One of the great crimes of the 21st century is the semantic broadening of “nerd.” Are you an aficionado of Star Wars, the Marvel Extended Universe, Game of Thrones, Doctor Who, Fortnite, J.R.R. Tolkien, or Funko Pop? Congratulations, you’re… still just an aficionado, one that will likely never endure cyber or physical bullying for enjoying any of the aforementioned in 2019.

Affection for mainstream (or, in many of these cases, mainstreamed) art is not nerdom. Sure, language evolves, but Merriam-Webster is still spot-on in defining a nerd as “an unstylish, unattractive, or socially inept person.” Of course, the M-W entry goes on to elaborate, “especially: one slavishly devoted to intellectual or academic pursuits.” And that brings us to the subject of today’s bathroom read: Juggalos, to whom it appears we sadly cannot dub the last true nerds in pop culture after all.

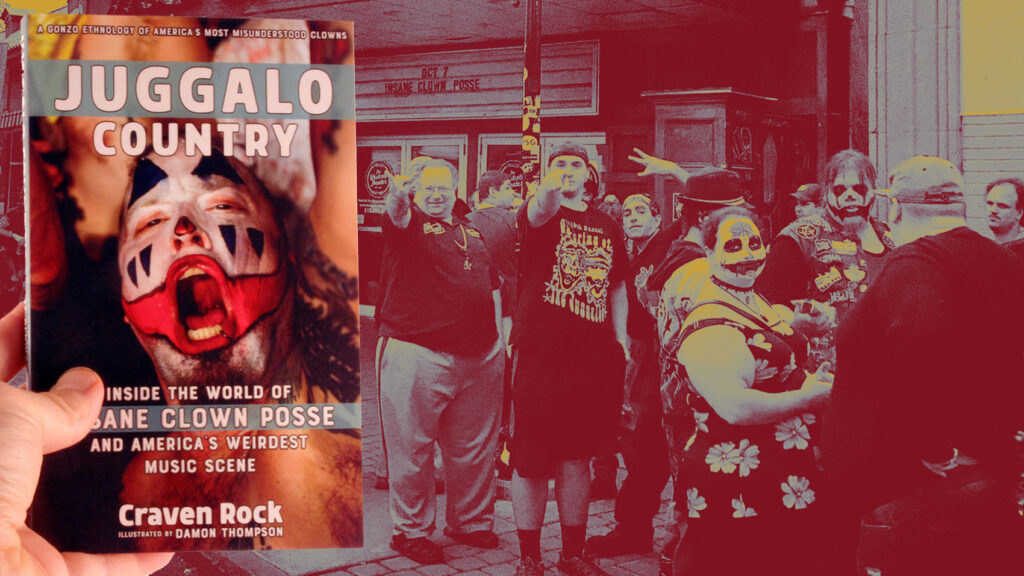

No offense to Insane Clown Posse fans (and very, very likely none taken) in the suggestion that they probably don’t start their morning commute by tuning in to Terry Gross on Fresh Air. But that’s kind of the point of new ethnography Juggalo Country (Microcosm), an open-minded first-person account of the annual, infamous Gathering of the Juggalos.

There’s a good chance you’re already sighing. It’s been a decade since not only the first of Saturday Night Live’s inspired parodies of the Gathering, but ICP’s insta-meme “Magnets” video—Juggalo fatigue is real. But maybe that’s because we’ve been overexposed to the wrong kind of first-person accounts: hipster elites infiltrating the Gathering to chortle at the uneducated, slovenly masses who inexplicably devote their lives to the worst hip-hop—if not culture at large—has to offer. Juggalo Country author Craven Rock (yes, it’s a pseudonym) offers a refreshingly different perspective from the get-go. His teenage punk rock awakening in rural Kentucky is a familiar story—the music empowered and politicized him, as it has countless others—but Rock’s modest small town, middle American upbringing affords more empathy toward Juggalos than derision.

“That pissed off energy from my youth makes me think of the ire and condescension punks and others in counterculture exhibit toward the mere mention of Juggalos, and I can’t help feeling it’s a bit ironic,” he writes. “I, too, find the whole Juggalo aesthetic to be distasteful, from the sophomoric toilet humor of [self-ascribed subgenre] Wicked Shit to the eyesore aesthetics of Hatchet Gear [Psychopathic Records’ clothing line] fashion. More importantly, on an ethical level, I’m grossed out by the materialism, misogyny, and anti-intellectualism prevalent in Juggalo culture. But I can’t help empathizing with the Juggalos. If I don’t understand what Juggalos do, I think I can understand why they do it.”

