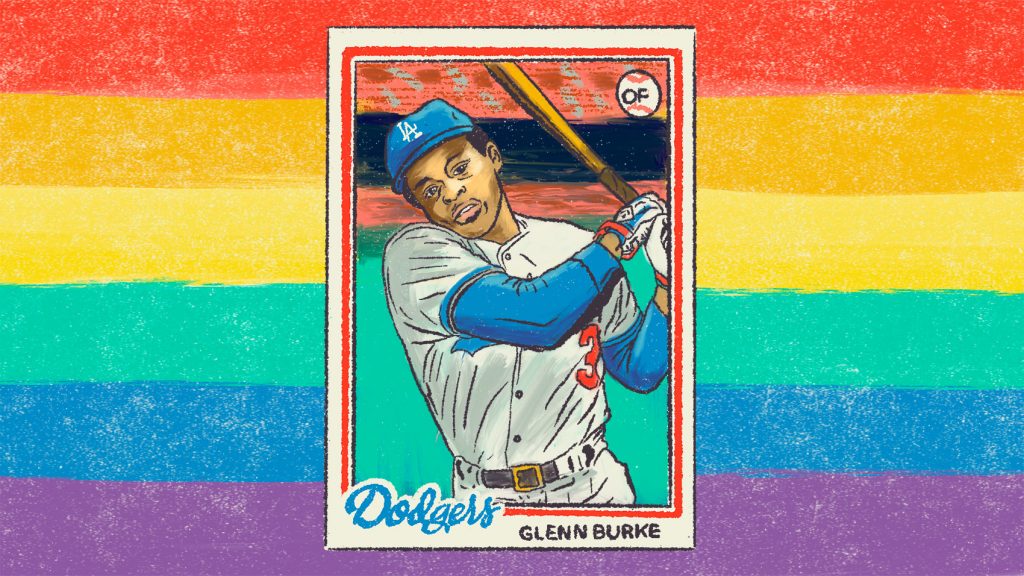

If one were to judge him solely on his MLB statistics, the late Glenn Burke would seem like just another ballplayer who couldn’t quite cut it in the big leagues. An outfielder who played parts of four seasons for the Dodgers and A’s during the second half of the 1970s, Burke had good speed—as evidenced by his 35 stolen bases in just 225 games—but his .237 batting average and limited power production would seem to indicate why his career was finished by the time he turned 27.

But Glenn Burke was quite a remarkable ballplayer, even if his numbers don’t really tell the story. An intense competitor with a wicked sense of humor, Burke was the quintessential “good clubhouse guy,” the sort of consistently upbeat player who could keep his team loose through the stress of a pennant race via an extensive arsenal of jokes, vocal imitations and dance moves. Burke demonstrated the same sort of charming ebullience on the field, as well: On October 2, 1977, he congratulated teammate Dusty Baker on his 30th home run of the season by greeting him at the plate with an upraised palm; Baker reached up and slapped it, connecting for what’s generally believed to be the first “high five” ever seen on a big league diamond.

Burke was more than just a footnote in the history of home plate celebrations, however. Though he didn’t officially “come out” to the media until after his playing days were over, Burke was fairly open about his homosexuality during his time in the majors, something which ultimately proved extremely detrimental to his career. While none of his Dodgers teammates seemed to have an issue with him being gay—in fact, Burke may have been the most well-liked player on the 1977 NL Championship-winning LA squad—skipper Tom Lasorda (whose son was close friends with Glenn) and the team’s front office were far less accepting of his orientation. Worried that an openly gay player would be “a distraction” to the team, Dodgers Vice President Al Campanis offered Burke $75,000 to marry a woman. When Burke refused to go along with the charade, the team traded him to Oakland—and once the virulently homophobic Billy Martin took over as A’s manager, Burke’s MLB days were numbered.

Singled Out: The True Story of Glenn Burke, a new book from award-winning author and sportswriter Andrew Maraniss, is the sort of book you can’t put down even while it’s breaking your heart. Maraniss recounts both Burke’s struggles and triumphs—on the field and off—painting a vivid picture of a man whose considerable talents and personal magnetism were ultimately no match for prejudice, disease and drug addiction. (Burke, who also won medals in track events at the 1982 Gay Games, went into serious personal and physical decline after being hit by a car on the streets of San Francisco in 1987. He died of AIDS complications in 1995.)

Singled Out puts Burke’s life and career in a greater social and cultural context, exploring the Gay Liberation movement of the 1970s and its impact on San Francisco, the city that Burke called home during the off-season and following his retirement. Maraniss also recounts how San Francisco’s gay community was devastated by the 1978 murder of local politician and gay icon Harvey Milk and the AIDS epidemic of the 1980s. Much like Milk (whose killer Dan White was recently back in the news, via revelations that Fox News potatohead Tucker Carlson claimed to be a member of the “Dan White Society” in his college yearbook), Burke was an LGBTQ hero whose life was cruelly and unfairly truncated, but who remained true to himself to the end despite intense cultural and societal pressure to do otherwise.

