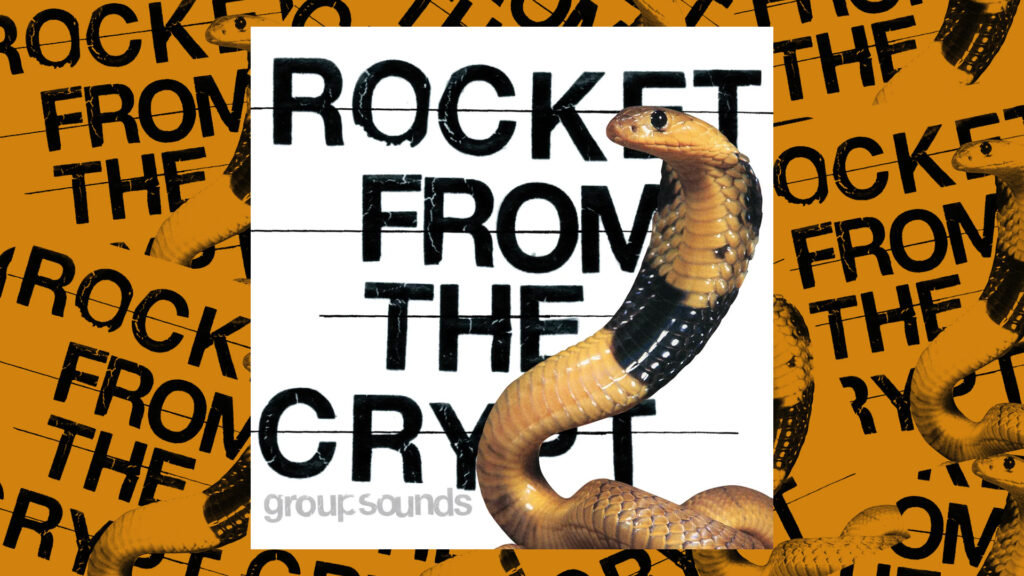

For nearly four decades, John Reis has been a dedicated missionary for the rock & roll cause. Though Reis’s name is a stamp of quality on any of his pursuits, a few of his (many, many) bands have drawn a particularly large and tenacious following: Hot Snakes, Drive Like Jehu, and of course Rocket From the Crypt, who will be performing their 2001 album Group Sounds in its entirety at Riot Fest this year.

We caught Reis on the blower just before he headed off on a short West Coast jaunt in support of his new album under the name Swami John Reis, Ride the Wild Night. He was generous enough to spend some time with us revisiting the heady days around Group Sounds‘ recording, discussing how punk hair care has changed since the early 1990s, and a lot more.

RIOT FEST: On the subject of products used on the road: accounting for inflation and everything, how does Rocket From the Crypt’s hair products budget differ from 1991 to now?

Well, I can only speak for myself on this matter, but the budget is probably more now! Back then, a can of Murray’s would last probably a solid month and wasn’t that expensive. Now, though, the medicine to restore the damage from those years far exceeds the cost of any kind of petroleum product you could find!

There was a lot of petroleum in the band’s old publicity photos.

Yeah, it’s all grease. We were a band full of pillow killers. We left a greasy trail of pillowcases in our wake.

That’s still one step above some of the punks I knew back in the ’90s, who would use wood glue.

Yeah, for liberty spikes! About 10 years prior to that, a lot of people would use Knox gelatin, which is like horse hooves. You’d put it in when it was in its liquid state, then once it dried it’d be hard as a rock. It works really well. I’d bet wood glue, which I believe is also made of hooves, is probably even stronger, since it’s designed to hold things in place.

Some things people would use would just backfire. I went to a show with a friend who used soap to put his hair in place, which worked really well until things got sweaty at the show. Then, it started falling down, and he was crying because there was soap in his eyes. He kept washing his face, but there was so much soap in his hair that it kept going right into his eyes!

Another guy used egg whites, which I guess worked, but it smelled exactly like you’d think.

You’re doing Group Sounds in full at Riot Fest this year?

That’s what we said we were gonna do! It’s not a thing we always do, but that’s our intention, yeah.

Have you had a chance to run through all of it with the band? Do you foresee any challenges with it?

