No matter how “adult” one may feel, a great many of us are prone to a nostalgic rush whenever we walk through the toy section of a department store. This excitement is baldly consumerist, but that’s not to say it isn’t informed by true emotion. Hell, no small part of our ability to connect to each other in the last 50 years has been informed by the toys we had—I, for my part, have carried an oversized Spider-Man action figure with me like a talisman for over 25 years, imbuing it with personal weight well beyond ToyBiz’s initial intentions as I go.

As Millennials and Generation X settle into getting older, that connection to consumer products of our youth has yielded an uptick in smaller-run toys—as Super7’s Brian Flynn refers to them, “arthouse toys”—whose target demographic is largely adults who were shaped by their experiences with mass-market toys in the 1970s–1990s. As with the vinyl revival in music, these specialty toys can feel like the realization of once-distant plastic dreams: Super7’s decision, for instance, to make Masters of the Universe toys in 3 ¾” style, so that they might finally share adventures with G.I. Joe and Luke Skywalker, seems like an inevitability that simply came 25 years too late.

To better understand this phenomenon, Riot Fest talked to some of the folks working in the arthouse toy industry. All of these people work the game on different levels, and for divergent reasons, but they all share a passion for the toys and popular culture of their youth, and for finding new ways to connect to other people’s experiences with same.

THE BIG BUSINESS: NECA

The National Entertainment Collectibles Association is a pretty large, established business. They’ve got subsidiaries and everything. They know their target demographics; they’re very strategic about their licensing.

Still, for NECA’s Director of Product Development Randy Falk, this is not a cynical endeavor, but something which comes from a place of earnest excitement. His favorite focus group, all told, is his own kids: “My daughters love our Darth Vader Clapper. It’s been in their bedroom since November.”

It’s not terrifically challenging, of course, to sell anything related to Star Wars, but we came to NECA more curious about some of their more offbeat toy licenses. They’ve made a big splash recently with a run of Golden Girls action figures; since purchasing Joseph Enterprises, creators of home-kitsch staples like Chia Pets and The Clapper, they’ve also released Chia heads of Blanche, Dorothy, Rose, and Sophia, as well as the aforementioned Darth Vader Clapper.

Another offbeat item NECA has created is an action figure in the style of the late, beloved public TV painting show host/perennial pop culture phenomenon Bob Ross (Joseph Enterprises had already dropped a Bob Ross Chia Pet by the time they bought the company). To hear Falk tell it, though, this was among their safer bets. “You know, with Bob Ross, it was an educated guess, because there’d been a lot of t-shirts and bobbleheads. We realized that there’s a bigger, broader following for Bob now; if people didn’t watch it growing up, they might still be watching it on Netflix, chillin’ out and listening to his voice. Really, doing Bob Ross stuff is low-risk!”

Of course, that casual attitude might come from the fact that NECA’s done much more surprising things, most of which were met with success. “In the early 2000s, we did a program with Cheech & Chong, which included stash jars that were busts of their heads. You could remove Cheech’s hat or the top of Chong’s head (from the bandanna up) and put your stash under it. We made the “Pussy Wagon” key ring from Kill Bill, a full-sized replica of the leg lamp from A Christmas Story... our core is the collectible action figures, but we do a lot of stuff that’s outside the box that reaches into the kinds of audience that would never buy an action figure.”

This is not to say, though, that every risk is greeted cavalierly. Two of Falk’s personal toy dreams, both of which are surely shared by a good chunk of Riot Fest readers, have thus far gone unfulfilled. “The top of the list would be Mike Tyson’s Punch Out: I’d love to have toys of all the fighters, and I think they’d be a blast. I’m also a huge fan of The Young Ones, and I’d love to make toys of those characters. There’s probably not a big enough audience, but I’ve loved that show for 30+ years.”

THE PUNKS: SUPER7

The difference between Falk and Super7 founder Brian Flynn? As long as he can get the license, there’s not much that will stop Flynn from making the exact toys he wants, marketability be damned. If he wanted Young Ones action figures, by God, he’d make it happen.

