Roger Joseph Manning Jr. has worn many different hats across his decorated career in music. The eclectic songwriter/arranger/studio musician/keyboardist/etc. has not only been a founding member of several bands – including Jellyfish, Imperial Drag, and TV Eyes – but he continues to be sought after as a session coordinator, orchestrator, arranger, and mixer, working alongside producer Steve Aho in the studio. As a session musician, Manning has sprinkled his magic dust over the works of such Riot friends as Blink-182, Morrissey, and most topically, Beck, with whom he’s toured for several years.

For today’s Autodiscography, we communicated telepathically with Manning (working around his performance with Beck at this year’s Riot Fest) to cherry-pick his way through the vast and varied menu of the aforementioned bands, plus the synthgasm that is The Moog Cookbook, his own inspired solo work, and, of course, a fake movie soundtrack. Manning also reveals how those Daft Punk guys may have gotten the idea for their shiny helmets (SPOILER ALERT: Moog Cookbook).

JELLYFISH

“The King is Half-Undressed” – Bellybutton (1990)

“New Mistake” – Spilt Milk (1993)

RIOT FEST: Out of all the power-pop gems to pick from, why did you pick “The King is Half-Undressed” from Jellyfish’s first album Bellybutton?

ROGER JOSEPH MANNING JR.: That pretty much defined the sound of the band, at least to the public. This was our first single, our first MTV video. And, you know, it rocks out. But it has a lot of light, soft, very vocal harmony-driven sections. It’s like a snapshot of what we were about and trying to say to the public.

You’ve certainly been in a lot of bands. With that, of course, a lot of bands often break up due to bad chemistry or something that’s just not right. How discouraging can that get?

It’s totally discouraging, because it’s like a marriage – you invest everything. Music is the business of emotions, so you’re always wearing your heart on your sleeve, and always bearing your soul, putting yourself out for judgment. It can be very draining.

There are very few people who can compartmentalize it, and not have it affect them. It was challenging to keep the relationships going after six years. [Jellyfish] decided to break up for personal reasons. Well, mostly personal reasons.

I’ve had all kinds of projects that were very short-lived – except my solo work, obviously – and it’s always discouraging to realize, ‘Okay, this is falling apart, I don’t know how we’re gonna save it.’ I’m really proud of the music we’ve done… but it’s part of the game.

[Jellyfish was] really my first big venture out. I didn’t really have any history with anybody, nor my bandmates; We were just going for it. If you look at it just in the terms of what we put out there – and how it was received – it was a pretty good first run. Then, by the second album, we’re starting to get more momentum, as is typical. Certainly we were getting more attention in England and Europe… and it was basically the old ‘band members getting along’ kind of thing.

There are successful bands out there right now that don’t get along at all. They take separate limos to their gigs, fly in separate airplanes, and get together nowadays because it’s a money machine. They play one concert and get half a million dollars… It’s the nature of the beast.

I guess it takes a special kind of person to not be able to see the other band members until they go out onstage. That seems so disingenuous.

It becomes a business machine. I always joke if the members of Jellyfish had known about band therapy and therapists… Aerosmith almost broke up a bunch of times, but then they went to band therapy and they healed their relationship. It’s like a marriage, or a couple on the verge of divorce or something. I think maybe we could have salvaged some of the relationship.

We were very young, we were all in our mid twenties. We weren’t doing well in relationships with our parents or girlfriends or anything else, let alone each other. So it’s a skill set they don’t teach you in music school. They should.

When you’re that young, there’s so much to learn, and that’s when it seems like the most exciting music comes out.

It’s right in that time in a person’s life, particularly when they really want to be noticed and heard, [to] offer up what they’re sharing with the world. They’re really kind of going for broke. It’s a good period for an artist, because they really don’t care about trends and what’s trendy or selling or fashionable.

If you’ve got somebody starting out, and they’re already calculating what’s gonna make them the most money and have the most hit potential – whether or not they have their heart in it or not – I don’t really enjoy working those people. But at that time in your life, you’re usually going for anything, just to make some noise. You want to get people’s attention, and you wanna let your freak flag fly. ‘This is my version of what the world looks like. Check it out!’

