On October 5 of this year, Portland, Oregon City Commissioner Chloe Eudaly stood in front of city hall and made an official proclamation that, within the city limits, the date would be known thereafter as Dead Moon Night. She delivered this proclamation to a throng of hundreds, all of them gathered to salute a group many would argue is the city’s greatest contribution to rock and roll since the Kingsmen stumbled through “Louie Louie.” All this, despite (or maybe partly because of) the fact that Dead Moon were never featured on the cover of glossy magazines, never had their t-shirts sold at Hot Topic or Spencer’s Gifts, and certainly never got within a mile of mainstream radio play.

One might expect it to feel surreal to stand in front of city hall as members of Poison Idea, Quasi, Smegma, and other local music luminaries took the stage to pay tribute to an ostensibly underground rock band, with that band’s core couple of Fred and Toody Cole looking on, perched nearby in thrones decorated with their band’s iconic logo. I mean, aren’t punks supposed to hate city hall, and vice versa? Yet, nothing could have felt more natural. At its best, Portland is a city built on punk’s most idealistic promises, and few bands exemplify the self-sufficiency, earnestness, and moss-caked raggedness of the area more than Dead Moon. As the crowd scattered on Dead Moon Night, the common feeling was a curious one: if there’s such a thing as punk civic pride, perhaps this was it.

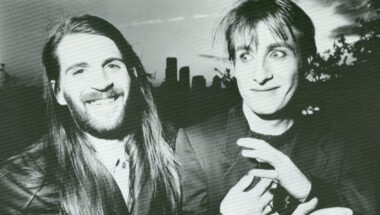

A little over a month later, the world has lost Dead Moon’s singer/guitarist Fred Cole to cancer, at age 69. While Cole is most revered, along with bassist wife Toody and the late drummer Andrew Loomis, for his work in Dead Moon, he was already an essential fixture in Portland’s music scene by the time that band formed in 1987. As owner of the music gear shop/community hub Captain Whizeagle’s, and as a member of punk band The Rats, the countrified Range Rats, and several other groups, Cole was a recognized lynchpin, a status which Dead Moon only solidified. Though he and Toody actually lived in nearby Clackamas, Portland had long adopted the Coles–and their music–as the city’s own. When Loomis left Dead Moon in 2006, a decade before he passed away himself, Fred and Toody bucked rock and roll retirement in favor of carrying on, with drummer Kelly Halliburton, in the band Piereced Arrows. In recent years, a gentler Fred and Toody would even make occasional acoustic appearances.