“We really try to make sure that the thing we make is a thing we would buy; it’s not necessarily the smartest, most popular version, but it’s the version that’s most interesting to us,” Flynn explains. “If it doesn’t work, and I’m gonna get stuck with a warehouse of 10,000 of these, I don’t want to go in there and see something I didn’t want to make in the first place. I’d rather go down and say ‘Well, it didn’t work, but fuck, this is the coolest thing in the world.’”

Lucky for Flynn that Super7 has found plenty of people who want the same stuff he does. The company started humbly in 2001, as a fanzine about Japanese toys. Each issue would come with a coupon which could be sent in to receive an exclusive “recolor,” a phenomenon long popular in Japan where action figures are given a variant paint job.

Super7’s approach, however, was a little different from that of the older Japanese magazines like Figure King or Hyper Hobby. “Japanese collectors tend to be very analytical and data-driven, so when they’d do recolors, they were very referential to specific things from the past, like ‘This time, we’re making it in ‘55 Godzilla blue.’ We approached colorways from a strictly aesthetic perspective, because a lot of the American toy collectors don’t know the source material, and are just looking at the toys in a vacuum. They would look at things for their design and colors, and appreciate that it’s the craziest thing ever; they had no frame of reference beyond that.”

“One of our first toys was a ‘Meltdown Hedorah,’ in translucent orange with red and yellow highlights. Some people wanted to know what it meant and or where it came from, but we were just like, ‘It looks cool. What else do you need? It’s fucking badass!’”

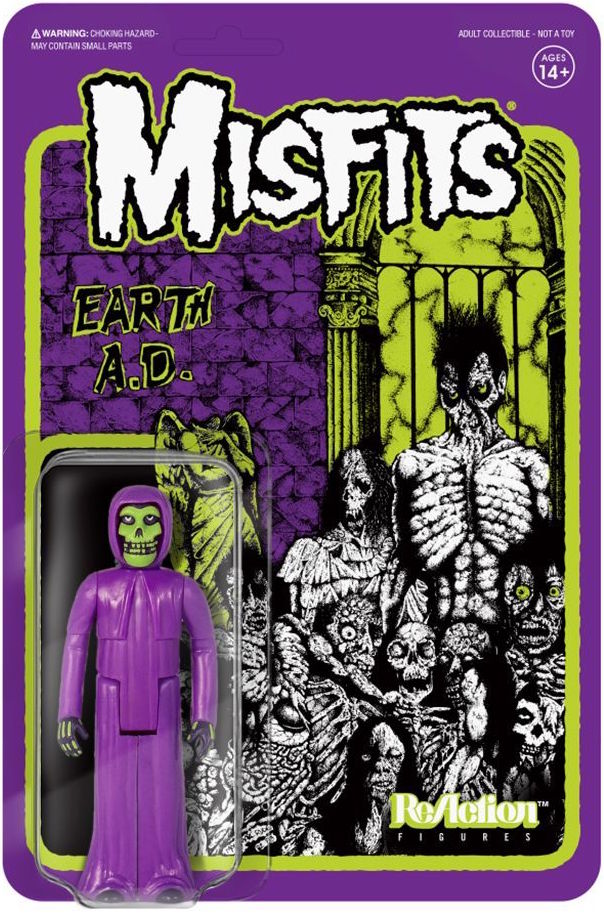

The magazine folded in 2007, and from there became a “mook” (half magazine/half book), a store, a maker of limited vinyl toys in collaboration with Japanese toymakers, and finally a company with its own in-house design, manufacturing, and distribution. Nowadays, Super7 works with big licenses like Masters of the Universe and Alien, but they still do things exactly as they want them. This manifests itself as a “slime-pit” He-Man, Iron Maiden M.U.S.C.L.E. figures, their original all-villain line The Worst, and half a dozen variant action figures of Misfits mascot The Fiend, among myriad other wild choices.

This has all been rabidly gobbled up by fans. Through all the success, though, Super7 has maintained the punk attitude which has informed them from the outset. Flynn, for his part, still finds it “mind-boggling” that he’s getting away with it. “The fact that we’ve been able to do this, and be successful while still making the weirder things we want to make, is great. It’s something that I never would have guessed we’d be able to do, though I’m more than happy that we are.”