That’s why a band like U2, or the [Red Hot] Chili Peppers… when they first came out, they were frickin’ weird. But then they found an audience. [An] audience came to them, and now those bands have had like 20 to 30 year careers.

Were there other songs from Jellyfish you wanted to add, something from Spilt Milk?

I would pick the song “New Mistake.” That was our second single, our second video. I’m really proud of it. I think it’s a good example of the spirit of this record… a representation that we’re still a rock band at the core. That song’s more poppy, actually. I mean, certainly in an early-‘98 sense.

Were you already arranging songs while you were in Jellyfish?

Well no, we were both playing; my partner [Andy Sturmer] and I had a lot of good arrangement ideas, but I was the one who had more music school training, whereas he was a really brilliant lyricist. A good song will sound good if you just strum it on the guitar and sing, but you can really have fun taking it someplace and presenting an attitude with the arranging. They’re all like mini jigsaw puzzles; and I was really having a lot of fun – and still do – figuring out those jigsaw puzzles of arranging.

Seems like being in Jellyfish was a trip.

Yeah, that was one of our goals, that we could afford to be very serious, well thought out, well constructed – you know, an artful poppy thing – but not so serious that we were never smiling, joking around, nor having any fun with the theatrical side of a live show. Some people were like, ‘How can we take you guys as serious songwriters if your clothing is so flashy and dressy, and your shows are so full of lights and spectacle and theatre and humor?’ We loved all those things. It was very natural for us to give all those things back to an audience.

Your music draws a lot from past eras, like psychedelic and classic rock. It seems like you should have been born in another part of the musical timeline.

I mean, maybe. You know, we were lucky to get signed at all. Our first album came out just as heavy metal was kind of ending on MTV. Bands like Guns ‘N Roses and… God, there were so many. And we had absolutely nothing to do with that world. About two and a half years later, after we’d toured a bunch and worked on a new record, the second album came out. Heavy metal was over, but grunge had started. And although we liked grunge, I mean, we had nothing to do with it. We didn’t write that style, so we were an anomaly in the record business for the duration of our career.

The whole grunge machine was going pretty strong at the time.

What was exciting was that there were plenty of people out there who were like, ‘Yes, this is awesome,’ because it was something different. It’s still catchy, you can still sing along, and you can still rock out to it and whatever, but it was different than what the typical thing would have been: punk and radio and MTV.

Our record company was excited about that. They had to work a little harder to get in with the other groups. However, there are fans out there that are still discovering those old records, and they weren’t even born when they came out. And it’s the same way they were when they discovered the Beatles and Big Star, or the Beach Boys, or Cheap Trick, or Queen, or Led Zeppelin, or any of those classic bands. That’s we tried to not make the songs we wrote [in-trend]. We just wanted to write timeless, classic, sing-along pop, and we feel we did that.

Obviously, we wished it was bigger at the time, but we can’t really complain about what happened… and we stood the test of time for sure.

How much did it help Jellyfish to have videos on MTV?

We got lucky out of the gate. The programmers at MTV really took a quick liking our very first video. I think they saw the potential in it, and they immediately added us to a pretty heavy rotation in the Buzz Bin. It got special treatment, which led to more radio airplay, which led to a larger audience. We were very fortunate that way, and I think we ended up having two more videos from that album that got thrown into the Buzz Bin rotation.

IMPERIAL DRAG

“Zodiac Sign” – Imperial Drag (1996)

“Illuminate” – Imperial Drag (1996)

Imperial Drag has had a rather large cult following. Would you put “Boy or a Girl’ on the playlist, or a different one?

I would pick a different one. Let’s see. I would probably put… can I put two songs?

You’re an adult, you can do whatever you want.

The first song will be the “Zodiac Sign.” I feel it’s one song that really shares the attitude of the group. This group was also very hook-and-pop-driven, but it rocked out more than Jellyfish because it’s got a different lead singer. It’s got a different sound, but there are still clever moments we enjoyed. It’s modern in a sense, but also has a lot of an early-‘60s and ‘70s groovy aspect to it. There’s almost a sensuality to it that we really enjoyed messing with.

Then the other song I’d put on would be “Illuminate,” which is very much in the opposite direction. It’s really beautiful, ethereal, and ambient – but not a rock ballad – and it really transports the listener. It’s very flowing-in-space, but in our way, as opposed to a Pink Floyd kind of way.

