I regret to tell you that when I was in high school—skipping study hall to listen to my iPod Nano alone in one of the girls’ bathrooms—I graffitied “REVOLUTION GRRRL STYLE NOW” in Sharpie on a stall door once.

Like a total brat, I wrote a lot of things on those doors (a clunky rendition of the Black Flag logo perhaps the corniest among them), clearly with no regard for the efforts of the custodial staff of Libertyville High School. I may have had radical intentions, but certainly it’s antithetical to the riot grrrl ethos to make the job of a minimum wage worker any harder than it already is. But what outlet is there beyond the bathroom stall for the politically radical suburban teen?

I tried putting together a zine with my friend Erin—whom I’d befriended after discovering we both read Rookie—but we never managed to find an audience for her musings on the wage gap and mine on how cool the women in the original cast of SNL were. I posted flyers in the aforementioned girls’ room in an attempt at hosting an underground meetup for like-minded young feminists, but they were taken down by the end of the day (probably by the also aforementioned custodial staff) because I hadn’t had the foresight to get them approved by the school. So, like every other millennial who couldn’t find her tribe in the physical realm, I turned to the internet.

I hadn’t originally found Bikini Kill online—it was actually through a Nylon Magazine feature about how to dress like various riot grrrl and grunge icons. Even as a 14-year-old, I thought focusing on the artists’ appearances seemed counterintuitive to the little I knew about feminism, but it did prompt me to look up their music on YouTube, so mission accomplished, I guess. I don’t exactly remember the first Bikini Kill song I heard, but chances are my introduction was the top-search-hit fanmade music video for “Rebel Girl” that featured the track over archival footage of Maoist Internationalist dancers. (The video was uploaded 11 years ago and now has over four million views.) Not long after, I pirated The C.D. Version of the First Two Records, Pussy Whipped, and The Singles.

This was fin de aughts, when YouTube was still better known for being home to Keyboard Cat, Nyan Cat, and myriad other meme cats rather than being a rotting petri dish for the rhetoric of men’s rights activists and literal nazis. The micro-blogging site Tumblr hadn’t yet been bought by Yahoo, and was by far the social media platform with the most cool cred. It was the easiest medium to find (or build) a community based around your niche pop cultural interests. Following hashtags like #riotgrrrl or #bikinikill would lead you to blogs like Fuck Yeah Kathleen Hanna and the now tragically defunct little-trouble-girl, which were devoted to posting photos of Hanna as a teenager, or her posing with Joan Jett, along with scans of old issues of Bratmobile’s Girl Germs and Bikini Kill’s self-titled zine. From there, you’d find the personal blogs of other users, usually fellow teen girls, whose re-blogs often served to punctuate their own art and short essays on the frustrations and indignities of being a young woman. Tumblr in its salad days felt like a digital reconstruction of your own bedroom—collaged wall-to-wall with idols, crushes, and inspirations—and you were welcome to invite anyone over, not just the people who went to your high school, not just the people your parents approved of.

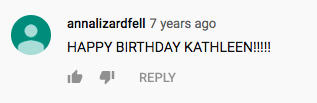

YouTube’s appeal was less personal, but it was invaluable as a resource. Buried beneath the viral videos, it was home to an unbelievable collection of musical ephemera, like old concert footage and forgotten demos digitized from fans’ old cassette collections. It was a living museum, the world’s most publicly accessible archive; it allowed not only for studying the work of the artists I already adored, but of discovering the work of their peers and predecessors via the informational Mobius strip that was the related videos section. (This was before it was tainted by The Algorithm and actually showed videos related to the one you were watching.) I’d spend my precious teenage nights clicking from the audio of “Pillowcase Kisser” by Skinned Teen, to a video of a 2010 performance at Joe’s Pub by Kathleen Hanna—in which she told the story of inspiring the name of Nirvana’s “Smells Like Teen Spirit”—to Huggy Bear performing “Her Jazz” on the UK music show The Word. I’d watch hours of footage of Bikini Kill concerts from the early ‘90s, including a clip of the band performing “Jigsaw Youth” on which, upon revisiting, I see that I apparently commented “HAPPY BIRTHDAY KATHLEEN!!!!!” seven years ago.