THE ARTIST: THE SUCKLORD

Super7 was borne from the desires of one guy and his toy collector friends, but The Sucklord’s approach to toymaking is even more personal. Born Morgan Phillips, The Sucklord (a.k.a. Super Sucklord, head of the Suckadelic empire) has been recognized as a prolific “appropriation artist” since the release (under the name Supergenius) of his album Star Wars Breakbeats in 1998—but his dive into handmade mashup action figures is the work on which much of his reputation lies. It’s gotten him on reality shows (Work of Art: The Next Great Artist and Gallery Girls), and it’s won him some attention in rarefied corners of the art world.

He’s quick to downplay the “high art” aspect, though, unless there’s money to be made playing that card. “When you work on something all day, every day for years, it’s serious to you, so of course you want to have it taken seriously by other people,” Sucklord says. “On the other hand, in order to inoculate yourself from the disappointment of failure, so you put forth these assertions that it’s less than [fine art], to protect yourself when you don’t achieve the greatest level of artistic achievement.”

“Also, you want to keep your audience broad as possible, and not every kid gives a shit about art, and not everyone wants to buy art,” he continues. “Some people just want to buy something stupid and irreverent that makes them laugh, and some people want levels and levels of meaning. I pivot depending on the customer.”

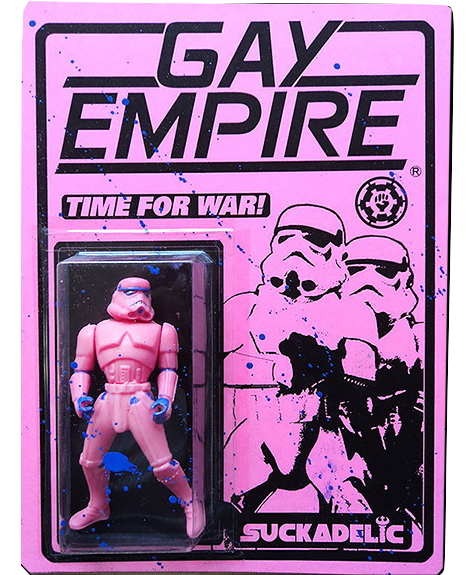

The Sucklord’s toys are sideways subversions of their source material: gay Stormtroopers painted hot pink, business suit-wearing Decepticons in blister packs emblazoned with the words “OCCUPY CYBERTRON,” Thundercats with hamburgers and hot dogs for heads. These items, handmade and sometimes one of a kind, don’t come as cheap as toys from the other people discussed here, but they’re also reflective of a more complex sensibility.

“I like the Super7 stuff, but they’re also just doing direct representational depictions of established properties. My inclination is to invert it it in a way that does something other than just present it as-is,” he explains. “There are also people like Dano Brown, whose whole schtick is to make a toy that of something that has no reason to be a toy, in a blister-pack with a photo of the thing. I’d rather play in that realm and make something that doesn’t make sense being a toy, but is also subject to further interpretation. I take one thing from one place, another from another, and by putting them together, I make something that neither of those things represent on their own.”

The fixation on action figures, though, started in much the same way as that of the others profiled here. “The four cantina aliens in the second wave of the original Star Wars action figure line are some of the most influential, transformational toys ever created, at least in my experience,” Sucklord says. “The first wave was all the obvious principal characters who were important to the play value, but the second round was all the dudes who’d been on camera in the background for one second, weird aliens who didn’t participate in the story in any way. They were fuckin’ beautiful and weird and cool… they didn’t need to exist, but they did, and that blew my mind as a kid. It made me realize, at least on a subconscious level, that if fuckin’ Hammerhead can be a figure, anything can be. That put me on the road to make my own stuff.”

“I wanted to make my own Greedo figure, so I took a bar of soap, got it wet so it was soft, and smooshed the figure into the soap. Then, I melted a green crayon on the radiator and poured it into the soap mold to make a reproduction. It was an utter failure — I couldn’t get the wax out of the soap — but for some reason, that motivated me to do this thing.”