There are a ton of tracks on Imperial Drag’s 2005 compilation Demos: 17 tracks on one disc, 19 on another, five on another. Why did you feel it was important to put out such a large volume of music?

Jellyfish broke up after two records, but there seemed to be enough interest in more music that we were approached by the record company that did the first two records. He said, ‘What else have you guys got?’ and we said, ‘Well, we have a ton of stuff actually because we demoed up a bunch of songs,’ not knowing which ones we were gonna be confident enough in to make the record. We spent so much time on the demos because we wanted to impress the record company.

Are you surprised at the group’s longevity in terms of its popularity now?

Yeah, definitely. I recently got a couple of emails – I’m not even sure how they got my email, maybe off Facebook or something – but, these two girls from Argentina who were both like 17, 18 years old. I was like, ‘How did you guys even find this?’

I’m so blown away that with all the hip-hop in the world – or this modern pop, or just whatever modern music is now – they were like, ‘How’d you guys come up with these songs? We can’t believe a band like this existed.’ Obviously, they’re connecting with it. It’s super flattering and it reminds me of how timeless music can be; how it really speaks to people.

You know, regardless of where they grew up, their background, what language they speak… Music transcends all that, and it makes me want to not be as old as I am, and figure out a way to go back in time to keep making music for all these people. I’m still making music, obviously, but I still got a lot of songs I want to do, and they take time.

TV EYES

“Fascinating” – TV Eyes (2006)

“Stop Me” – Softcore EP (2008)“She Gets Around” – TV Eyes (2014 Reissue)

I’m so bummed I missed TV Eyes when it first came around.

I would put the song “Fascinating,” and, let’s see, that’s probably good. Another song you could put, is from an EP with TV Eyes that only came out in Japan. It had some remixes, some demos, and some songs that just didn’t make it on the first record. There was a song called “Stop Me.” I believe Omnivore Recordings did a special TV Eyes release.

They came back with a 2014 reissue.

They just put the remixes on there, and a song called “She Gets Around.” If [you] want to hear the song “Stop Me,” I think [you’re] gonna have to go on YouTube, which is fine. That’s still a very TV Eyes song, but it’s more guitar-driven, more kind of late ‘70s punk, punk-pop, than it is synth-based.

What made your music evolve in that direction at that time?

For TV Eyes? Me and Jason and Brian had been playing with a French band called Air. We’d been recording and touring with them, and we just got to talking about how it’d be really great to put some sort of side project together of what was inspiring us at the time, [which were things] from our childhood, from the late-‘70s to early-‘80s, a lot of British funk and synth pop. Gary Numan (who sat in on “Cars” with Beck during Manning’s solo section of the group’s set at Riot Fest 2018), Buzzcocks, Killing Joke, Siouxsie and the Banshees, New Order, Visage… there’s so many great groups. What would it be like if we added our own ideas in that kind of framework, that genre… TV Eyes was born out of that.

It was fun to collaborate with those guys again. They’re my friends, and we got along as people. Jake and I had been in Jellyfish already. We wanted to do something that was not Jellyfish at all, something very different, and try our hand at that. So there was some definite intentionality behind it with some specific goals and intentions. That’s how it came out.

