I cannot fathom why anyone would want to listen to sad music when they’re depressed. I’m generally just not the type to want to exacerbate my pain. I don’t think I’ve actually listened to Bright Eyes since the onset of my inherited clinical depression as a teenager. The closest I ever get to self-harm is when I read the In Memoriam page of the French bulldog adoption website I frequent. Though I’ve grown up loving Sylvia Plath, Girl, Interrupted, and Prozac Nation as much as the next chemically imbalanced girl, as an adult who no longer likes to revel in her own melodrama, the pop culture I turn to on my darkest days has evolved.

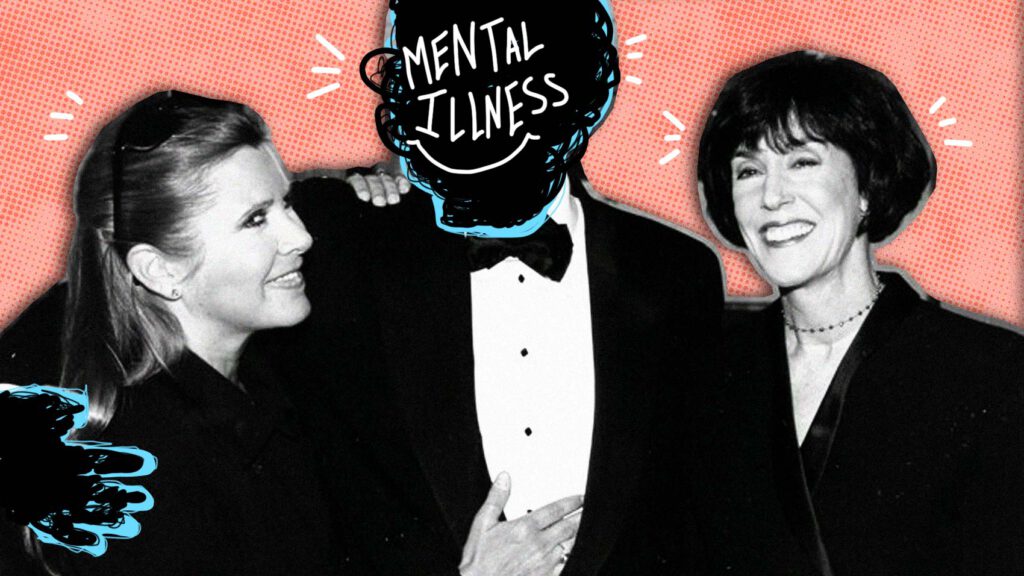

As I’ve sunk deeper into the cold depths of depression gotten older, I’ve discovered a deep connection to women who write candidly about struggling to live with an unruly mind, such as Nora Ephron and Carrie Fisher. Ephron lived by the motto “Everything is copy;” or inspirational material she could rightfully mine for her work.

Nora Ephron’s personal minefield included the harsh dissolution of her marriage and subsequent identification as a group therapy-devotee, later dramatized by her novel (and Mike Nichols’ film adaptation), Heartburn. She was the self-described “wallflower at the orgy”—the person observing the In Crowd from the fringes, accepting of the fact that she’d never fully fit in with the cooler, more carefree set.

Carrie Fisher was similar. She wrote at length about her battles with bipolar disorder and substance abuse. For much of her life, Fisher was deeply depressed in a way that the daughter of America’s original sweetheart, Debbie Reynolds, shouldn’t logically have been.

Fisher and Ephron were comfortable in their roles as misfits, but not so much so that they considered it a virtue. They discussed their illnesses like they were rude acquaintances, too dumb to understand the social grace of not making someone want to kill herself.

Unlike writers who wallow in their pain, their accounts gave me a roadmap through the process of getting my own head right. When I was seeing an incompetent therapist who would often have me spend our sessions “meditating”—I suspect because she just had nothing to say to me—Fisher’s wry self-awareness as she stared potential self-inflicted death in the face in Postcards From the Edge proved far more helpful. (Also cheaper, but c’est la vie).

I devoured Postcards From the Edge, Wishful Drinking (Fisher’s 2008 memoir), and Ephron’s essay collections like they were self-help books. There’s a great directness in their writing that made reading them feel like I was simultaneously getting advice from a fun, jaded friend and my own mother. They are matzo ball soup for my particular soul.

People don’t take women’s health seriously. We’re less likely to survive a heart attack than men because of our different, less publicized symptoms, and we’re less likely to be diagnosed with ADHD for the same reason. Unsurprisingly, the same goes for mental health issues. When I literally couldn’t function at my old office job because of the near daily panic attacks I was having, my doctor prescribed me a supposedly fast-acting anxiety medication called hydroxyzine. I quickly discovered that it wasn’t technically an anxiety med, but an antihistamine that was supposed to make me sleepy enough to forget the chemical imbalance in my brain? I only found this out when my mom told me that our family dog had the same prescription for when she gets stressed, and—here’s the kicker—she got a higher dosage! Maybe if I chewed on my hands and peed on the floor whenever it rained, I could have gotten some fucking Xanax.

Maybe that’s why, in recent years, women following in Fisher and Ephron’s footsteps have been leading the charge on normalizing mental illness through comedy. Comedy is an innate defense mechanism, probably most often used as defense against oneself; if no one else will take your pain seriously, you’ll eventually need to find a way to salve yourself. Ephron’s “everything is copy” theory states a similar idea: “When you slip on a banana peel, people laugh at you; but when you tell people you slipped on a banana peel, it’s your laugh. So you become the hero rather than the butt of the joke.”

Since 2015, Rachel Bloom’s Crazy Ex-Girlfriend has worked to upend the Hysterical Woman stereotype. Bloom’s character, Rebecca, has borderline personality disorder, but considering that the show is from her perspective, the “crazy ex-girlfriend” moniker has an underlying sense of ironic reclamation. The show deftly balances its careful exploration of Rebecca’s mental health and its genuinely funny broad comic sensibility.

https://youtu.be/1gSxKR0Cirs

Maria Bamford’s tragically short-lived Netflix series Lady Dynamite has a similar, but more absurdist handling of bipolar disorder. The show is a lightly fictionalized handling of a major breakdown Bamford had when her showbiz career blew up unexpectedly, and her attempts to navigate a comeback–including developing an autobiographical comedy series for a streaming network–that won’t trigger a relapse. Bloom and Bamford have different comic sensibilities than Ephron and Fisher wry quippiness, but they continue their legacies of refusing to let mental illness make them the butt of the cosmic joke.

Women handling their respective mental illnesses with brusk levity has been something of an American tradition since Dorothy Parker’s tenure as the country’s most shining wit. It’s the kind of misfit strength I find to be far more comforting than stewing in my own sadness. Spending my days intermittently taking depression naps and listening to the Smiths just sounds nightmarish (if not totally cliché). Though 100 MG of sertraline is certainly better medicine than laughter, figuring out how to deal with my depression without getting overwhelmed is a pretty good supplement.