RIOT FEST: What made you want to write about Glenn Burke?

ANDREW MARANISS: I’m trying to develop a little bit of a niche of books that are sports non-fiction with a social justice angle to them. My first book was Strong Inside, a biography of Perry Wallace, who was the first black basketball player in the SEC. Then I wrote Games of Deception about the first US men’s Olympic basketball team competing at the Nazi Olympics of 1936. I was talking to my agent about what I should do for my next story, and he actually said, “Well, what about Glenn Burke?”

I was born in 1970, so the late Seventies, early Eighties was kind of my wheelhouse, as far as being a fan as a kid. But I just knew the ‘top line’ sort of items about Glenn—you know, that he was considered the first openly gay player as well as the inventor of the high-five. And I didn’t know anything else about him, but I thought, “Well, that would make a great book, because you could tell it in the context of the Gay Rights movement in the Seventies.” Also, my books are considered young adult books, and I thought that teenagers were definitely ready for this story, more so than probably at any point in my lifetime—and, in some ways, more ready for it than a lot of adults are right now.

Glenn is considered the first openly gay MLB player, but it’s more complex than that. It wasn’t like he was giving interviews at the time saying, “I’m gay”—and though he wasn’t at all ashamed of his sexuality, your book makes it clear that he was still very self-conscious about it, and was worried about making his teammates uncomfortable.

Yeah. I would agree, and you see different shades of that through his minor league career when he’s sort of discovering his sexuality and asking himself, “How am I going to survive this?” And initially he says, “I’m going to have to hit over .300 and steal a hundred bases, and then nobody can say shit to me when they find out.” And then later he’s a little bit more ambivalent about it and thinks, “Well, maybe I should just be mediocre and keep the spotlight off myself, so I’ll be more anonymous.”

Which is a pretty profound (and profoundly sad) moment in your book — him seriously considering the notion of “Maybe I should just go along to get along.”

Yeah. It’s really sad. You wonder how many people around us, both then and now, have had that same thought. Homophobia has denied so many people their own greatness, and denied their greatness to the rest of us as well. But during the off-season, Glenn was living the life that he wanted to; living in the Castro in San Francisco, he was free and accepted. But even in the minor leagues, he invited his friend and teammate Marvin Webb over to his room at the Y, when it was pretty obvious that he had a boyfriend staying there with him from California. So he wasn’t hiding, and I think he was run out of the game because of who he was. Some people would say he quit or he played himself out of the game, that his statistics weren’t terrific. But given the lack of support that he had, and the fact that he was always looking over his shoulder in such a tough play game to play, I think that made it difficult for him to live up to his potential and become the player he should have been.

Your book makes a good case for Glenn being a much better athlete than his stats would suggest.

He was great athlete, and a phenomenal basketball player as well; I think he considered himself a basketball player first and foremost. But he set stolen base records at two different minor league levels, and his baseball teammates marveled at his physique, how strong and fast he was—Dusty Baker said he got the best jump on a ball in centerfield he’d ever seen, and Dodgers coach Junior Gilliam thought he had the potential to be the next Willie Mays.

A lot of baseball players need time to develop, even after they make it to the majors. But it’s clear that Glenn was never really given the chance to do that.

I mean, he starts two games in the NLCS in 1977, and starts one game of the World Series, so that would tell you that the franchise has confidence in this player, right? But when he doesn’t go along with the Dodgers’ bribery scheme, they almost immediately turn around and trade him. So he never really gets that “everyday” shot with the Dodgers that he probably earned, and he certainly doesn’t get it with the A’s after Billy Martin gets there. I think that there was a place for a player of his skill set in the National League back then; you didn’t have to hit 30-40 home runs to be a starting outfielder. Dusty Baker, who is someone I admire and obviously trust in terms of baseball wisdom and instincts, says he felt that Glenn was really coming along before it was all suddenly cut off.

I knew Dusty and Glenn were tight, but I was surprised to read how much other players on the Dodgers like Davey Lopes and Steve Garvey really loved Glenn and valued him as a teammate.

That was probably most surprising thing for me to discover when I was doing the research: That a rookie fourth outfielder was the most popular player in that clubhouse. That really says so much about how charismatic, funny and loose Glenn was. Don Sutton and Steve Garvey hated each other, but they were both crying at their lockers when Glenn was traded, and that says so much right there as well.

It’s fascinating to really see just how hypocritical the Dodgers were in their treatment of Glenn. They’re worried about him being “a distraction,” and meanwhile you’ve got Steve Garvey pissing off his teammates by pretending to be “Mr. Clean” for the press, even though he’s chasing women in every town.