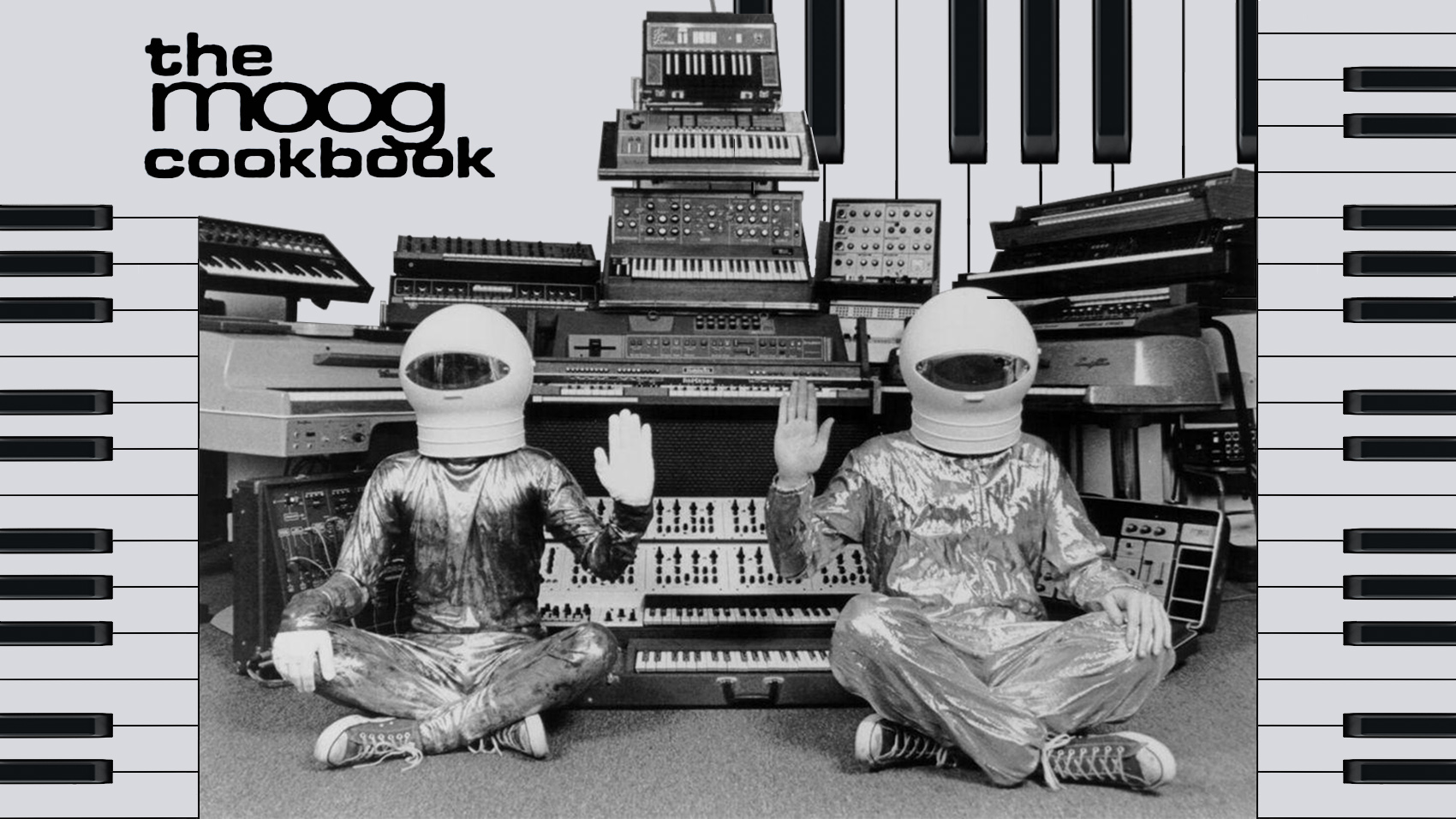

THE MOOG COOKBOOK

“Buddy Holly” – The Moog Cookbook (1996)

“Hotel California” – Plays The Classic Rock Hits (1997)

Next would be The Moog Cookbook, which is awesome.

I’m glad you discovered it.

Were you always interested in the Moog synthesizer, even when you were doing your other projects earlier on?

Yes, definitely. In the 70s, as a kid, I’d studied piano. Synthesizers were born, and they were becoming more commonplace on albums, but they were still very young. It was a new sound, and so I was very fascinated. But no one could afford a synthesizer; they were so much money. In the 80s and early 90s when Jellyfish and my other band started developing, a lot of those 70s synthesizer sounds were very out of fashion. So people who owned them weren’t interested in having them anymore, so they started selling them. And they started selling them very cheap because they didn’t think anybody wanted ‘em, and most people didn’t want them.

I met Brian Kehew because he was selling a keyboard in a trade paper here in LA, The Recycler… before eBay even existed. We started going hunting together and going to old music stores and looking in the paper for people who were selling. After about a year of this, we’d amassed a pretty big collection of old toys. But again, we were in the height of grunge music, so nobody wanted us to play these sounds on their records; nobody was interested, and nobody cared. Brian and I were like, ‘Well, let’s make our own record of our own use of these instruments.’