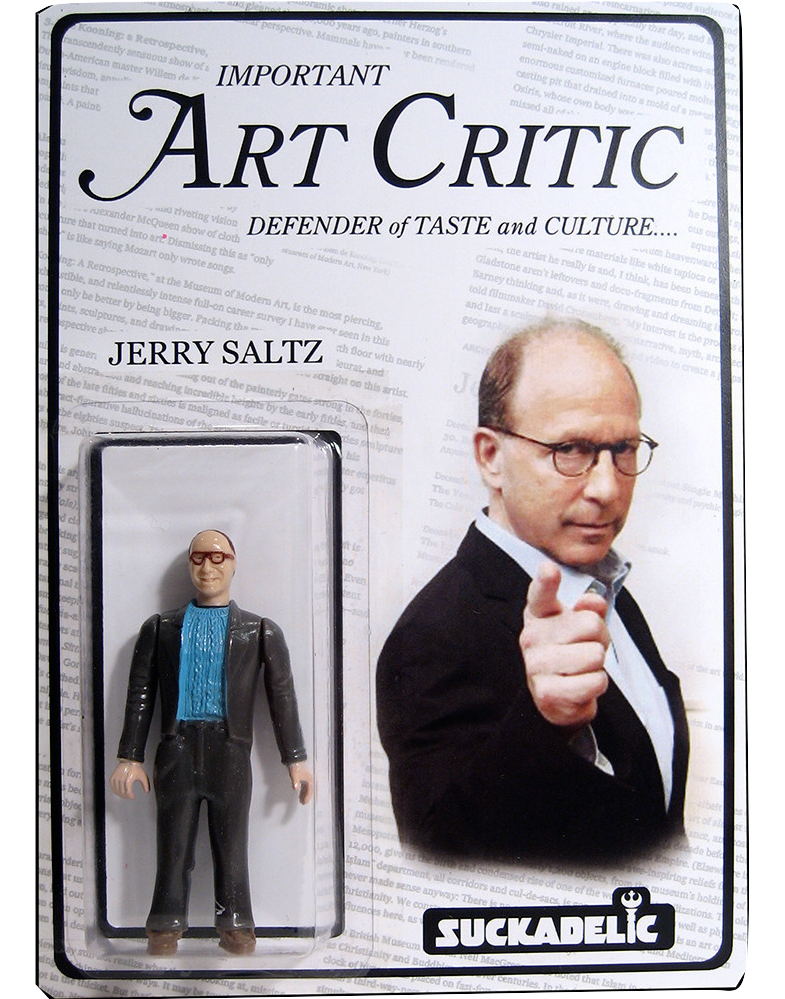

As with many appropriation artists, The Sucklord has had a contentious relationship with the “serious” art world. While competing on Work of Art, he found himself in the crosshairs of one of the judges, New York art critic Jerry Saltz; Sucklord had the last laugh, immortalizing Saltz as an “Important Art Critic” action figure, but that doesn’t mean the antagonism didn’t sting. “Saltz was very smart: he didn’t care for me, and it was his intention to get me eliminated from the show. Whether it was conscious or not, he found my achilles heel, and said ‘I don’t want to see you use any more fuckin’ Star Wars.’ With anyone who does appropriation work, you’re always constantly asking yourself if they really like you, or if they just like the thing you’re stealing from. It creates a certain dependency.”

“In retrospect, I wish I would have just said ‘Fuck you, this is what I do, and I’m going to do it even if you eliminate me,’ but I didn’t want to get eliminated from the show,” Sucklord concludes. “So I did what the art critic said—which is not something I’d normally do in real life.”

Still, there is hope for broader critical acceptance—though if certain people are to be believed, it might be a way off. “I had a psychic read me recently, and she said that my work isn’t really going to be considered important and meaningful until seven generations from now. If it’s gonna take ‘em that long to figure out, I just have to let go of my assumptions and let it live. I should just make whatever feels correct, and let the world sort it out, and the world’s fuckin’ stupid, so I shouldn’t get my feelings hurt if they get it wrong.”