When we reach Rock via email, he politely demurs regarding his rationale for the nom de plume, the same he’s been utilizing since his zine-writing days. Both Microcosm and Google are largely dead-ends for biographical nuggets, but he reveals that “I’ve also been a punk rocker, cab driver, an activist, a dishwasher, as well as many other things,” the latter including an advocate for Mutual Aid Disaster Relief and, most recently, a forest firefighting trainee. Juggalo Country was initially published on a friend’s small press in late 2013 under the title Nights and Days in a Dark Carnival, and Rock is grateful that Portland-based boutique Microcosm gave it a second chance to find its audience. A new introductory chapter focuses on the Juggalos’ 3,000-strong march to Washington, D.C. in 2017 to protest being labeled a “hybrid gang” by the FBI, as well as the slow, but encouraging uptick in feminism at “the only place I’ve ever been where I’ve seen 11-year-olds watching women oil wrestling without anybody thinking anything of it.”

As to the main narrative, just as his subjects were becoming household names, Rock bribed his best friend Damon Thompson (the book’s illustrator) to accompany him to the 11th annual Gathering at Cave-In-Rock, Illinois. Their encounters over that long, scorching weekend are captured in Thompson’s stark black-and-white renderings, an interestingly unconventional choice for an event that seems ripe for photographic documentation.

“I think when we live in peak society of the spectacle, images like photos become ubiquitous and meaningless,” Rock counters. “Photos seem common and cheap, taken on phones and loaded on Instagram. There’s nothing of humanity in them anymore. So, I went with Damon’s illustrations, which I feel take on more symbolism and depth.”

Rock is honest about his inconsistent journalistic approach throughout the book. Upon striking up an early conversation with a friendly, hip non-Juggalo couple from Portland, he hisses at Thompson to “get rid of them.” The author wants total immersion, to communicate with natives only. But he eventually acknowledges the value in meeting the couple, who brief them on the Gathering’s wilder attractions; after all, he and Thompson can’t be everywhere at once.

Once they do mingle, Thompson’s Misfits shirt is met with almost universal derision. And it’s not because the attendees think Violent J and Shaggy 2 Dope can bench more than Glenn and Jerry—it’s simply because the Misfits are not a Psychopathic Records band. Artists not on Psychopathic: how do they work?

Which leads to Juggalo Country’s thematic undercurrent: This is a subculture exclusively devoted to whatever Insane Clown Posse produces and endorses, almost entirely without exception. The six Joker Cards, the Dark Carnival, Twiztid, Big Money Rustlas, Faygo—it’s gospel, but why? Maybe because the rest of the world perceives Juggalos as losers, violent assholes, dumbasses, white trash, scrubs… even nerds. It’s not hard to imagine them catching shit for rocking Hatchet Gear in public; it’s not hard to imagine blows traded in a cafeteria or library. So like many marginalized subsets do, they gravitate to family, to the collective, perhaps to the comfortable insulation of the hive mind.

Which is a great thing when they have each other’s backs, helping the author stay upright on the brink of blackout collapse in triple digit heat. And less of a great thing when women are not only objectified, but bottled onstage: Tila Tequila’s infamous Gathering debacle is referenced here, and Rock’s take is intriguing: “Nobody deserves to get rocks thrown at them, but like most of the Juggalos, we find it morbidly funny. I carry about as much sympathy for her as I would any other richie… Tom Cruise… Paris Hilton… Bret Michaels. Hell, I’d laugh if any of them got pelted with shit and rocks. I view them all as enemies of the people. Coming up in punk, we also hold the mainstream in contempt—for the wealth, power, and spectacle. We come at it from different angles, but the Juggalos and punks both despise mainstream culture for similar reasons.”

And there’s the rub. Some of the most vital and beautiful outgrowths of punk rock are social consciousness, progressive ideals, fiery activism. These are not traits that the Juggalos share en masse, but Rock spends the final chapter hopped up on whiskey, pot, and Vicodin, watching the headliner and ruminating on his subjects’ potential: “I wonder how things would be if the Juggalos were given something beside Hatchet Gear and Psychopathic Records. I wonder what would happen if they broke free of the spell of Violent J and Shaggy 2 Dope and grabbed hold of their own power. Would they return to the Dark Carnival? Would they still be distracted by the prophecies, the wet T-shirt contests, and the Flashlight Wrestling? Would they plant a garden instead of eating elephant ears and drinking Faygo? Would they wave their hatchets at their oppressors? Would they get an education or simply educate themselves?”

That revolution was not to be televised. Not in 2010 and so far absolutely not in 2019, despite those aforementioned baby steps of feminist progress. But maybe for something as perpetually inscrutable as Juggalo culture, baby steps are all that matter. “What I took away from the Gathering was that Juggalos… took care of each other, were kind to each other and were a family,” Rock concludes. “Through their strength together, they could rise above the hate and oppression they got from the outside world. In spite of the commercialism and the top-down leadership of ICP, this is a beautiful thing.”