When the synthesizer first came out in the ‘60s, the Moog company had made this one model that was so expensive that only college institutions and giant rock stars could afford them, and movie soundtrack people who wanted to do weird sounds for their movies.

There was a trend of covering popular songs of the day – like Beatles songs, Beach Boys songs, and Rolling Stones songs – with synthesizers, and they weren’t supposed to be funny. It was supposed to be clever and interesting, and the creators thought that they would be easy-listening background music, ambient music. I don’t even know how well those records sold or not, but we collected those albums. We loved them. We thought they were just so entertaining, fascinating and interesting.

So we said, ‘Let’s do our own version of those cover records, those synthesizer records from the 60s. All electronics, all synthesizers, all drum machines, but where they covered 60s songs, we’re gonna cover modern rock songs, college rock songs, whatever was trending in the 90s.’ You see why we covered the songs we did – Tom Petty, Lenny Kravitz, Pearl Jam, Offspring, Soundgarden, a lot of early 90s groups. That’s where that came from.

It’s not really meant to be as a parody, right? It’s more of a tribute. Or, how do you see it?

You’re absolutely right. It’s a tribute to those records from the ‘60s, the synthesizer, in such a clever and very artistic way. Those records weren’t trying to be funny. They were trying to be very musical. There is comedy because we were trying to shape like a heavy rock song like a heavy Soundgarden song or a heavy Pearl Jam song. There were keyboards to make it lighter, but we’re not really poking fun at it, but presenting it in a different light; which, again, is the power of arranging. You can do that if you spend time working in arrangement details. Very often it would make us laugh, and we can make certain sounds with the synthesizer, or other comedic sounds that are silly and often evoke a lighthearted response from the listener.

In fact, people tell us that whenever their children would go crazy in the house, they’d put on the Moog Cookbook records, and it would calm them down [laughs]. I love that story. Their kids would start dancing like crazy to the sound of the Moog Cookbook records. Those records were both an homage to a bygone era of brilliant synthesis work, as well as having fun poking fun at those heavy, rock genres.

Oh, damn. I bet if you guys put on some shows or went on tour, it would fill up fast.

You know, we’ve talked about it, and we’d love to do it. But with every project, I don’t have to tell you, you’re always kind of weighing, ‘Well shit, for all the time and effort and hard work I’m gonna put in, there’s gotta be some kind of money return to pay my bills.’ So I’m not saying it won’t happen, but that’s why it hasn’t happened yet. Part of the wacky performances are us performing it that way. We can’t get a computer to play it that way. The computer would make it too stiff and robotic, which we weren’t interested in.

Is it true that Daft Punk they got the inspiration for their helmets from The Moog Cookbook?

Our friends in the band Air are very much a part of that French scene. They were friends with Daft Punk, Phoenix, and all those groups. The Moog Cookbook came out like two to three years before Daft Punk. We know that the Air guys heard it, because the Air guys hired the Moog Cookbook to make remixes for them. That’s how we ended up touring in their band.

Air didn’t have a backup band, and so when they reached out to [Brian and I] to do remixes, they asked if we knew any musicians. We said, ‘You don’t know any musicians in France?’ He goes, ‘Well, they’re not any good.’ So Brian and I said, ‘Well, we’ll be your backup band, and we’ll find a drummer and bass player for you.’

We got Brian Reitzell, who was in TV Eyes with us, and Justin Meldal-Johnsen on bass, and we became Air’s backup band. We were then hanging out in Paris with Air making their second record [10,000 Hz Legend]. They said, ‘Yeah, the Daft Punk guys saw your costumes, and we have a feeling that’s where they got the idea to wear masks, because they never wanted to be seen.’ They always wanted to be incognito. They had a lot more money for these very, very fancy masks. We had these simple Halloween costumes we found at the thrift store.

Those costumes are so bizarre, but that’s why I like it.

I wish there were more artists nowadays who enjoy being bizarre, who enjoy being not afraid to like, freak some shit out.

Did you have any trouble getting permission to do all these covers?

