In 1990, California rap crew Cypress Hill hit like a bomb. Their self-titled LP, released that August, was a revelation; a hard-hitting street-oriented message of “reality rap,” with a healthy dose of marijuana legalization sprinkled in. Anchored by the incredible beats of DJ Muggs that dipped into classic breaks by Lowell Fulson, Manzel, Grant Green, the Bar-Kays and more, the LP had a distinct East Coast sound that played off of the production of Marley Marl and DJ Premier. The streets on both coasts ate it up, and Cypress Hill was en route towards a hip-hop success story.

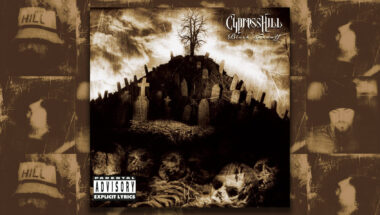

That wasn’t enough. Building off of the fire of the first record, Black Sunday was an unqualified smash hit due to the massive first single “Insane in the Brain.” Garnering heavy rotation on MTV, radio and otherwise, Cypress Hill became the biggest name in rap music, all while courting the controversial subject of marijuana reform. 2018 marks the 25th anniversary of Black Sunday, the record that made Cypress Hill a literal household name.

As the years went on, rapper B-Real and Cypress Hill expanded their territory by releasing several other hit LPs to massive audiences, all while sticking to a pro-cannabis narrative. Eventually that rebel spirit led to forming Prophets of Rage with three members of Rage Against the Machine and Public Enemy’s Chuck D; and, once laws turned in his favor, a dispensary of his own. We cornered B-Real before the group performed Black Sunday in full on opening night of Riot Fest 2018 to look back on the days when the term “marijuana reform laws” were dirty words, talk about the anniversary of these two crucial LP, and to see what’s good these days.

RIOT FEST: The self-titled felt like it hit like a bomb. Though there was relatively little fanfare at the outset, all of a sudden there were several singles and all of them were huge within the hip hop community, going further than just your average YO! MTV Raps rotation. What do you think was the key to the success of that record?

B-REAL: I think the key was Sony allowing us to do what we wanted to do in terms of the music, and then backing us up and being relentless, putting out seven videos –which at the time was pretty much impossible. When I look back at it, it was pretty impressive on what Sony did in terms of backing us up and making sure that we had great support and resources. None of those songs were hit songs on the radio. I mean, “Kill a Man” became a huge hit because of the movie Juice, but the songs weren’t meant to be hits or anything like that. And normally when they don’t see something marketable for the mainstream, they don’t give you that many videos. But I believe they believed in us and our vision. That was pivotal because of the lack of radio play that we got at the time. MTV was pumping us, as well as other video outlets that existed at that point, Video Music Box and stuff like that. So they put all the big guns and resources behind that first album.

If you look at the history of our band and the video releases following, they progressively got smaller. I think our success early on was attributed to, you know, pounding them out with those videos. If radio wasn’t going to play it, you were going to get these videos on MTV. So I think that was definitely important part of our beginning.

The promotional push behind Black Sunday was also similarly insane.

It was. We were on tour before we started recording Black Sunday and Sony called management and said, “Hey, we need to pull these guys off the road immediately and get them back in the studio,” because [the] self-titled LP was sort of floundering. It had been a year and a half since the LP had come out, and I think Sony realized that we started to have some traction on our first album later than usual, so they decided “We’ve got to get these guys back in the studio while we have this momentum.”

The LP was pretty much rushed. There were two songs that we used on that album that had previously been out: “Hand on the Glock” and “A to the K,” which was on the White Men Can’t Jump soundtrack. We were so under the gun to turn in the album at a certain date that we pulled those two songs and said, “Fuck it, we’re just going to put them on this album”. We felt that they were that good. So we took a chance to put those tracks on, and fortunately they fit with everything that we’re working on. We got that album done in about two and a half, three months time.

Though you were decidedly a West Coast crew, you always kind of had a Juice Crew/Slick Rick flavor. That said, what were some West Coast specific rappers that you looked up to outside of the obvious, like N.W.A/Ice Cube?

King Tee was someone that we looked up to. I think he’s one of the underrated west coast legends. We love and respect him to this day, and he remains a good friend of mine. DOC was another one – his unfortunate accident slowed his role in terms of what he was capable of doing. But realistically, our main influences in terms of what we were listening to, Sen Dog and myself, we were pretty much all about east coast hip hop and were heavily influenced by that. It was very much guys like Slick Rick, EPMD, Run DMC, Public Enemy and KRS One, those were some of our big influences there in terms of music and style of lyrics, cadence, delivery and all that stuff.

At the time, you guys were so outward about your advocacy for reforming marijuana laws, more so than virtually anyone in pop music. Did you encounter a lot of harassment from authorities?

I think in early times, there were a lot of obstacles thrown up because of the cannabis issue within the content of our music. A lot of opportunities went away from us because it was still sort of taboo. In terms of the authorities, yeah, occasionally they would show up to our shows to show a presence, but for the most part they let us do our thing. They got a kick out of it because they’re sitting there watching us smoke weed onstage and they think that it’s a joke. They must have figured that we didn’t have the audacity to do that. But we sure as fuck did.