Right. There was this quote from Tommy Lasorda about how if Steve Garvey showed up to take his daughter out for a date, he’d lock him in the house and never let him leave because he was Mr. All-American. But then Lasorda’s gay son is friends with Glenn, and Glenn gets traded because of it. And really, what team had more distractions than the Dodgers? Lasorda was bringing Don Rickles and Frank Sinatra into the clubhouse before games! Glenn was the least distracting part of that team, and the most popular player.

For me, one of the most powerful scenes in the book is the part where Bobby Glasser, a young A’s fan, witnesses a heckler raining one homophobic slur after another on Glenn during a game in Oakland, and then watches Glenn beat the shit out of the guy in the parking lot afterwards. On the one hand, players aren’t supposed to go after fans like that — it’s kind of Ty Cobb territory — but on the other hand, I found myself rooting for Glenn to kick the guy’s ass.

That scene is in the book thanks to the kindness of Erik Sherman, who wrote Glenn’s autobiography Out at Home with him while Glenn was dying. After that book came out, Erik started to get some letters from readers who had their own Glenn stories to tell, and Bobby Glasser was one of them. When I went and spent a day with Erik as I was researching this book, he gave me Bobby’s letter and was like, “You should get in touch with this guy.” It turns out that Bobby Glasser is now sort of a Glenn Burke collector; he’s got all his cards and some other memorabilia, and he makes custom Glenn Burke jerseys. He told me the whole story. That moment had such a profound impact on him, and as a result he’s really devoted his life in a lot of ways to memorializing Glenn.

Yeah, I could see how that would make a profound impression.

I mean, you’re at a game with your grandma, and all of a sudden you’re seeing one of the A’s beating somebody up in the parking lot! [laughs] I didn’t really think about it from the perspective of, you know, Glenn shouldn’t be beating up the fan. I felt anguish for Glenn that it had come to that, but I didn’t condemn him at all for doing it.

The tragedy of Glenn Burke’s life is so multi-layered. Even when you’re reading about him enjoying a few years of happiness in San Francisco, it’s like watching a slow-motion traffic accident because you know that AIDS and crack are about to completely decimate the city, and his own life along with it.

That traffic accident analogy is interesting because that was actually part of his downfall — he was hit by a car. But yeah, I think in some ways it’s a cautionary tale for any athlete; he had a difficult time figuring out what would be next when his career ended, like a lot of athletes. But he also had an extra, unfair burden; a lot of players go into coaching after their playing, but there weren’t very many schools or teams back then that were going to hire a gay Black coach…

He’s able to enjoy life for a very brief period in the Castro, after baseball, where he’s a softball star and still can identify as an athlete; I think his self-esteem was always tied up in his athleticism. But then he has the bad luck of being hit by a car and losing that part of his life, which is a huge blow to him. And then there’s the bad timing of having the dreamland of San Francisco turning into a hellscape with AIDS coming in… and then there’s the other sort of universal story of “What have you done for me lately?” When he’s no longer even a softball star, let alone a major league star, and can’t really do anything to benefit other people who may have been taking advantage of those skills, they drop him fast. The same people that he had treated to a lot of parties and perks and things like that, are unwilling to offer him a helping hand when he needs it. And so that’s really tragic.

Ultimately, what do you hope that a reader will take away from your book?

First of all, I hope they take away an interesting story about an interesting person. The second thing, which is a common theme across all three of my books, is understanding the difference between the way you think about something and what you actually do. Perry Wallace said the most difficult part of his own experience was being surrounded by people who would say, “Well, I’m not the one that called Perry an N-word; I’m not the one that kicked him out of church; I’m not the one that threatened to kill him. I didn’t do anything!” And they didn’t do anything — they didn’t step up for their teammate or their classmate, either. And then the second book is about Nazi Germany, and of course there’s the Eli Weisel quote about neutrality always being on the side of the oppressor…

There’s still so much evidence of homophobia and hatred towards gay people, and I think that if people read this story and learn about Glenn’s life and empathize with him, hopefully it will cause them to act in a way that is supportive of gay people in general, as well as specific gay people that are in their life. I hope that they’ll see the hypocrisy that we’ve talked a lot about in this interview, and will be more attuned to seeing that in the future. Also, I loved the quote from David Perry when he was inducting Glenn into the Rainbow Honor Walk outside the White Horse Inn in Oakland, where he said that gay heroes and heroines are all around us, even at home plate. So it’s important for me that sports fans understand that there are LGBTQ players, and that it’s kind of up to all of us to create an atmosphere where they feel comfortable enough to come out and be themselves so that they can pursue their dream. And I think we all benefit from that.

Singled Out: The True Story of Glenn Burke is out now, available in bookstores and online retailers everywhere.