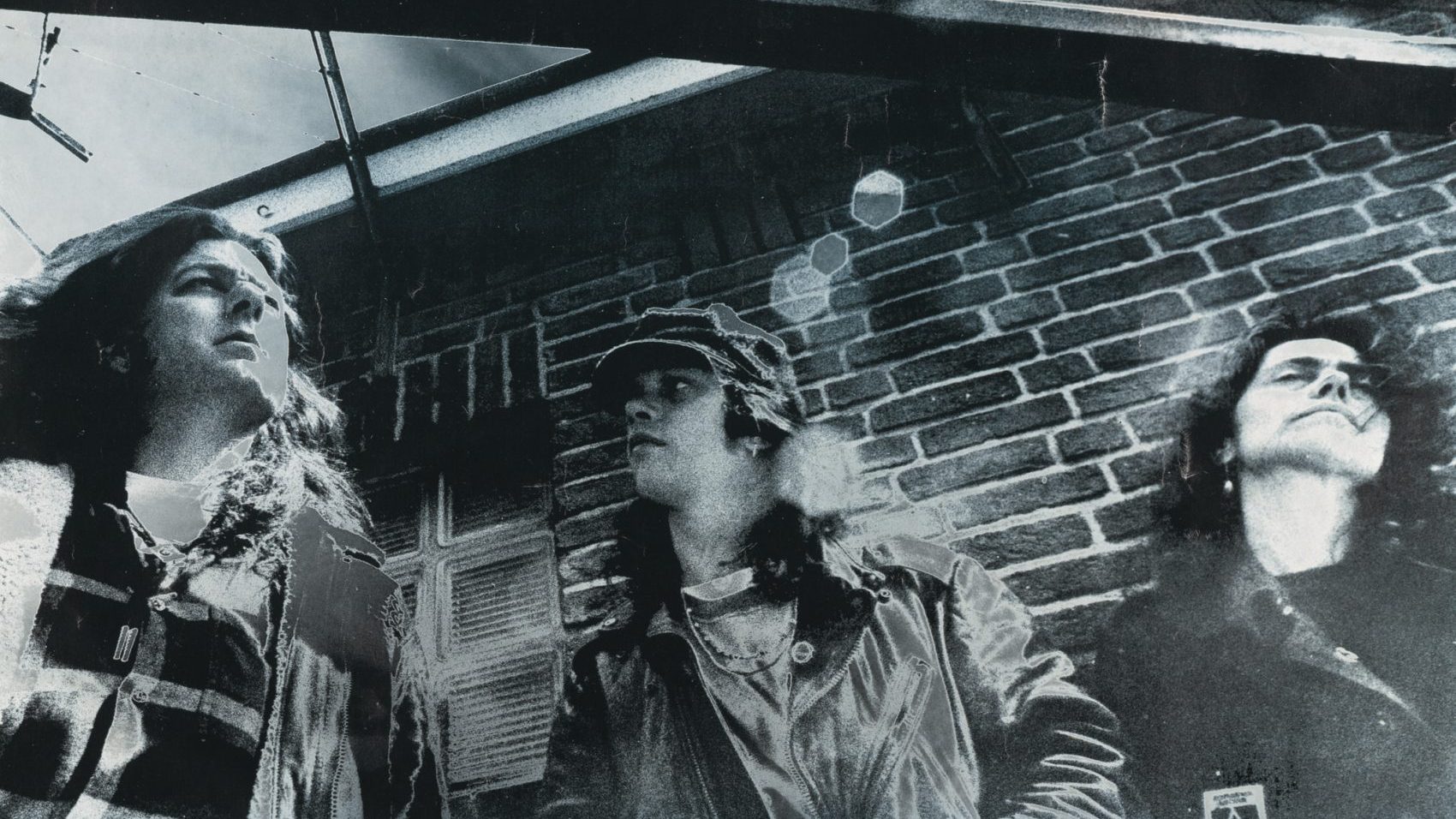

Though Dead Moon developed a large following worldwide, spending time in the Pacific Northwest affords the listener a key to understanding their appeal with greater depth. (Confession: it took this writer awhile to really absorb Dead Moon’s influence, but a few years of rainy days make their essential appeal a damn sight more graspable). Like their peers in the Wipers, Dead Moon are a widely acknowledged exemplar of what Pacific Northwest rock is about: self-sufficient, self-effacing, bedraggled, waterlogged, and largely unfettered by outside interlopers. Though Dead Moon benefitted somewhat from the grunge feeding frenzy that swept the region in the first half of the 1990s, there was no way that they were going to become the next Nirvana or Soundgarden: they were too weird, too old, and way too stubbornly DIY, making their more famous brethren look hopelessly compromised in comparison. Hell, their early records were mastered on the same antique mono lathe that was used to master “Louie Louie.” How would one have explained how important that is to Hit Parader or Sassy?

That’s not to say that those who did become major rock stars weren’t rooting for Dead Moon. In fact, Pearl Jam even took to covering their song “It’s OK” around the turn of the century, and have continued to work it into their setlists since. Though these kind of tributes never served to make Dead Moon huge, it certainly hasn’t hurt the band’s popular standing.

Still, Dead Moon carried their mark to the world at large in a decidedly more humble fashion than most, and this humility has ultimately paid off in underground reverence. They are the kind of band for which you get a tattoo, whose accompanying imagery is instantly recognizable by acolytes the world over. They’re the kind of band over which friendships are started. They were a band that spread the Portland gospel far and wide long before Stumptown coffee was stocked at Kroger stores nationwide, enterprising people in Japan started building “Portland-style” businesses in Tokyo, and Portlandia drew more of the dweebs they supposedly set out to mock into the city limits via their sloppy caricatures of the town. (In fact, a popular sticker frequently seen around Portland reads “Fred & Toody, NOT Fred & Carrie”). To paraphrase an anecdote from Quasi’s Sam Coomes which was shared from the stage at Dead Moon Night: when you’re a touring band, if you go anywhere in the world and tell an audience member you’re from Portland, they’ll probably say “oh yeah, Dead Moon.”

Cole couldn’t have expected any of this when he first ran out of gas in Portland in the mid 1960s, en route to Canada in hopes of dodging the draft along with the rest of his now-legendary rock group the Lollipop Shoppe (a name foisted upon them by their manager, and one completely unbefitting a group of miscreants who recorded tough, harrowing proto-punk like “You Must Be a Witch”). He probably didn’t expect to fall in love with–and eventually marry–a woman working at the club where the band started playing when they couldn’t afford to get out of town. It would have surely been unfathomable that he’d later teach that same woman to play the bass, and that they’d go on to become rock and roll legends despite the fact that their most famous band started when they were both creeping into middle age. It’s an unusual story, but it’s that hard-won, lifer element that makes it as inspiring as it is.

It’s often tempting to say, when someone iconoclastic and influential shuffles off this mortal coil, something like “they really broke the mold when they made [this person]”, or “they don’t make ’em like [this person] anymore”. To do so in this case would be as cloying as any other. Still, in his industriousness and dogged insistence on building his rock & roll world from the ground up, Fred Cole was indeed part of a very endangered species, and he will be dearly, sorely missed.