Pinning down the first song written in any particular musical style is an impossible task. Genres don’t emerge fully formed from the mind of a single creator, even if they can sometimes look that way in retrospect. The closer you look, the blurrier things get. For every landmark release like “That’s Alright (Mama)” in the history of music, there’s a “Rocket 88” lurking in the shadows, ready to complicate the story.

Putting your finger on the first punk song is even more complicated than other genres, because nobody’s ever been able to agree on what exactly makes a song punk (or anything, for that matter). Punk rock is the most malleable form of popular music because it’s just as much about how and why you play it, as much as how it sounds. Any music played to provoke an audience instead of simply entertaining them can arguably be called punk; which is how we end up with works like Stravinsky’s “The Rite of Spring” that predate electrified instruments, and can be credibly labeled as the first punk song.

That slipperiness is part of why punks have always loved fighting over what the first punk song is. (The other part being how much punks love fighting over pretty much anything with each other.) And it’s a good part of the reason why we’re devoting an entire week to airing out some of our writers’ thoroughly conflicting arguments for their nominees for the title. (The other part of that one is that we’re trolling for clicks on the sly.)

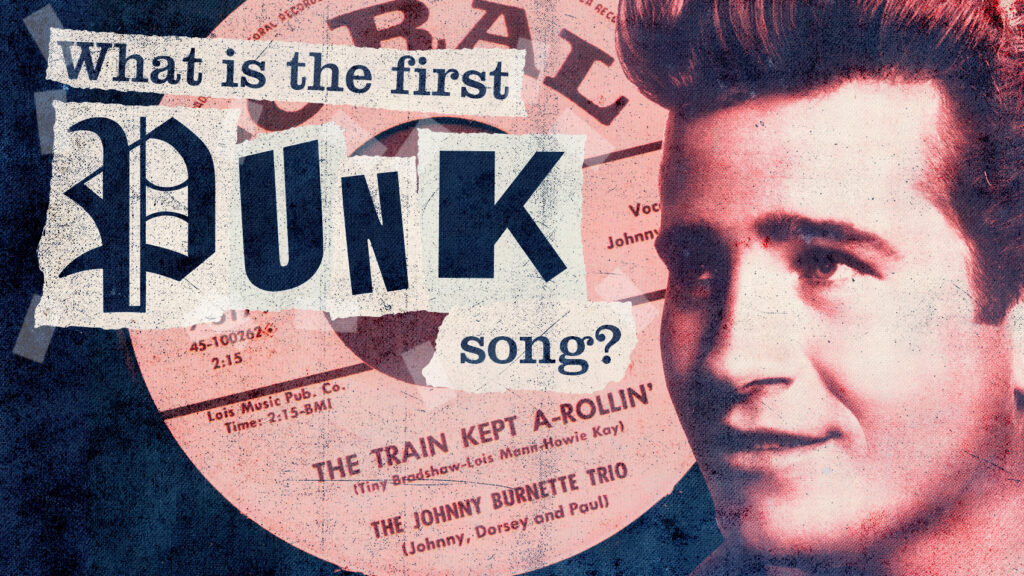

I think you could credibly argue that a plethora of candidates—from the Stooges to the Fugs to the Beatles—deserves the title, but my personal feeling (at least at the moment) is that the first punk song dates back to 1956, with “Train Kept A-Rollin’” by Johnny Burnette and the Rock ‘n’ Roll Trio. The song was originally written and recorded by Tiny Bradshaw as a jump blues number five years earlier—and incrementally modernized over time by the Yardbirds and Led Zeppelin, and brought into the rock ‘n’ roll mainstream by Aerosmith and the band’s classic 1974 sophomore album, Get Your Wings. But Burnette’s version paved the way, in all its ragged glory.

I realize that 1956 is early in the game to be calling something punk. Rock ‘n’ roll as we know it had only just recently cohered as a recognizable genre, which may be why Burnette and company must have thought that the Rock and Roll Trio was a cool, hip name for a band, instead of an almost fascinatingly generic one. Burnette’s former neighbor Elvis Presley was still a new star, and the style’s roots in (among other styles) jump blues and swing were still showing.

While rock’s edges may have still been raw, Burnette’s recording of the song was unhinged even by the standards of the young genre’s lunatic fringe. The group tackles Bradshaw’s composition like a street gang jumping an unsuspecting drunk walking home from the bar. They play it way too fast and way too loud, making the train in the chorus sound like it’s out of control, barely keeping this side of disaster as it careens down rails it’s barely hanging onto.

Rockabilly revivalists from the Cramps on down have tried to replicate the savagery that Burnette and the band got down on tape, and they’ve all failed. Burnette and the Rock ‘n’ Roll Trio summoned some serious chaos, tapping into something wild and primordial that very well may have sent some of the crankier puritans of the era (who could barely handle Pat Boone) to an early grave. Even now it seems absolutely crazed. But as much as the Sex Pistols would have loved to have gotten close to that level of sonic chaos, that’s not the reason why I think it qualifies as the first punk song.

I think it is punk as fuck due to the controlled chaos that seemed to be the whole point of the song. The blown-out guitar sound that drives the recording wasn’t just a byproduct of the low-fidelity recording technology of the time. Burnette’s version of “Train Kept A-Rollin’” is widely considered one of the first examples of an intentionally distorted guitar. Rock ‘n’ Roll Trio guitarist Paul Burlison had accidentally figured out that loosening one of the tubes in his amp would make it sound extra gnarly, so when it came time to record “Train Kept A-Rollin’” he did it again on purpose in order to get that noisy, nasty tone. (Unless it was legendary session guitarist Grady Martin playing on the recording, using a slightly different technique to get the tone, as has been theorized.)

A lot of bands from Burnette’s time and earlier sound raw and overblown from playing too rambunctiously, but this was one of the first times in recorded history that a musician made the decision to intentionally make their instrument sound worse: Anti-hi-fi, halfway broken, fingers raised to the very notion of pristinity. Burlison or Martin or Burnette or whoever had the idea to blow the guitar tone out had intuited the power of noise to take their music to a wild new place, to harness the power of anarchy to shred the minds of the people listening to them. More importantly, they knew that while a lot—or even most—of the listeners they reached would run from it, at least a few of them would get off on what it did to them. The better part of century later, we’re all still chasing the same high.