generation giving a voice to the “average POC on the street,” as you said?

I hope it is. I spent my whole life in this rock/alternative/hardcore/metal scene always feeling a little apprehensive to really let go and be Black in this scene. I know there’s someone who feels a sense of discomfort due to a lot of the problems that we see outside of self-proclaimed alternative music. A lot of those problems seep into the alternative scene in space that actually touts itself as progressive but, a lot of times, has a lot of the same problems that we’re yelling about on stage. They’re exhibited in the behavior of our peers.

I really hope that a young Black or Brown or BIPOC person out there—or a person who just feels outside of that white heteronormative sliver of hardcore or rock or alternative hip-hop music—and they realize, ‘I’m not the only person that feels like this. This dude feels this way, and he’s in a band that’s able to say and he gets to play on stages. Maybe I could do that, too.” You know, I needed that as a young person growing up, so it would be my privilege and an honor to offer any type of representation to anybody that feels that they fit under the banner that I’m trying to fly. I’m not championing anything, it’s not about me. It’s about me and a bunch of other people like me, and we need to hold that banner up together. So if you want to come under the banner and hold it with me, let’s go. Because it’s not about me, it’s about all of us.

The upcoming FEVER 333 livestreams have promised to deliver more than any other virtual show. What are you going to be doing to set your shows apart?

If other people are doing livestreams, I want to do it in a way so that the patrons get what they deserve instead of the same old shit. That being said, we have proprietary audio technology that allows us to have guests from around the world come up on the screen. I have guests from London, Philly, Virginia, and Australia coming in to sing parts with the band in real time. They’re actually playing with us, it’s not pre-recorded—it’s live. So if I slip up, if I fall on stage, you’re gonna hear it. The charm of a live show is that everything that happens in that moment can’t be edited, and that’s what I want to exhibit.

What will it feel like when you get to step onto a stage again at Riot Fest 2021?

Surreal. I found so much solace and the catalyzation of my forward thinking brain through music, and I was able to share that energetically at shows. It means so much to me to be able to facilitate my own show, just as much as it means for me to be at a show as a patron. So whether I step on stage or whether I’m looking up at a stage, I truly feel that sense of freedom—that we took for granted pre-COVID—is going to be amplified, but in ways we’ve never experienced before. When we have our first return to live performance, I don’t think we will have ever known a show the way we will then. I can almost guarantee that because in the artistic parameters that we exist within, we really lean into the idea of freedom and expression—we really believe that shit. We’re about to explode when we come back.

You can catch two FEVER 333 livestreams later this week—the first for West Coast and Mountain cities on October 29 at 8:00 p.m PDT, with the second streaming for Midwestern cities on October 30 at 9:00 p.m. CDT. Tickets are available here.