No. The way it works legally, unless you’re gonna change lyrics, [is that] you don’t have to get the artist’s permission. People can cover Beatles songs from now until the end of time. If they change the lyrics, they have to contact the Beatles publishing company and get permission to do that, and they might not be granted permission to do that. Those are the legalities of that. If you cover somebody’s song, the original artist collects most of the money on it. You don’t collect most of the money on it.

So on this album where you cover Weezer’s “Buddy Holly,” they collect on your music?

Weezer makes like 90 percent of the money, if there are generated sales from the Moog Cookbook cover of that.

They must be kind of psyched about that.

We actually know a couple guys in Weezer, and they were very complimentary about it. In fact, somebody told me they were opening their show, before they came onstage, they’d play the Moog Cookbook version.

Were there other musicians that were like ‘Hey, what the fuck, why are you covering this?’

No. We didn’t hear anything negative, really. We usually got a few compliments back. I talked to Billie Joe [Armstrong] from Green Day once, because Beck played a show with them. He said he really likes the cover that we did. But at first, he was really scared and frightened, because he said, ‘You guys took my song, and you turned it into elevator music. It scared me that I’d written a song that was like this light, weird elevator-music song.’ And he goes, ‘At first I didn’t like it because it scared me, that you took it there, and that I had created this monster.’ But then he goes, ‘The more I listened to it, I liked it.’ I really enjoyed that. I thought that was pretty funny.

Any word from Don Henley about covering “Hotel California?”

[Laughs] No. I haven’t heard from him.

I don’t know if you’d heard anything from Led Zeppelin. They’re probably not too receptive about the whole thing…

Actually, we heard from John Paul Jones, the bass player.

Oh! What did he have to say?

He’d been in Los Angeles a lot, and Brian, my partner, ran into him. I think John Paul Jones was producing a band Brian was friends with. So we got to meet John Paul Jones, and it did indeed come up that John Paul Jones had heard our version of it, and he was very complimentary – which was just the greatest news to hear in the world. He thought for all the goofiness and silliness, that it actually rocked out quite a bit. He was like ‘Yep, you guys captured the, you know, rock vibe of it, the way you did it with these electronics.’ So I thought that was pretty cool.

SOLO WORK

“You Were Right” – Solid State Warrior (2006)

“The Land of Pure Imagination” – Solid State Warrior (2006)

Why did those songs stand out for you?

[These songs are] very different. They show a lot of sides to what I was going for with those records. The solo albums are very much like Jellyfish, [in that] ideally they’re all very catchy and sing-along. They jump around stylistically; I explore a lot of different sounds and stuff within the rock pop world. If you’d listen to [Solid State Warrior] for the first time and the songs were back to back, you’d be like, ‘Is this the same group?’ But we were able to pull it off; and that’s something that we enjoyed doing. We felt we did well.

BONUS TRACKS:

LOGAN’S SANCTUARY SOUNDTRACK

“Islands in the Sky”

“Pleasure Dome 12”

We’ll just throw in an added bonus. Do you know I did an album with Brian Reitzell – the guy from TV Eyes, and the film composer guy? We did a fake soundtrack. It was an album called Logan’s Sanctuary.

I’d been doing remixes for a variety of artists, and this one record company had me do a lot of remixes for their artists. It went really well, and so they said ‘Hey, we’re going to do a series of fake soundtracks to movies that never existed.’ They were a pretty adventurous record company.

They said, ‘Let’s do a fake 70’s sci-fi movie soundtrack.’ And everybody’s like, ‘Well, you remember how great the movie Logan’s Run was?’ It was a pretty famous ‘70s sci-fi film, with a good soundtrack. It wasn’t like Logan’s Run II; it was called Logan’s Run Sanctuary and Brian and I thought that was a good idea. There was no actual film footage, so it definitely had a sound.

There was so much sci-fi stuff going on in the ‘70s. You know, ‘Here’s the future year 2000,’ and it’s nothing like what they were expecting. So why “Islands In the Sky” instead of say, “Pleasure Dome 12?”

Actually, “Pleasure Dome” is a better one, just to show people who may have never heard of it before. [The soundtrack] was us having fun with the whole progressive German synth work, from bands like Kraftwerk and stuff. We were very inspired by that, and Kraftwerk was just such a huge influence on all of us back in TV Eyes.