The comment sections of riot grrrl videos were surprisingly tame. You’d expect the sexist, homophobic vitriol YouTube commenters are infamous for to be amplified in the presence of radical feminist punk, but for the most part, the forum was populated by discussions of the music’s political themes, OG riot grrrls waxing nostalgic, and people discovering the music for the first time. (A personal favorite, from a user named SimplySum41: “I am just now discovering all these RIOT GRRRL bands… ive been asleep all my life…” 77 upvotes.)

The same sort of gentle digital community was fostered by Rookie, the online magazine founded by Tavi Gevinson with the help of former Sassy EIC and Gen X icon Jane Pratt. On a playlist dedicated to riot grrrl’s greatest hits, user redruby commented: “I just got into riot grrl a few months ago, and it seriously did change my life. Not many girls in my highschool identify themselves as feminists because they think it’s like a dirty word, but I do. Bikini Kill is honestly one of THE most badass bands ever, and they have a song for almost any issue a girl has ever been faced with. . . . I have a major girl crush on Kathleen Hanna.”

Rookie featured pieces on Hanna and riot grrrl at large alongside essays deconstructing the Spice Girls and the insidiousness of “girl hate.” It converted the movement into a format and language that was accessible and easily digestible for those unfamiliar not only with it, but sometimes with tenets of feminism in general. Even as a pretentious teen who’d already clocked in a couple years as a neo-riot grrrl by the time the site launched in 2011, I never felt spoken down to; rather, I felt validated at the thought of there being other girls scattered across the world (and time and space) who obsessed over things just as hard as I did.

People tend to think the intangibility of internet culture makes it more sterile and inauthentic than whatever The Way Shit Used To Be was. Corners of it like Rookie and Tumblr were responses to that idea, though probably more in the sense of that classic teenage paradox of feeling nostalgic for a time you didn’t live through rather than as an explicit rebuttal to it. Regardless, frequenting those digital spaces felt like being part of a real community. I discovered music and made connections with people I otherwise wouldn’t have; feminist art and ideology, which a decade earlier I probably would have only found on the off chance a zine was circulating in Libertyville, Illinois, was readily accessible to me and billions of other girls across the globe.

Not long after I graduated high school, the major players of the riot grrrl movement ascended to the relative mainstream. Carrie Brownstein’s Portlandia premiered in 2011, eventually catapulting her into a household name and preempting Sleater-Kinney’s massive comeback. The Punk Singer, Sini Anderson’s documentary about Kathleen Hanna’s life, career, and battle with Lyme disease came out in 2013 (I saw it in the theater with, by the grace of something, my new college friends who’d idolized Hanna as much as I had). It marked the beginning of her return to the spotlight, releasing new music with her band The Julie Ruin and, this year, reuniting with Bikini Kill. Maybe I’m projecting, but I can’t help but think that teen e-girls played at least a small part ushering in riot grrrl’s pop cultural revival.

Most of the videos I’d saved to playlists on my old YouTube account are now private, blocked in my country, or have been altogether deleted. (Never let an adult tell you that what you put on the internet will be there forever—I’ve lost too many cherished curios to the digital abyss for that to be true.) Sometimes I’ll revisit what’s left, and each time I feel like I dodged some sort of bullet by finding it all so early and so easily. The idea of knowing someone else IRL who had heard about riot grrrl, let alone cared about it as much as I did, seemed unthinkable in the hours I spent enrapt by the infinite scroll of my Tumblr dashboard.

Some people like to be precious about their niche interests, but I’m happy riot grrrl is even more accessible now. I’m glad that, at least in certain spheres, it’s mainstream—that its fearless leaders are getting their due, and that maybe radical teens won’t have to feel so totally trapped within the confines of their high school’s bathroom stalls anymore, though I’m sure that’s a futile hope for any generation. And at least on the internet, there’s unlimited room for girls at the front.