No, and yes! There are a lot of songs on every record we’ve made that we never play live, or that maybe we played them a couple times and ditched ’em because they weren’t very fun to play. Group Sounds is one of my favorite records by the band, but it’s not without a couple songs that just didn’t fully click live.

There are always those songs that just don’t work when you try to bring ’em in front of people.

I also think that sometimes we recorded songs which we knew we probably wouldn’t play. We liked them enough to record them, and from there you just hope for the best. Recording a song is kind of like taking a snapshot and freezing it in time, or multiple shots since you’re taking a different picture of every instrument and performance. You never know how it’ll come out.

To this day, I enter every recording with ideas of what I do and don’t want, and a feeling of how I want it to come out. I want it to sound a certain way, but more importantly, I want it to feel a certain way, but at some point, you’re no longer trying to achieve something, you’re just dealing with what you have.

What was memorable about the process of making Group Sounds?

It was a really fun record to make. It was a comeback record for the band. We’d begged to get out of our major label obligations because we weren’t seeing eye to eye with them, and our custodians at the label weren’t working there anymore. One person in particular, she was an advocate for us and the reason we signed with the label, and she was no longer there.

It wasn’t fun. They didn’t do anything wrong, but we just didn’t have anyone there. So, we begged to get off of the label, they said no, and so we fought with them—not physically, that would’ve been fun!—until someone wrangled the situation and was able to get us separated.

We walked away without a drummer. Our drummer had moved to Los Angeles to pursue more consistent work with bands that were headed in the right direction, as opposed to Rocket From the Crypt, who were then descending.

We wrote a bunch of songs with the help of some friends, including Tony Brown (AKA Tony Di Prima) who I later played with in The Sultans, and Chris Prescott (from Tanner, No Knife, and now Pinback). They would come help us write songs and put drums to things. Then, we auditioned a bunch of people, which was crazy, but it was fun to see the kind of affection people had for the band that they would come from all over the country to audition. However, it also made us realize that we didn’t want to be responsible for someone’s happiness in that way. Too much commitment, too stressful. It didn’t seem organic.

When we started recording, we reached out to one of my favorite drummers and a friend, Jon Wurster (Superchunk, Bob Mould, The Best Show on WFMU, etc.). The whole band had always admired how Jon played in Superchunk. His style seemed to come from a singer-songwriter place, meaning that he listens to the song and does what he can to make it shine. He knows when to step on the gas, and he knows when to pump the brakes. So it was exciting to record with him.

Right around this time, though, Mario [Rubalcaba] became an option. We all knew him as this explosive drummer from this band Clikatat Ikatowi, who were the most exciting band in San Diego for the brief time they were together, an improvisational noise/hardcore band. We’d never seen anyone play drums like that.

We’d heard Mario had moved back to San Diego, so we tried him out. It was a great first practice, but I wasn’t completely floored. The second practice, though, oh my God, some of that stuff had never sounded better. As the chemistry evolved, it turned into something that gave us confidence that we could be not just as good as we were, but better. It also made us more ambitious, because Mario brought his scope of influences, which brought a lot of new sounds to the plate. My palette definitely expanded because of the music Mario was turning me onto. It was kind of a rebirth.

We took the title Group Sounds from a style of Japanese rock & roll, Japanese bands that were influenced by the British Invasion and stuff. I liked the double meaning: we were influenced by that stuff, but also we had reconvened as something bigger than its separate parts. It was a “Group Sound”.

Could you expand on the influences Mario brought to the table?

Well, we were both into garage stuff, and at that time [in the early 2000s] there was a renaissance of 1960s and 1970s stuff getting reissued, stuff that had been impossible to find. This was before you were able to have every song in the universe on your phone. You still needed a physical copy to hear it, but this really niche stuff was still more available than it ever had been.

So, we were listening to these reissues from all over the world, including some 1960s Western-inspired music from Asia, Eastern Europe, Central and South America. Then there was a ton of 1970s stuff like the Testors, who were contemporaries of the Ramones and the Dead Boys but didn’t get talked about because they only had one impossible-to-find seven-inch come out when they were around!

