I can’t seem to get through one October without remembering the Hex Girls. They appear in my memory, thrashing and jewel-toned, spiky-haired and sneering. I can see myself watching them in the TV room of my childhood home, the cartoon stretching across the arched screen of the black box, the palms of my hands getting itchy from resting on the carpet. There’s an image in my memory of me and my mom in the aisles of an Oak Park Target, trying to orchestrate a costume for Thorn, the lead singer. The errand was abandoned for some reason or another—I was just a plain old witch instead. I’ve since thought about dressing up as the band as a whole, but have never managed to lasso two friends into completing the trifecta. And October or not, their lyrics swirl around in my head: I’m a Hex Girl, and I’m gonna put a spell on you.

I’m not sure when I first watched the direct-to-video movie Scooby-Doo and the Witch’s Ghost in which they first appeared. It all blurs together in a childhood haze of VHS tapes and Cartoon Network marathons, but it’s quintessential: the Mystery Gang investigates a haunted colonial town, sees eponymous witch’s ghost, and in between butter-churning and autumnal festivity, save the day. But who cares about some witch and her ghost—the Hex Girls are here!

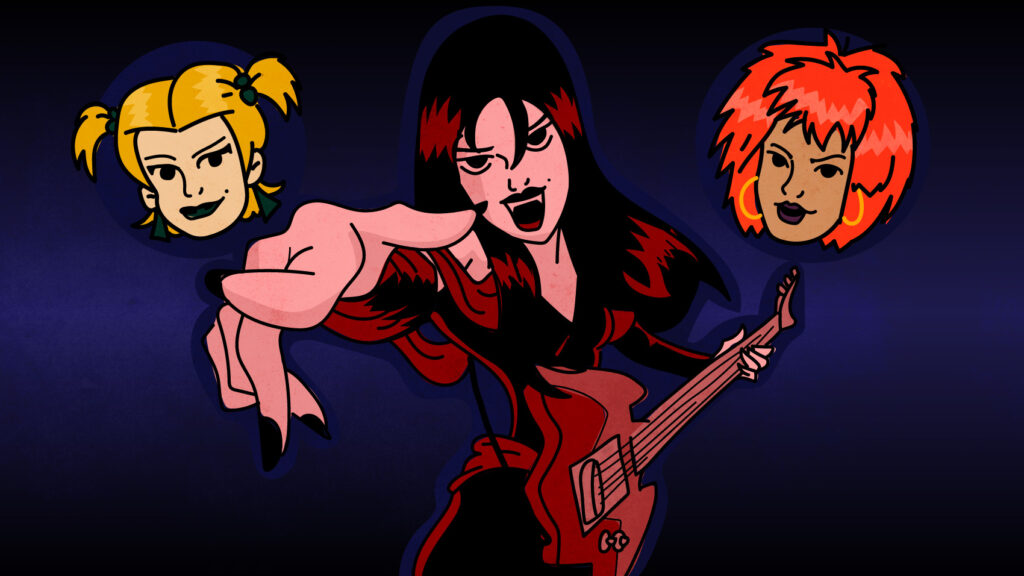

Fred and Shaggy thought the same when they first stumbled upon the trio, eyes wide and mouths agape in the way of enchanted cartoon men. I would chide them for their objectification were I not so similarly enamored: their black lipstick, their musical talents, the way they seemed so carelessly cool. They were goth in an essential late-90s way, like The Craft and Faith in Buffy the Vampire Slayer; Aesthetically, they encapsulate every goth trend of the 90s: studded chokers, dyed hair, heavy eyeliner. And they’re a band—the agency from which carries them over the threshold from passively admirable to actively motivational.

You can watch any of their performances (see: bootlegged movie clips) on YouTube. The way the viewer is introduced to the band mirrors that of the Scooby Gang—celestially and near-divinely appearing in a cloud of fog machine smoke after emerging from the woods. Thorn taps a heeled foot and shreds her bat-shaped electric guitar. The whole thing is so perfectly performative: the hands twisting as if conjuring a spirit, the vampire fangs. I’m nearly reminded of Soccer Mommy’s Sophie Allison, who coincidentally has tweeted about procuring fangs for herself. The songs are produced fairly simply, just electric guitar, bass, and drums—maybe it’s because this movie was direct-to-video, but part of me feels it’s all that is needed. (The red-headed Luna plays keyboards in the background that are non-existent sonically—and yet, I’m unbothered!)

The Hex Girls define themselves as eco-goth, in an absolutely beautiful line that I cannot believe was written into the script: “We’re eco-goths / and we don’t need your approval.” No, you do not! (But I’ll give it to you anyway.) In “Earth, Wind, Fire and Air,” Thorn kind of sounds like Sleater-Kinney’s Carrie Brownstein, exaggeratedly throaty and bellowing. The heavy chords of the chorus are supplemented by jangly strums in the verses and a very clear tambourine. Dusk and Luna shout phrases back in the style of punk gang vocals. The song is melodic in the manners of Veruca Salt and Letters to Cleo, and it achieves this because it’s both genre-d and nonspecific—an osmosis of popular rock music at the time of its conception.

But unlike Josie and the Pussycats, which was released two years later and soundtracked by Kay Hanley, the Hex Girls’ music was not written by a pop-punk icon, or even anyone in the music industry; the songs were crafted by men who wrote TV and movie scores—and it shows. In this way it reminds me of the Buffy theme song, a lot of jumpy shredding and emphatic drums with very little direction or goal aside from exciting viewers and getting them in the mood.

Some may argue that the melodic pop sensibilities of the Hex Girls make them dishonorably palatable, a diluted version of the 90s punk contemporaries they were attempting to emulate. (Here is where I remind myself that they’re characters that bend to the will of screenwriters.) But I think if they were making music today—and, you know, real—the Hex Girls could feasibly appear on a lineup with Daddy Issues or Tancred or Bleached, women who are defining (pop) punk today.

The Hex Girls got me jumping with them, putting on dark lipstick and wanting to play an instrument. What the Hex Girls shared with Josie & the Pussycats, if not skilled songwriting, was a subverted embrace of femininity, that which wasn’t Cher in Clueless or any girl post-makeover montage. They were fun and spunky and non-competitive and kind. When I was watching Scooby-Doo, somewhere between the ages of five and nine, I wasn’t looking for musical ingenuity or innovation. As a kid, I just needed something to exhilarate me.

When I think of the Hex Girls now, I get a similar sensation—one of amorphous inspiration, that brand of unspecified wanting. It’s that yearning of being a kid and longing to be something. At six, I reacted by approximating makeup and clothing in its most appropriate form: Halloween. In my 21st year, I’m neither musician nor goth, and I still kind of want your approval. But I don’t think the Hex Girls care if I’m anything in particular as long as I’m excited and excitable, and take them at their word, as they dissolve back into machine-produced smoke.