I would say that the the one who tried to come at us [the most] was C. Delores Tucker. She was hell bent on outlawing hip-hop, going after us and Snoop Dogg and a number of other artists. But that fell on deaf ears because realistically, if anything, she lit the fire and made the flames go higher. What does the youth do when their parents or authority figures tell them not to do something?

Between Cypress Hill’s marijuana advocacy, Chuck D’s political discussion with Public Enemy, Rage Against the Machine, and multiple others, it seems like the 90s were more outward with politics than pop music is now, save for a very choice examples, like Kendrick Lamar. What do you think is the reason behind pop music’s whitewash?

I think people are tired of hearing about the rhetoric in politics. People are fed up with hearing the same bullshit. Nowadays, it’s a fucking circus. There are people so fed up with the back and forth and the lack of conversation that they are like, “I’ll never vote again.” That’s horrible to think about.

Today’s rappers, there’s only a handful of rappers that really have a message like Kendrick Lamar, J. Cole and guys like that. It’s great when you see guys with messages like that actually get some success. Less artists are taking chances on speaking their mind just for the sake of being successful. What’s going on today, the music is more celebratory and about nothing, so you can take your mind away from everything going on and that’s partially because it’s what radio perpetuates.

I’m not against any of this shit, because there’s always good music in all of it, and I won’t knock any artists for what they’ve created. But you know, the stuff that’s controversial and thought provoking is not marketable. Radio is not in it for the music, they’re in it for the money behind the ads attached to certain music playing in the certain time slot.

You joining Prophets of Rage always seemed to be a simple conclusion – it always felt like you personally flirted with a rock band from day one. You had the Judgement Night soundtrack, live band with Cypress Hill, and even did the dual single of “Rock Star” and “Rap Star.” Do you like performing in front of live instrumentation as opposed to a traditional DJ setup?

I’m adaptable, because the roots of where we come from is behind the turntables. I’ve been able to do both, but I was always a rock fan before I even knew what hip-hop was. It was ironic that I made my way into hip hop even though I was a metal fan first. It took a minute to get comfortable with live instrumentation, to be honest with you, because it’s easier to perform in the hip-hop aspect with turntables because the sound isn’t overwhelming. Live instrumentation is a little bit harder. There’s a little bit more energy because the sound is so powerful on stage that overwhelms you in a good way.

When we were using a band with Cypress, I feel like it prepared me to join a group like Prophets of Rage. I think that if that happened before I was ready, I probably would’ve botched it – I wouldn’t have been ready vocally to perform with these guys.

When I got the call for it, I was frankly surprised that it was happening. The possibilities of it were enormous to me. I heard through an insider that Tom Morello was going to call me but I was a little skeptical. Then Brad Wilk texted me and asked if Morello had hit me up yet, and I knew in that moment it was very real. When the band formed we all felt like it’d sound good to put our names together, but we’d have to actually see if we’d work together, and have the right chemistry from the stage and into the studio. Fortunately we found that chemistry.

I consider all those guys – Tom, Tim, and Brad – one of the best rhythm sections in the

history of music. And then to have Chuck D up there, the other rapper! Here I am with one of my idols, and then three other guys who I respect beyond words in a band together.

Let’s talk about your dispensary. It kind of feels like a forgone conclusion that this would actually happen. When did this whole thing start to come about?

Originally I was supposed to open up a shop in Santa Ana maybe three, four years ago. It had been a goal for a number of years. That didn’t work out in Santa Ana due to differences with partner at the time; we didn’t agree on some things and it just didn’t work out. So I decided not to open up in Santa Ana, and focused on growing out my Dr. Greenthumb brand.

It wasn’t until sometime last year [that] I was introduced to the guys who would become my partners in this particular dispensary. They were fans of Cypress Hill for years and were fans of my brand, and wanted to see if it was a possibility of a partnership in opening up here in Sylmar. When I discussed the partnership with them, we were on the same page about a lot of things in terms of where we could take this and how it should be. I realized that these were actually the right partners for this particular venture, we pulled the trigger on it, and it happened relatively fast.

We talked about it late last year and everything came together rather quickly because these particular guys had done their due diligence – licensing and permits and all that stuff – and had it ready. It’s just a matter of getting the right products on our shelves, and that can be easy, because we’ve been influencers in cannabis culture for such a long time.

I assume if there’s a ton of legal hoops that you have to jump through to do something like this…

Yeah. That’s the nature of this particular game, they don’t make it easy and they don’t make it inexpensive. It’s an investment to be certain. You have to be willing to stick it out and ride it out but if you got a brand and you’ve created it and you’ve done the right things, people will come in and fortunately that was the case for us.

One last quick question. As purveyors of the bucket hat in the 90s, who wore it better: Ian Brown of Stone Roses, or Parrish Smith of EPMD?

Parrish Smith all day. We were influenced from them with our bucket hats. We did something a little different, but that was all from our love for EPMD.