These kinds of things were happening all over, and it was really inspiring. I was still listening to our peers, but I was really excited about this archival stuff, garage and primitive punk stuff. I don’t think I ever purchased more records than I did in that period of the band.

That’s around the time that I got serious about record collecting, and it was a great time for that stuff getting reissued. I was particularly into the Cleveland proto-punk stuff, which—given the name of your band—I’m sure you’re familiar with.

Yeah, that label Smog Veil was really doing a lot of great stuff then! I love the Cleveland music scene: Pere Ubu, Dead Boys, and yes indeed, Rocket From the Tombs. That is where we got our name. I read about them in, I think, Black To Comm, and they were talking about this band of people who went on to be in several of my favorite bands, and the article ends with, “Yeah, you can’t hear them, there’s no recordings”.

So, we named the band Rocket From the Crypt, and then this bootleg 12″ of Rocket From the Tombs stuff came out in the early 1990s. We were like, “Oh, no big deal.” More legit reissues came out later, and then the band actually got back together! That wasn’t supposed to happen!

Seriously, I was really glad it happened, and I hope we played a tiny part in it just by irking them because they’d had the name first. Us basically stealing their name was very innocent, because I had a love of that stuff and wanted it to be an ode to this mythical unicorn band that didn’t exist in any tangible terms beyond the lore.

You just made a solo record. How’s the songwriting process different between that and a Rocket From the Crypt record?

Well, I haven’t made a Rocket From the Crypt record in a long time, aside from a couple singles a few years back. It’s been a very long time. There are things I do differently now just due to experience, regardless of which band it is. I tend to do a lot more at my house. We’ve got a good 8-track and a killer little board, and I have some great friends who are amazing musicians, who make every idea I have sound better than how it sounded in my head. In that way, it’s similar.

As far as the songwriting, my process hasn’t really changed, beyond the fact that it’s not Rocket. I’m listening to different stuff, or have different sounds in mind at the moment, but Rocket was about that, too.

The difference, I guess, would be that on my own, I don’t have to be accountable to anyone other than myself. I’m just doing my own thing, I won’t be frustrated by conflicting schedules or artistic differences. I won’t have to tell someone what to do or have an artistic discussion (though that’s a fun thing to have, for the most part). I just want it to be a certain way, and then move on.

The playing is a lot different, though, just because I’m surrounded by different people who play quite a bit differently. Rocket is a girthy rock & roll sound, and my own stuff is intentionally more approachable… weaker! You don’t have to navigate through a barrage, for better or worse. That onslaught, though, is a big part of the appeal of playing in a ferocious rock & roll band; this is just being ferocious with sounds that are a bit more naked. There’s piano and acoustic guitar on every song; it’s a different vibe, but to me it still feels more or less the same.

It’s texturally different, but you are a particular kind of singer and songwriter. It’s probably not going to be a free jazz record or a prog record, though maybe that would be cool…?

Yeah. There are a lot of kinds of music I like, that inspire me, but that don’t make it out in the music I do. Sometimes something has to sit with me a long time before it has an audible effect. The first Hot Snakes record was heavily influenced by the Wipers, Saints, Suicide, and none of that was new stuff to me. I didn’t just hear it one day and say “I wanna make a record like THIS!” Those were Rocket’s influences, too, but it didn’t come out as literally until it had been with me for like 10-15 years. As a guitar player, there were maneuvers that I could navigate that I hadn’t been able to before.

You’ve been fortunate to have been a number of bands that have maintained a solid following for a long time. Among those, what do you think makes Rocket From the Crypt special?

I think it’s our commitment to having fun. It’s probably the main priority. It’s a celebration of life! We put a lot of hyperbole around it, trying to justify our rock & roll existence. We didn’t really think we were rock & roll messiahs, but it was a culture that we felt responsible for spreading.

Rock & roll isn’t cock rock. Having fun is meaningful, celebrating our similarities instead of magnifying our differences…these are things we would say, but we actually believed it! We talked a lot of bullshit, but we believed the essential tenets of that stuff, and you have to believe that to commit the way we did. We felt that it was important to make friends and be custodians of this music. It was a sweaty crusade of hugs, handshakes, and high fives, and we knew that was as good as it was ever going to get.